[title]

The Rolling Stones show ‘Exhibitionism’ has just opened, putting ‘swinging’ London back in the spotlight. Kate Solomon revisits the decade’s hottest locations

Carnaby Street

Carnaby Street was just a grubby Piccadilly thoroughfare before ‘His Clothes’ opened in 1958 and ushered in the swinging ’60s. With its bright yellow sign and blaring pop music the menswear boutique drew hip young things like moths to an affordable (if not massively well-crafted) flame, and everyone from The Beatles to Sean Connery shopped there. Copycat shops flooded the street and with all the bands kicking their heels there it’s no wonder that the Carnaby phenomenon was immortalised in song: The Kinks’ ‘Dedicated Follower of Fashion’ pokes fun at the identikit mod hipsters who couldn’t get enough of it. God knows what they’d have made of The Kooples.

Today try: The Carnaby Echoes app. Take yourself on a tour of the area’s musical history. You can always pop into The Kooples while you’re there.

Bazaar, King's Road

Alamy

If Carnaby Street reinvented menswear, when it came to women’s fashion, Chelsea was the place to be. It was all thanks to Mary Quant, who, at just 21, opened Bazaar on King’s Road. Famous for its surreal window displays and a little thing called the miniskirt, it became a hotspot for London’s chic dolly birds. Quant didn’t know much about running a shop – she underpriced everything and constantly ran out of stock, working through the night to make clothes for the following day. But she gave swinging London its look, and her Peter Pan collars and ‘Boobly Trap’ bras were quite literally made in Chelsea.

Today try: What the Butler Wore on Lower Marsh - it specialises in vintage ’60s fashion and has rails bulging with shift dresses and leather jackets.

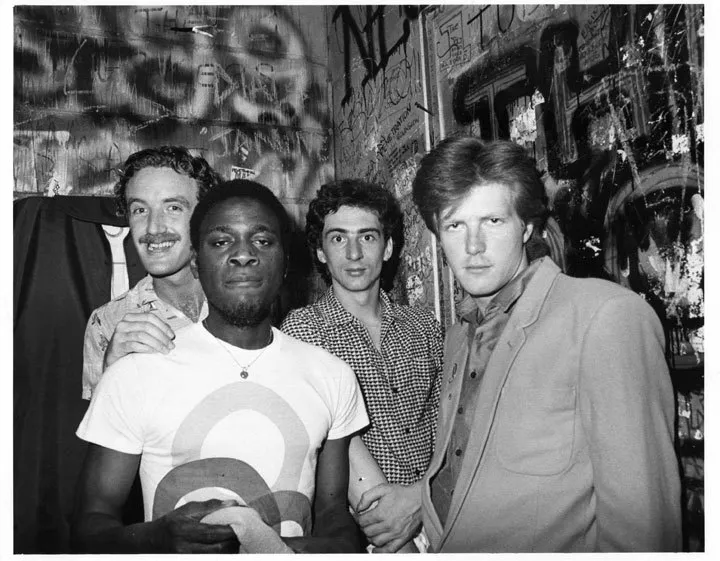

The Marquee Club

Shutterstock

Wardour Street was awash with teens in the ’60s because you would arrange to meet your friends outside the Marquee Club. When the venue moved there from Oxford Street in 1964, 600 people were turned away on opening night, and even more were left out in the cold when Jimi Hendrix played there in January 1967. The club was booze-free throughout the ’60s, though who can say what other substances were consumed there? The dressing-room graffiti was legendary, but the obscenities scrawled by The Who and others were lost forever when the building was demolished.

Today try: The 100 Club on Oxford Street has a similarly storied history and occasionally hosts secret shows by some of the world’s biggest acts.

Eel Pie Island Hotel

Mike Peters

Eel Pie Island Hotel was every west London parent’s worst nightmare, but walking over the bridge to this mid-Thames venue was to enter another world for Twickenham’s teens. As well as introducing them to Newcastle Brown and the joy of jiving on a sprung dancefloor, ‘Eelpiland’ played regular host to an eclectic mix of blues and jazz artists, including The Yardbirds, Rod ‘The Mod’ Stewart and The Who. The grounds also had plenty of greenery, ideal for getting, er, intimate in. It burned down in 1970 and Eel Pie Island is now a haven for artists.

Today try: The island is private but the artist studios, situated around a working boatyard, are open to visitors twice a year. The next dates are 25-26 June and 2-3 July.

Tin Pan Alley

PA Archive/Press Association

In the shadow of Centre Point lies Tin Pan Alley, a veritable hotbed of music history. Now reduced to a handful of guitar shops staving off Crossrail’s advances, Denmark Street (as it’s formally known) is where both the NME and Melody Maker were founded, and where young bands like The Rolling Stones went to buy instruments and lay down tracks at Regent Sounds, one of several small recording studios tucked away among the shops. La Gioconda was a favoured coffee bar hangout – by some accounts you couldn’t get one lad by the name of of David Jones (later Bowie) out of the legendary café. It’s now a steak restaurant, boasting a blue plaque with its former incarnation referred to as ‘La Giaconda’. Oh well...

Today try: Tin Pan Alley, while you still have the chance. The studios and publishers are mostly gone, and commercial pressures are forcing the last of the instrument shops out, but it’s still a glimpse into the West End’s rich musical past.