‘Everything about Jamie Laing beckons you to hate him! His hair transplant, his biscuit fortune…’

Jamie Laing is looking at a screenshot, reading out what he claims is the nicest compliment he’s ever received.

‘...his effortless transition to light entertainment, after seeming too “hoorah” for even Made in Chelsea. And yet…’

He holds up his phone, triumphantly: ‘And yet!’

You can probably guess how the rest of that goes. Because chances are, it’s how you feel about Jamie Laing. You may sneer and roll your eyes at people who look, talk and act like him, but you can’t bring yourself to dislike him. You might even actually like him. Because, to quote The Fence magazine (from which he’s reading):

‘Jamie Laing is a cunt,’ says Jamie Laing. ‘But a good cunt!’

The sweet spot

C-word or otherwise, we’ve come to meet the man at his office (inevitably named The Sweet Factory) near Baker Street. It’s from this cosy cobbled mews that he co-runs Candy Kittens (sweets) and JamPot (podcasts and whatnot). The team only moved in this year and Laing is excited to have a non-SW10 bit of London to explore.

‘I went to this restaurant around the corner called Lita,’ he says, rhapsodising about the new mediterranean joint Time Out had just awarded five stars. ‘I was like “Holy shit, this is good.” I got this fresh tuna thing. It was outrageous. Then there’s the family-run sandwich shop, Paul Rothe and Sons...’

With its cheerful colours, boutique-y furnishings and plenty of motivational slogans (‘Better Is Possible’), you might describe The Sweet Factory as Laing-core. Or maybe Willy Wonka’s WeWork. The TVs display tastefully designed reminders about the next team social (an ‘art gym workshop’) and the tongue-in-cheek ‘employee of the month’ posters in the loos all show Jamie’s perma-grinning face. His memoir I Can Explain sits on most of the office bookcases. Surely, I ask an employee privately, surely it all gets a bit annoying?

‘Genuinely no,’ they say. ‘Jamie’s a really kind guy. And he’s got such a lust for life, just being around him puts you in a good mood.’

Jamie Laing the celebrity was created by the noughties reality TV content factory. Initially it seemed like there wasn’t much distinguishing him from his west London co-stars on Made in Chelsea. However, as the years went by, something peculiar happened. The public warmed to him (as evinced by all of the heart-felt thank you letters from kids and adults plastered over his office). Unlike almost everyone who’s ever starred on a reality show, Laing somehow emerged with his credibility intact.

People will come up to me on the street and say ‘I really fucking hate you on the radio’

These days, Laing is famous for a few different things. He does a couple of podcasts (NewlyWeds with his wife and former MIC co-star Sophie Habboo; Great Company in which he natters away to interesting celebrities), is the face of the Candy Kittens empire (which surged into profitability in 2023 after sales jumped from £9.4 million to £12m in a year) and, since March, also fronts BBC Radio 1’s prestigious drive-time slot. The last one represents Laing’s biggest leap yet towards mainstream ubiquity. How does live radio compare to podcasting?

‘I love the fact that once it’s done it’s done,’ he says. ‘It’s history, it’s out there, you don’t have to worry about the edit. That’s magic. And the feedback you get, it’s more casual, more real. Not just people immediately leaving comments on YouTube.’

What do you mean by casual?

‘People will come up to me on the street and say “I really fucking hate you on the radio”.’

Laing’s self-awareness – an ability to absorb abuse – isn’t some kind of PR-friendly ruse. You could literally call him a posh twat to his face and I’m certain he’d laugh affably, ruffle your hair and send you away with pockets bulging with Candy Kittens.

But does it genuinely never get to him? People being rude about him?

‘My mother prepared me for a life of people being rude to me,’ he says. ‘She was incredibly rude about me. To my face! She always has been. I love her for it, for some reason.’

What’s the worst thing she’s ever said to him?

‘Apart from saying my hair looked like “ghastly bleached straw” the other day? Well, I asked her why she sent me to boarding school, and she just said outright she wanted her own life back. Fucking brutal.’

Laing’s upbringing – the poshness, the boarding school – is still his defining feature. People natter incessantly about the ‘McVities fortune’: a pile of riches, generated by the biscuit company which his grandfather founded. I ask him why people are so obsessed with it.

‘Well, I think it’s to do with heritage. And people are nostalgic for that stuff.’

And is he going to inherit a vast biscuit fortune?

‘No! It’s not true. It’s a shame because my grandfather, Alexander Grant, who created McVities, was an amazing person. He was a baker’s apprentice, and he built his way up from there. He also gave so much money to charity, anonymously. I think he donated a whole park to Scotland at one point.’

I get the stigma attached to being the heir to a fortune, but none of the money

It clearly irks Laing that all the philanthropy done by Grant (which is a lot, check his Wiki) is now overshadowed by a gossipy, squalid conversation about whether he’s going to inherit the millions (he assures me he isn’t, by the way).

‘I get the stigma attached to being the heir to a fortune,’ he says. ‘But none of the money.’

Then, realising he might sound self-pitying, he adds:

‘I mean, as far as boulders you have to carry around, the fact that people think I’m rich or posh, that’s an okay one to carry around in the grand scheme of things, isn’t it?’

Trick or treat

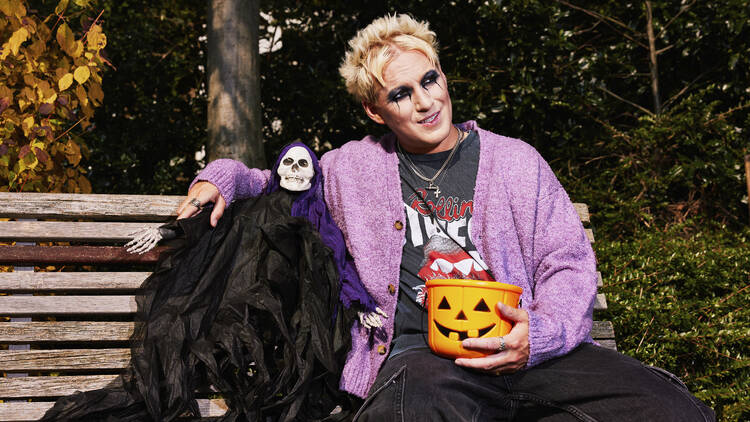

A week or so before the visit to The Sweet Factory, Jamie Laing is taking part in a spooky Time Out photoshoot for our Halloween cover. Cramming sweets into his mouth, snarling at the camera, he resembles an absurd cross between a goth’d up Kurt Cobain and Schooner Scorer. Photographer Jess is keen for Jamie to make scary or intimidating faces, but it soon turns out that this is simply something his face cannot do. Asking Jamie Laing to look scary is like asking a horse to swim gracefully.

Luckily, despite not looking the part, Laing does consider himself a committed fan of the horror film genre.

‘I’m not a gore guy,’ he explains. ‘Don’t like Saw. I like tension.’

He reels off a list of fairly obscure films that underline his credentials as a serious student of scary cinema, asking if I’d seen each of them with the seriousness of a doctor checking a patient for a list of symptoms.

‘Have you seen Speak No Evil?’ he asks. ‘The original, not the one with James McAvoy. The Danish version. Almost nothing happens throughout. But you’re terrified.’

Sounds good, I reply.

‘And Train to Busan,’ he adds, apparently unable to stop the torrent of recommendations. ‘And Talk To Me, the Australian one.’

Appropriately, Halloween is a particularly fruitful time for a candy tycoon. ‘It’s a big time for the sweet business,’ Laing says. ‘Candy Kittens are the only sweets you should be buying, by the way. Because not only are you buying the best tasting sweets, you’re also doing right by the planet.’

There should be bloody warnings on social media, like what you get with alcohol

What might sound like implausible corporate film-flam is actually factual. Candy Kittens became the UK’s first B Corp-certified sweets company, which basically means the business is sustainable, good for society and not pursuing profit at the expense of humanity. Which might sound weird for a company that sells sweets, but this is 2024. These days the bad guys peddle more… insidious wares.

‘I absolutely, 100 percent think social media is bad for society,’ he says later. ‘We’re meant to have around 100 people in our lives, what’s called the “village mentality”. But these days everyone knows 5,000 people.’

Does he think there should be…

‘Yes there should be,’ he says, cutting me off. ‘An age limit. There should be bloody warnings on this stuff, like what you get with alcohol and tobacco. I see it with my brother. He’s at university now, and he’ll go to the pub with his friends. But they also all spend a lot of time in their rooms, on TikTok. Which is a super claustrophobic space.’

It’s odd – and refreshing – to hear someone who makes a good living off of social media criticise the medium (after all, it’s hard to imagine the 2024 iteration of Jamie Laing without his fairly non-stop video output).

‘We’re meant to have USPs as humans,’ he says. ‘Something we feel like we’re especially good at. But with social media you wake up to thousands of people doing what you do, but apparently better. So we feel inadequate. That’s so awful for young people, in particular. To be constantly comparing yourself to others. Who needs that?’

Onwards and upwards

Laing is no stranger to inadequacy and feelings of worthlessness. He can thank his education for that.

‘At boarding school you’re never going home,’ he says. ‘You’re constantly surrounded by your peers. Twenty-four seven. And it was all men. Your currency in that world is either sport or academics. You have to be good at one of them. That’s what drove my competitiveness.’

If that sounds like he’s boasting, he isn’t. Laing’s grateful for having benefited from an expensive education but refers to sending a child to boarding school as ‘a mad thing to do to a person in 2024’.

‘I had a terrible time of it later,’ he says, referring to a period of his life where he suffered from extreme anxiety and panic attacks. ‘I took myself to hospital, as I genuinely thought I was dying. And after that, I felt like I was living in fear. I was scared about everything, constantly panicking that I was going to have another panic attack. It was awful.’

He blames too much drinking, a lack of self knowledge but also a brain that couldn’t accept failure. A brain that had been hardwired in the lonely corridors of British boarding school.

‘Eventually it became depersonalization, or disassociation,’ he says. ‘Which is where you basically go on autopilot and your body sort of separates itself. I’ve always had this competitive drive and it felt as if my brain was betraying me. It was really upsetting.’

Being famous on a reality television programme didn’t help matters. Laing has featured as himself in a stocking 212 episodes of Made In Chelsea and has spoken in the past about how emotionally disorientating – and genuinely damaging – such an experience can be.

‘I had no control over the edit, obviously,’ he says, flatly. ‘And I was being told what to do, as they had to make an entertainment show. In a sense I was being lied to.’

He’s not bitter about it. Laing clearly has an admiration for the people who craft addictive reality television, even if he can’t enjoy it anymore (‘I just know how it all works – it’s lost its sparkle’). Still, he clearly didn’t enjoy certain aspects of the experience.

‘It felt a bit like being trapped,’ he says. ‘They [the producers] weren’t nasty, but they’d just hold certain things back. Prevent you from having certain conversations.’

These days, Laing is a massive advocate for therapy as a way for people to get to know themselves better and overcome the various obstacles we create in our minds.

‘I realise I’m in a privileged place to be able to do therapy,’ he says. ‘But to me, self-awareness is absolutely everything. So many of us are born to be psychopaths, and it’s something you have to unlearn. And then in its place therapy can show you how to recognise and articulate your own feelings.’

Laing also credits therapy if you ask how he remains happily married to his wife while co-hosting a podcast and generally existing in the same pop culture space together.

Think how many marriages end in divorce? Therapy gives you a referee to help you navigate life together

‘Couples therapy,’ he says. ‘I’m being really open about that. Think how many marriages end in divorce. Why would you not want to set yourself up to protect against that? Therapy gives you a referee to help you both navigate life together. I think we’re all just broken souls trying to figure it all out, really.’

The idea of being broken, misshapen or ‘bumpy’ is something Laing comes back to again and again during our chat. But, even if he’s still trying to ‘figure it all out’, he at least looks like someone who has his shit together. Despite working in an environment where there are unlimited, free sweets almost everywhere, Laing’s lunch is an edifying but sad-looking pack of salmon and broccoli.

‘That’s my diet at the moment,’ he says glumly.

I ask what kind of diet he’s on.

‘Charm, empathy and kindness,’ he replies.

What does kindness taste like?

‘To me it tastes great,’ he says. ‘But for some people… I think it tastes bitter. Can you put that right at the end of the interview, so I sound really profound?’