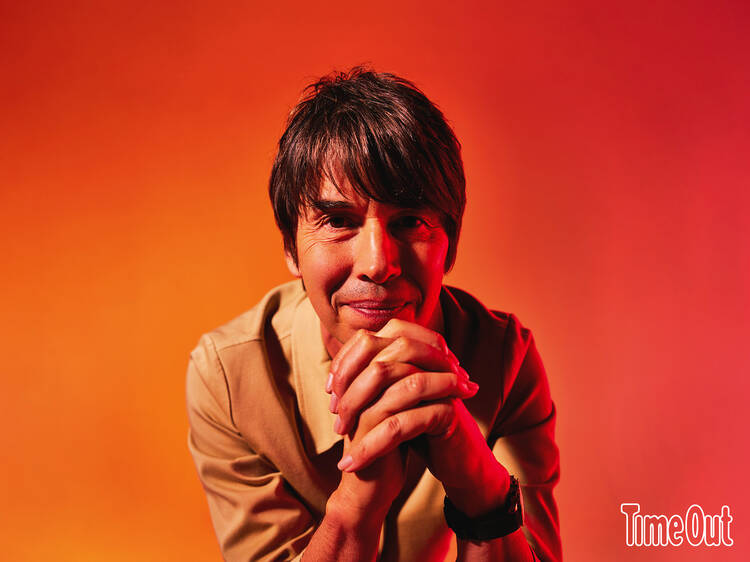

Professor Brian Cox is a man of big words and bigger questions. What is our place in the universe? What are we doing here? What does it all mean? They’re the kind of questions you’ll probably struggle to answer with words alone – and part of the reason why Cox is tackling them with an 86-strong symphony orchestra and huge LED screens in one of the most iconic arts venues in the country.

Teaming up with conductor Daniel Harding, ‘Symphonic Horizons’ is set to be a science-meets-music extravaganza at the Royal Opera House, interspersing the likes of Richard Strauss’s ‘Also sprach Zarathustra’ with Cox’s mind-melting musings. ‘I start the show by saying: what does it mean to live a finite, fragile life in an infinite, eternal universe?’ he says. ‘Nobody knows the answer. I strongly believe that music – and for that matter, literature and the arts – are all sorts of different lights you can shine on the same problem of existence.’

Of course, Cox is no stranger to the stage – even if, thanks to his earlier musical career as D:Ream’s former keys player, he’s still more closely associated with nineties dance-pop than German classical. Now living between south London and Manchester University, where he lectures first year students on particle physics, Cox has also built a career in broadcasting, presenting science programmes like the BBC’s The Infinite Monkey Cage and The Planets. As he looks forward to his ROH spectacular next month, he speaks to Time Out about the big (and small) ideas.

Tell me more about the show – it sounds very exciting.

We first did it at the Sydney Opera House with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra back in December. It was beyond my expectations, really. You can’t imagine it until you’re in the auditorium with all those musicians and the conductor and the big LED screens.

The Royal Opera House is built for this music, these ideas and visuals. We’ve got a premiere of a piece by Hans Zimmer – we’ve sort of developed it together. That’s being played for the first time.

What is the difference between sound and music? Is there a scientific explanation?

Music is organised sound. There’s certainly a mathematical element to it in terms of the frequencies of notes. But, as Mahler said, music is the language that’s able to express things with a level of complexity and depth that language can’t.

You’ve had quite a unique experience in that you’ve had a career in music and the arts, but also in science and academia. Do you think they’re just as important? Is one more deserving of funding than the other?

I don’t see these chutes as separate. Ultimately, we have to ask the question: what are we doing here as individuals? The boundaries blur away. I don’t see the difference between trying to understand why grass is green and trying to express the immensity of the universe through music. Separating the educational experience out into different silos just doesn’t make any sense to me. How do you say that Newton’s Principia Mathematica is more valuable than Shakespeare? I think it’s a fundamental misunderstanding of the purpose of education, which is to allow each individual human being to grow.

After hearing more about the themes in your show, I’m astounded you don’t get caught up in the existentialism of it all. What do you do to ground your sense of reality on the day-to-day?

I don’t! The answer to that question is that we don’t actually know what reality is. Through the study of black holes, we’re beginning to suspect that space and time emerge out of something deeper that doesn’t have space and time in it. When someone says you should be grounded in reality, my instant reaction is: ‘Well, tell me what it is then.’

What does it mean to live these finite fragile lives in an infinite eternal universe?

On theme of existentialism – for younger people, there’s this sense of looming doom at the moment about climate change. What is the worst case scenario for the entire universe if the Earth was to end?

This is one of the central themes of the second half of my show: what it means to live these finite fragile lives in an infinite eternal universe. The immediate reaction is to just feel insignificant. Talking about the size or scale of the universe, we are physically insignificant. But my guess, as many of my colleagues would guess the same, is that there are very few civilizations in a typical galaxy.

So it’s just us?

One guess is it’s just us. It took four billion years on this planet to go from cell to civilisation. A third of the age of the universe. This planet, this little shell of atmosphere, and these little fragile oceans, managed to avoid the fate of virtually everything else in the universe – supernova explosions and impact from space. If this is the only place where intelligent life currently exists in the Milky Way, then it would be a tragedy beyond belief if we eliminated ourselves.

Are you going to be playing any keys in the show?

I’m not good enough for that. There is an organ, but there’s no way that I can do that!

Fair enough. I have to ask – after the clip of Rishi making the big announcement the other week – what was it like when D:Ream’s ‘Things Can Only Get Better’ became the anthem of the 1997 election? Can you take me back to that time?

Oh, it was wonderful at the time. Everybody had a tremendous sense of optimism. It was written in ’92, ’93 and has become the ultimate protest song. It’s a celebration of what might be. I know that the band themselves, Peter and Al, don’t really like the political connotations – don’t they say that all political careers end in failure? So if you have a song that becomes so closely associated with a particular government, then it loses its universal meaning.

If Starmer does win, what song would you choose to be the new soundtrack?

You could do Strauss’s ‘The Song of the Night Wanderer’. There’s this argument all the way through it about humans’ basic nature of trying to understand our place in the universe. At the end, it’s unresolved. It’s so strange. The music just disappears in an unresolved argument. Maybe that’s the appropriate soundtrack.

I’ll have to go and listen.

The whole of Strauss’s Zarathustra is about 26, 28 minutes long. It’s wonderful when you know a bit about it: basically, Zarathustra, in search for the meaning of life, goes into the woods and meets a saint. Then he rejects it: religion is not the answer. Then he tries science and learning. He rejects that. Then he tries partying: there’s this waltz that goes out of control. And he rejects that. He find the answer is a synthesis of all of them. I suppose maybe that’s what politics in a country like ours is. It’s brilliant as a piece of music, as a journey.

Have you got any other TV things in the works?

We’ve just finished a new series, a sequel to The Planets, called Solar System. We haven’t got a date yet. It’ll be autumn sometime.

You sound very busy. Will you be tempted to join your old bandmates at Glastonbury?

I’m tempted… I will be there, recording The Infinite Monkey Cage and chatting with Youth, the great musician and music producer.

If there is another London, we would never have any chance of contacting it – so we have to be satisfied with our London

We always refer to pop stars; our critics give out star ratings. What’s the scientific explanation of what a star is? Why are people so drawn to them?

I remember Carl Sagan saying that the moment that changed his life was when you realise that stars are not just points of light in the sky: they’re suns, solar systems and planets. They’re a magical sight even if we don’t know what they are. I suppose it’s just the immense challenge of existence.

All comes down to existence, it seems. Could another London exist?

Another London?

Yeah. Like in a parallel universe?

Well, even in our universe: our universe might be infinite. We know it’s a lot bigger than the bit we can see – which has got a million galaxies in it, by the way. That’s before we get to multiverses. The one thing to say is, if there is another London, it would be so far away that we would never have any chance of contacting it. So we have to be satisfied with our London.

Do you have a favourite gig venue in London?

The first time I ever played in London was at Hammersmith [Eventim Apollo], with my band supporting Jimmy Page in 1988. We’ve done The Marquee, which was a great club. And we did the Astoria which is not there anymore. So I have those happy memories of the ’80s and ’90s through some of the great rock and roll peaks.

And what do you hope audiences get out of your Royal Opera House show if they come away with one thing?

That existence is fragile and precious. Our place in the universe is that we’re simultaneously physically insignificant and fragile, and unimaginably valuable at the same time.

Professor Brian Cox and Daniel Harding: Symphonic Horizons is at the Royal Opera House, July 30-August 4.