‘Ah, the Silk Road!’ you nod, sagely. That romanticised overland route between Asia and Europe that flourished in the Middle Ages as intrepid Chinese merchants took silk over the arduous routes in the West. Camels! Deserts! Caravans! Marco Polo!

In fact, as with much of history, ‘the silk road’ was somewhat made up in retrospect to describe a less tangible phenomenon.

The British Museum’s new exhibition Silk Roads contains little in the way of first person accounts of adventurous journeys from one end of the world to the other, because a few intrepid explorers aside, this simply wasn’t a thing that happened. Instead the silk road of myth was the sum of myriad trading networks – of everything, not just silk – between Japan, north-east Europe and West Africa.

Was the sixth century bronze Buddha unearthed on the Swedish island of Helgo in 1958 directly traded there by a wandering salesman from present day Pakistan, where it was forged? Probably not, but the two were sufficiently interlinked by trade that its presence is perfectly explicable. Camels were involved at times, but so, more prosaically, were boats – some of the best preserved items in the exhibition are mass produced Chinese crockery made for the export market, retrieved from an ancient shipwreck in 1998.

What Silk Roads is great at is conjuring an image of a Dark Ages that was far from dark, a teeming, interconnected world in which cultures were shaped by nascent religions – Buddhism, Islam, Daoism, weird offshoots of Christianity. An age in which world was dreamt up anew, and civilisations traded with their neighbours, who traded with their neighbours and so on, until theoretically goods could travel from, say, the Tang capital of Chang’an to Litchfield.

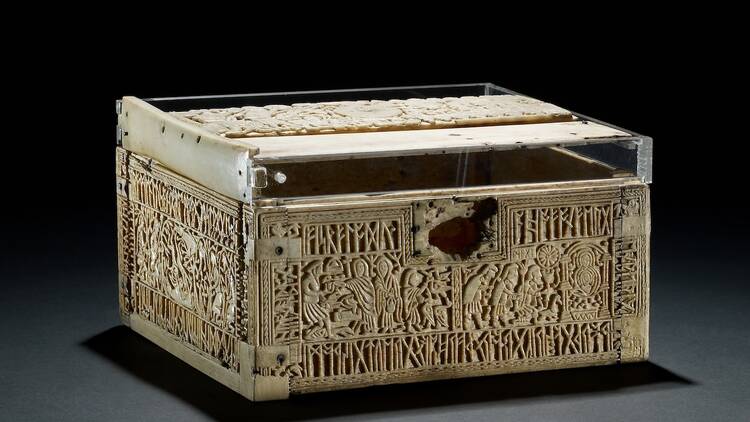

Starting in Japan and finishing up in north west Europe, with stops everywhere from Constantinople to the Kingdom of Ghana, the exhibition is itself a loosely East to West journey. There aren’t really a lot of show stopping items on display – millennia-old silk is basically hard and brown – but the various artefacts relative to each waypoint on the ‘road’ build up convincing evidence of a Europe, Asia, Africa and Middle East of distinct, disparate but palpably interlinked countries, many long gone, not just trading from each other but learning too.

There’s an element of fudging here, with different civilisations represented by quite different centuries – the vision of a seamless, coherent world it sells us is perhaps a little telescoped, a tiny bit too eager to counteract Dark Ages clichés.

But in the end Silk Roads is magical less for the evidence of connectedness than the sheer abundance of documentation of civilization it provides. Yes, we have our stereotypes about the Middle Ages, and yes, they tend be western centric. But it’s not unreasonable to not be an expert on every country that flourished between here and Japan in the second half of the first millennium. Silk Roads won’t turn you into an expert, but it does briefly shine an intoxicating light on this vast, unfamiliar and endlessly vibrant world.