The last time Rhys Herbert performed to a crowd at the Royal Albert Hall, he was nine. ‘It was for something called “raps and gaps”,’ he says, 14 years later. ‘All the schools in the borough were competing against each other.’

These days, Rhys is competing against major pop personalities rather than local schools. Known to most people as Digga D, he’s celebrated as one of the pioneers of UK drill; his hoppy flow and clever, ear-worm lyrics landing him millions of fans from all over the world. He’s released multiple top 10 tracks, been the subject of a BAFTA award-winning documentary and put out a mixtape which reached number one in the album charts, beating the likes of Ed Sheeran and Olivia Rodrigo.

But he’s also a controversial figure. Rhys has been in and out of prison and has a Criminal Behaviour Order (CBO), restricting who he can see and where he can go. It means he’s not allowed to talk about certain subjects in public and that his solicitor, Cecilia Goodwin, has to dial in on Zoom during this interview (she never interrupts). Rhys is the first person to have a CBO which controls his musical output: he’s even required to submit lyrics to the Metropolitan Police within 24 hours of release. It’s like walking on eggshells: every day, every hour, every bar.

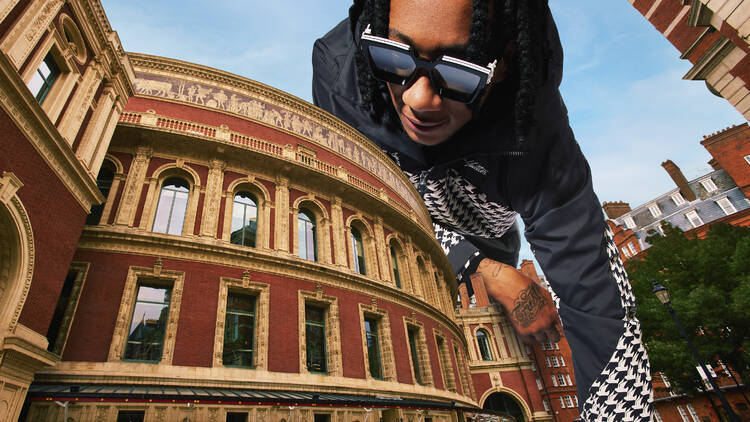

I meet Rhys two weeks before his big gig, on a warm October afternoon, inside the Royal Albert Hall. It’s rare to see the hall like this: silent apart from workers setting up the stage and the occasional chatter from tour guides. When you walk in, there’s a sense of awe about the space – its vastness only amplified by being empty – that feels almost holy. Under the dizzying domed ceiling, a shiny monument of an organ towers above the stage like an altarpiece.

Rhys is slouched in one of the stalls wearing white-rimmed shades, his thumb stuck in a robotic swiping motion on his phone screen, our photographer’s camera flashing continually. He’s quiet but impatient, keen to move onto the next pose. The next pose swiftly turns into the next location, then the next outfit, then the next job, as he hurries the team along with a sense of urgency. There’s no time to chill in Digga’s world.

Growing up west

When I speak to Rhys after the shoot, he’s tired and visibly run down. His nose is running and he’s been sneezing and spluttering all day. ‘I’ve been up and out since 9 o’clock,’ he says. This morning, he was at his old youth club, the Harrow Club, trying to visit the studio where he first started making music as a teenager. ‘They’ve made a new one; the older one is closed,’ he says. ‘I’m going to try and reopen it myself.’

Rhys says that the club hasn’t changed much otherwise. ‘Funnily enough, around this time ten years ago, we probably would have been getting ready to go to Thorpe Park for Halloween,’ he says. Statistically, you could argue it’s lucky that Harrow is open at all. From nearly 300 youth centres open across London in 2011, more than 130 had closed by 2021, with the average number of full time youth workers employed by a London council falling from 48 to just 15. New research this April found that a third of this city’s youth centres are now at risk of closure.

Rhys has previously voiced his support for London’s youth clubs, but maybe not for reasons you’d expect. ‘You know what it is?’ he says, animated. ‘Everyone’s on their phones. Before, you’d see children outside, enjoying nature on their pedal bikes. There are no teenagers outside enjoying life now, they’re all on TikTok. Socialising as humans is good and should be happening, but the next generation is changing.’

Rhys describes himself as a TikTok addict, but he wouldn’t ban the app if he could. ‘It’s about balance,’ he says. ‘I was addicted to PS3, playing Call of Duty and all those games after school all the time.’ I ask what side of TikTok he’s on and he pulls up his phone. The usual car crash of audio blares: bouncy pop, a video of a woman asking a man to hand back her stolen phone on the tube, a cat video. ‘I get a lot of wildlife videos,’ he says. ‘[But] I’m on the Jamaican side.’

Rhys grew up in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, born to a Bajan father and a Jamaican mother. He spent his childhood going to Sunday school, begging his mother for a dog (he’s had three in his time) and attending Notting Hill Carnival every August. ‘When I was super young and went with my parents, I used to hate standing up for so many hours, listening to the music blaring,’ he says. ‘The older I got, the more I enjoyed it. I last went when I was 15.’ Eighty-five percent of the music he listens to these days is Jamaican or Jamaican-inspired. ‘I made a five-track EP with only dancehall on there,’ he says. ‘It’s not out yet. I used to always have a dancehall song on each of my projects, but on my last one I didn’t. All my fans were like: ‘‘what’s going on?’’’

Digga has some serious fans. ‘I talk to most of them, answer their messages, give them advice,’ he says, explaining he has a ‘little spam page’ for those hardcore supporters. But despite his massive following, multi-thousand-pound designer jackets and gleaming Rolls Royce, he insists his relationship with London remains the same. ‘Everyone thinks I’ve changed,’ Rhys says. ‘I haven’t changed one bit. People see me queuing up in town and they’re like “yo Digga, what you doing?” I’m like, mate. I’m gonna be in Mcdonald’s, I’m gonna still be getting 50p things, picking pennies up from the ground. I don’t care. That’s the thing with London that I don’t like. People think that because you’re famous you should be different.’

Down with drill

In November 2017, Digga’s west London rap collective, 1011, named after their W10 and W11 postcodes (and later renamed CGM), released a video of themselves rapping ‘Next Up’ – a song which Rhys is now banned from performing in public. Less than a year later and a few days before his 18th birthday, he received ten months detention and a training order in a young offender institution for offences which occured in November 2017: violent disorder and possession of an offensive weapon. 1011 was identified by the Met police as a criminal gang and members were given sentences after allegedly travelling to attack a rival group. In the years that followed, media hysteria and moral panic enveloped UK drill music. To its critics, it celebrated gang violence, misogyny and crime. To its young fan base, however, it was the most exciting thing they’d ever heard.

As part of his sentence, Rhys was given a CBO. It’s a modern version of the ASBO, a piece of anti-antisocial behaviour law which can be issued by the courts. ‘The CBO, in essence, focuses on his musical outlet: what he can say in songs and in the public sphere, and also who he can and can’t be with in that context, in public,’ Cecilia says to me, the day after our photoshoot. ‘He can’t include things in his songs or anything published to the public, including interviews and live performances that encourage or incite violence. That could be anything, so he has to be extra careful with what he says and what he sings about. A breach means prison.’

Removal requests for UK drill TikTok content from the Met have increased by 366 percent over the last three years

Rhys was sentenced for violent disorder and four breaches of the CBO which had occurred in 2018 and 2019, and was released from prison in 2020. He is determined not to go back. His CBO is set to lift in 2025, when he’ll be able to live like a normal human being again (or as normal as a 23-year-old, famous rapper can). But for now, it continues to restrict his creative output and activities.

In the meantime, drill music as a genre is never far from the headlines. Only last week, DJ Mag reported that removal requests for UK drill TikTok content from the Met have increased by 366 percent over the last three years – accounting for 64 percent of all removal referrals on the platform in 2022/23. Meanwhile, drill lyrics are increasingly being used as evidence for trials in court, despite the Crown Prosecution Service saying it would review how rap evidence can be used in January last year. Critics see it all as part of a wider attack on young Black men from a certain demographic, in line with stop and searches and disproportionate custodial sentences. ‘It’s almost like some of these young people are just being set up to fail,’ Cecilia says. ‘The actual terms [of the CBO] really infiltrate a person’s whole life. But Rhys is very resilient.’

Going for the grind

‘I don’t like drill no more, it’s tired,’ spits Digga on ‘Fuck Drill’, one of the tracks on his most recent mixtape, ‘Back to Square One’, which he released in August on his label Black Money Records.

The attempt to distance himself from the genre – and possibly his teenage self – is obvious. The record is a departure from his previous sound: the tempo slower, the style more commercial, the lyrics exploring wider topics like fame, relationships and his faith. I find it more introspective, more vulnerable. ‘I can understand what you’re saying,’ he says, when I tell him. ‘But I don’t feel like I’m vulnerable in any of my music. More open, maybe. You can’t rap about the same things all the time. [Need to] tap into your other side.’

I ask Rhys if releasing the new mixtape is up there with his proudest moments of the year: he says no. (What was it? ‘Buying another house.’) ‘You know what it is,’ he says. ‘It’s work. How can you be proud of yourself for work? I’ll be proud of myself when I make 100 mil. People like to praise themselves for just doing the norm.’

If ‘Back to Square One’ was a head-strong attempt to locate Digga’s new big sound, his single, ‘TLC’, released at the start of this month, is a plea for a day off. It harks back to late nineties and early noughties hip hop, sampling Dr Dre’s classic ‘Xxplosive’ beat. ‘After the mixtape, I was like, I’m tired now, I wanna chill out,’ Rhys says. ‘Tender. Loving. Care. Literally: I need a massage, I need a facial, I need a foot rub.’ He doesn’t seem like the type of guy to spend too long winding down, but he assures me that after this show, he’s going to ‘book a spa week’. ‘It’s only recently I’ve been watching Netflix, because I’ve been working so hard,’ he says. I ask what he’s been watching. ‘YOU’ is very interesting.’

It might not be long until we see Rhys on the streaming platform himself: he later hints he’s already dipped his toes into the world of acting, and afterwards spills in a Capital Xtra interview that we’ll ‘see it on Netflix’. ‘I can’t tell ya,’ he laughs, when I ask for more info. ‘NDAs.’

Screen time

Rhys is no stranger to the screen: ‘Defending Digga D’ aired on BBC Three in 2020, following the rapper as he tried to navigate his career after being released from prison. Since then, he’s directed a music video for fellow UK drill star Unknown T, and also has a new, unreleased documentary under his belt – ‘11 Steps Forward, Ten Steps Back’ – looking ahead to the next stage of his life. It feels more raw, more future-facing, and in some ways, more optimistic.

I need a massage, I need a facial, I need a foot rub

A camera guy is with Rhys today, filming his movements with a clunky old-school VHS. I ask Rhys how important it is for him to be able to tell his own story, his own truth: he doesn’t take the bait.

‘It’s not important,’ he says.

‘So why do you do it?’

‘I just do it. It’s not important. Nothing is important – my family is important to me. I don’t know. You know what it is? I’m tired.’

Centre stage

According to Rhys, his closest friends would describe him as ‘a grumpy go-getter.’ He laughs and repeats it, savouring each syllable. ‘The perfect way to describe me,’ he says. ‘They say I’m grumpy, but then they see I’m always working.’

It’s that determination to keep making moves in spite of the CBO that means Digga will be the same age that Adele and Elton John were when they first headlined the Royal Albert Hall. I tell him he’ll be younger than Jimi Hendrix, who was 24, and Wizkid, who was 27. ‘Yes, that’s banging,’ he says, sneaking in a smile.

The details of the show still need refined: rehearsals haven’t kicked into gear yet and it’s not been decided if there will be support. ‘I’m feeling sceptical,’ Rhys says. ‘I don’t know if I’m using that word in the right way – but I’m not nervous. I just don’t know how it’s gonna turn out.’ I press him to tell me more about his vision: there’s talk of doing a string section and the venue website says he’ll be hosting a workshop tailored for young musicians before the performance. ‘I just want it to go good, I want everyone to sing along,’ he says, impatiently. He pauses, making a popping noise with his cheek. Then he looks at me, as though desperate to change the subject.

I’ve learned to take everything with a tablespoon of salt: a lot of people like to say “pinch”

‘Tell me about Scotland then, how about that?’ he says, referencing my accent. ‘How come we can’t – actually we can – use your money? I might actually have some Scottish notes on me now.’ (After the interview he proceeds to show me a huge wad of £20 notes, peeling them back to flash the Scottish ones.)

‘It’s a nightmare,’ I say. ‘Most of the shops here, even off-licences, won’t accept it.’

‘It’s real money, just looks different,’ Rhys continues at pace. ‘I force them to accept it, because how dare you tell me you can’t accept it?’

I nod. ‘Big up my Scottish people, man. Accept her money!’

God’s plan

I try to imagine Rhys as a nine year old, when he last performed here. He was around that age in the now-viral video of him meeting Nicki Minaj, half her height and giddy. It’s been a bit of a journey since then: he’s gone from DIY teen drill star to making controversial media headlines to big time rapper with his sights set on the mainstream. He says he wouldn’t change anything.

‘Imagine if you’d done things different?’ he says. ‘You have to make mistakes to learn. I’ve learned to take everything with a tablespoon of salt. A lot of people like to say “pinch”.’ Why, I ask? ‘Just remember that one. Always think everyone is doing you fake unless they prove that they’re real.’ What about his future self – would he tell them anything, if he could? ‘Nah,’ he says. ‘I’m a God-fearing man. It’s all in God’s hands, in God’s plan. What will be, will be.’

Digga D is playing the Royal Albert Hall on October 23. Find out more and buy tickets here.

Stylist: Nayaab Tania @nayaabtania @9inety6ixagency

Grooming: Flo Riff @floriffofficial @byriff

Location: Royal Albert Hall @royalalberthall

Look 1: @proletareart jeans and jacket, @celine shirt @amiri shoes and @bottega sunglasses at @mrporter

Look 2: @louisvuitton jacket, @acnestudios shirt, @jeaniusbaratelier and @louisvuitton sunglasses.

Look 3: @louisvuitton jacket and sunglasses, @mrporter turtleneck @1amicci pants and @dior trainers