This review is from 2016. 'Akhnaten' returns to ENO in February 2019.

In Pharaohic terms, 17 years is but a blink of a kohl-lined eye, but Akhnaten (hubby of Nefertiti, daddy of Tutankhamun) ensured a kind of immortality during his short reign by doing away with the whole multi-god thing and replacing it with worship of a single deity: the sun-disc, or Aten.

Did he learn to juggle, too? That’s the question you may ask yourself during this new production of Philip Glass’s 1983 opera, directed by Phelim McDermot. Courtesy of members of Gandini Juggling, balls fly through the air in ever more complex patterns – growing in size from juggling balls to beach balls (symbols of the sun) as Akhnaten’s encounter with his solar deity draws near. Even the chorus gets involved, as if singing in Egyptian, Hebrew and Akkadian wasn’t difficult enough. Such is the production’s commitment to ball control, you half expect the pharaoh himself to engage in a spot of keepy-uppy during his extended moment in the sun.

The Cirque-like tricks serve a purpose beyond keeping you visually entertained. They underscore the insistence of Glass’s music, as well acting as a kind of counterpoint to its complex cross-rhythms. Which isn’t to say that the music is especially challenging to listen to. Glass has always been the minimalist composer with the catchiest tunes, and ‘Akhnaten’ has the most hauntingly beautiful songs of his ‘Trilogy’, notably the pharaoh’s doleful ‘Hymn to the Sun’.

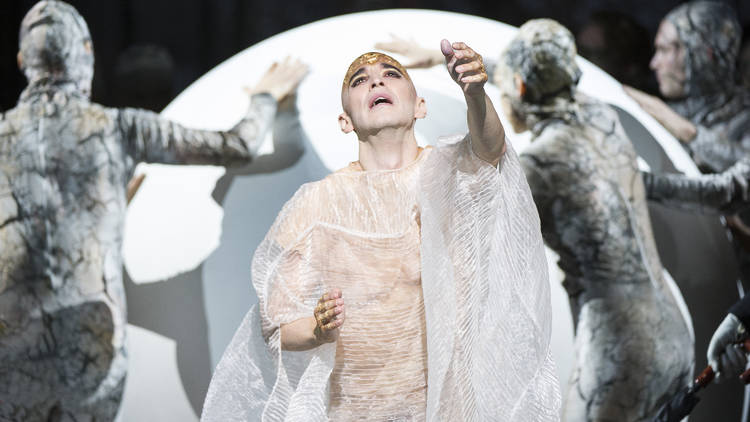

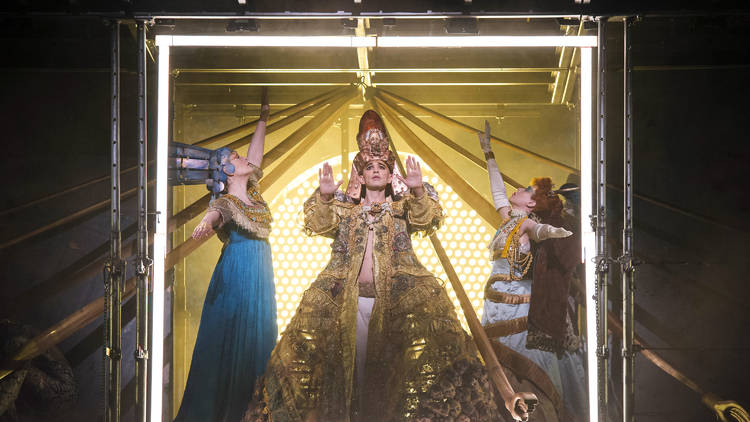

From the first moment he’s manhandled, naked, into his coronation britches, countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo’s Akhnaten brings a touching vulnerability to his portrayal of a man with a plan that, palpably, is not going down well with the people around him. Rebecca Bottone as his mum, the brittle matriarch Queen Tye, commands the stage even when her role confines her to following people about, slowly. Emma Carrington’s Nefertiti, by contrast, radiates sensuality, bringing a richness to the duets that only once or twice threatens to overpower the reedier tone of her diminutive spouse.

The first act is confined to a shallow, three-storey structure at the front of the stage, lending the action a frieze-like feel that’s obviously indebted to Ancient Egypt. It also serves to accentuate the claustrophobia of Glass’s repetitive score, handled best under conductor Karen Kamensek during the agitated pomp of Akhnaten’s father’s funeral and the fiendish, full throttle, not-quite-finale ‘Attack and Fall’.

Tom Pye’s clever set takes you from the flat world of the hieroglyph to sun-filled space and back again, while Kevin Pollard’s opulent fashion-forward costumes nod to the land of the pharaohs without descending into cliché. But, fittingly, it’s the beautifully observed lighting, designed by the aptly named Bruno Poet, that lifts the production, making this extended homage to the sun truly transcendent.