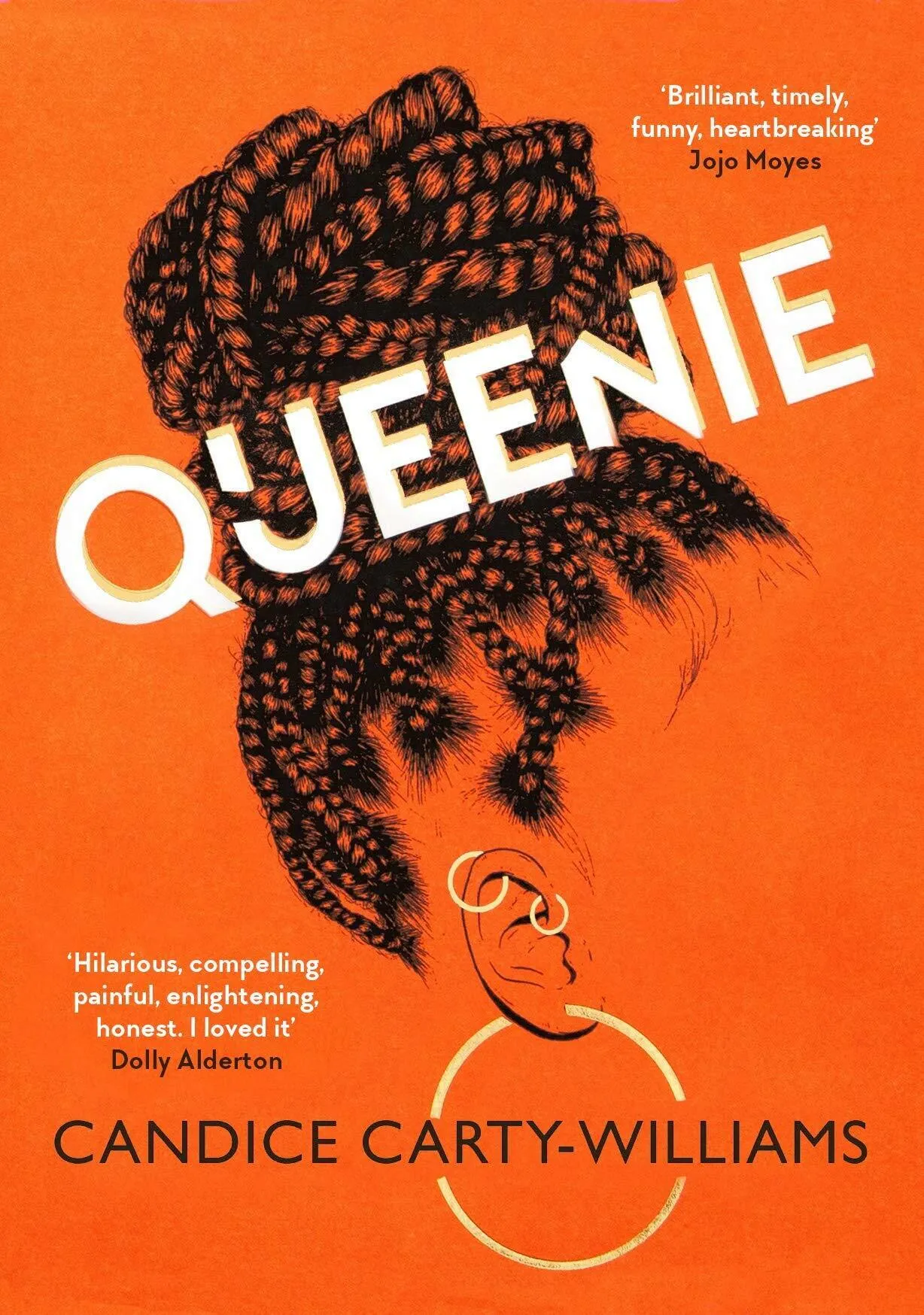

Bestselling author, journalist and now TV showrunner, Candice Carty-Williams answers to a few descriptions. But the label she loves most is that of proud South Londoner. Having grown up in Lewisham and bobbed between Croydon, Streatham and Clapham in her 20s and early 30s, she knows the best spots south of the river for film (Peckhamplex), theatre (Brixton House), a manicure (Luna and Wilde), and oxtail (Cool Breeze, Hither Green’s Caribbean takeaway). And of course, she’s written two 100,000-word love letters to the area: her 2019 debut novel ‘Queenie’, now an eagerly anticipated telly series, and its follow up, 2022’s ‘People Person’.

Chatting from her car on a gloomy Thursday afternoon, she mentions that she’s considered giving Lambeth the Marvel treatment. ‘I always think about combining my worlds. Maybe I’ll create the “CCW multiverse”.’

Right now, we’re entering phase 1. ‘Queenie’, which won Book of the Year in 2020, is now an eight-part Channel 4 series, stars Dionne Brown as Queenie Jenkins, a 25-year-old social media assistant, as she navigates heartbreak, mental health, racism, and the suffocating love of her family – as well as the horrors of damp flatshares and the sensory mindfield that is Brixton Road.

What makes Queenie a relatable Londoner?

She loves South London. In the book and the TV series, she’s always walking around and feels safe – it’s never scary, or weird, or uninhabitable. She’s really proud of the South London she grew up in, and she’s devastated to see it change for the worse. She’s also somebody who is making mistakes. I wanted people to see somebody who doesn't have it all together.

We first meet Queenie at a gynaecologist appointment where she undergoes an internal examination. Why did you choose to introduce her in that way?

We’re ambushed by the myth of the strong Black woman. It’s always plagued me. I wanted to start this novel and the TV series with Queenie in the stirrups because it is the most vulnerable place you can find a woman. I wanted people to see her immediately as a vulnerable person so they could connect with her.

There's also an intersection of hypervisibility and invisibility of the Black woman – and it’s never decided by us, but for us. It was really important for me to show that in those situations where you're meant to be taken care of, sometimes you’re not seen or heard. Sometimes [medical professionals] won’t even remember your name.

You’ve spoken about Queenie being ‘the Black Bridget Jones’. Can you tell us a bit more about that?

Black Bridget Jones was my comparison for scale. I want Queenie to be as spoken about and as recognised and understood as Bridget Jones. I want Queenie to be in people's houses. I want nieces to be stealing my book from their aunties’ shelves.

Heartbreak is a big theme in the book. What advice would you give to anyone going through it?

Don’t let someone have access to you when they don’t deserve it. I know heartbreak well and the thing that makes me feel better is walking. I don't take music or anything, I just like to move forward to get my head straight. I love Ruskin Park (in Denmark Hill) because it has a Tree Trail you can follow. I’m a proper nerd for that sort of thing.

View this post on Instagram

Stereotypes of the ‘angry Black woman’ are also covered in the show. What impact does this trope have on Queenie and Black women more generally?

It’s difficult when you’re labelled as the angry Black woman because people are able to kind of dismiss your thoughts and feelings. It shifts everything onto us, like we’re generating our own problems. But anger doesn’t come from nowhere. I've spent a lot of time making my anger smaller, swallowing it and letting it sort of beat me up from the inside because I don't want to be called an angry Black woman.

The Corgis group chat is a prominent part of the book and show. How important are these digital spaces in modern friendships?

It’s unrealistic to show four women who find time to constantly be together. This isn’t ‘Sex and the City’. The group chat is shorthand and where a lot of women find moral support. It's one of my favourite spaces. When I was dating a personal trainer my friends nicknamed him ‘Captain Cardio’. I couldn't ever be like I'm sad about this person or this thing that he did because I was laughing too much.

I wrote the family I really would have liked to have had

Queenie’s Jamaican identity is central in the show. What did you want to show about her heritage specifically?

There’s a cleanliness that Jamicans have. And there are so many reasons for that. My nan was always obsessed with being clean. It wasn't because she thought it was nice to be clean. It was more a case of if you get ill, I'll have to take you to hospital and I don't know how they're going to treat you in the hospital because we're different from them. That’s been passed down generationally as a form of protection.

Also the lack of boundaries. Aunt Maggie is bullish. Even though it’s never said you know she’s invited herself to Queenie’s medical appointment. I wanted to show how this overbearingness is a form of love.

How did you go about choosing the music for ‘Queenie’?

It’s music I love. We included ‘Wait a Minute’ by (Nigerian-British rapper) Ty, who passed away from pneumonia during the Covid pandemic. He was a huge part of the south London music scene so I wanted to honour him. We also have ‘Playground’ by Fundamental. One of the writers had changed his name so it took us about two months to track him down. He let us use the song because he was impressed we found him. But the score for me is probably my favourite thing about the show. It kind of says everything that needs to be said.

Queenie has a lovely relationship with her grandfather. Was he inspired by any of the paternal figures in your life?

My grandfather and father both worked on the Underground. They fixed signals, and I thought it was the most important job in the world. They were always getting their boots on and going down into the tunnel. My dad was always stationed at either Morden or Kennington. He was a man of few words so when I’d visit him at work we’d sit in his office watching telly until something went wrong with a train.

The relationship between Queenie and Grandad is the one I suppose I would have wanted with my granddad. When we were on set filming Queenie’s birthday party, I looked around and I realised I’d written the family that I really would have liked to have had.

What’s one thing that TV and film always gets wrong about London?

How long it takes to travel from one place to the other. ‘You’ was mental. Let's be realistic. Show that it would take seven hours to walk from A to B and it’ll be dark when they get there.

‘Queenie’ is streaming on Channel 4 in the UK and Hulu in the US now.