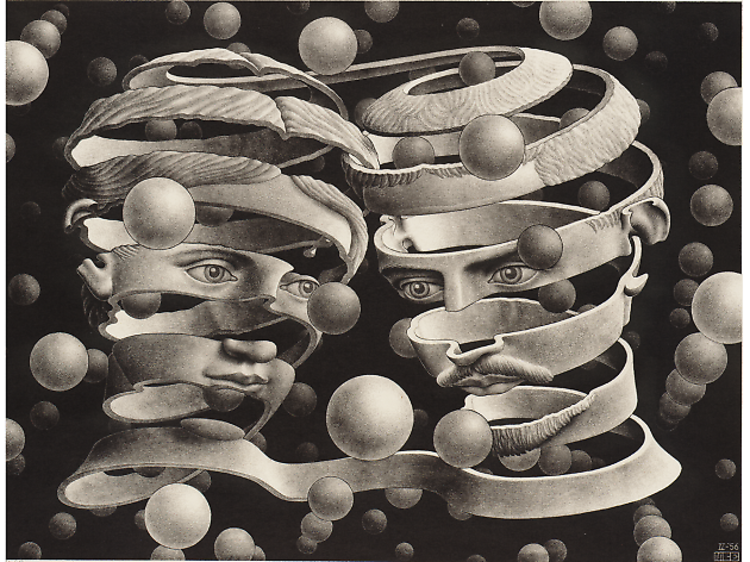

In a body of work full of paradoxes and apparent impossibilities, perhaps the greatest conundrum about Dutch artist MC Escher is that everyone knows his art, and no one knows anything about him. There’s no shortage of biographical information, it’s just that nobody seems particularly interested in him as a personality. But I think that’s very interesting. It’s like Maurits Cornelis Escher (1898-1972) is simply not seen as the creator of his work. It’s as though it had always existed, and he simply discovered it, like a scientist: ‘It’s very Escher-like’; ‘It’s clearly derived from Escher’ etc.

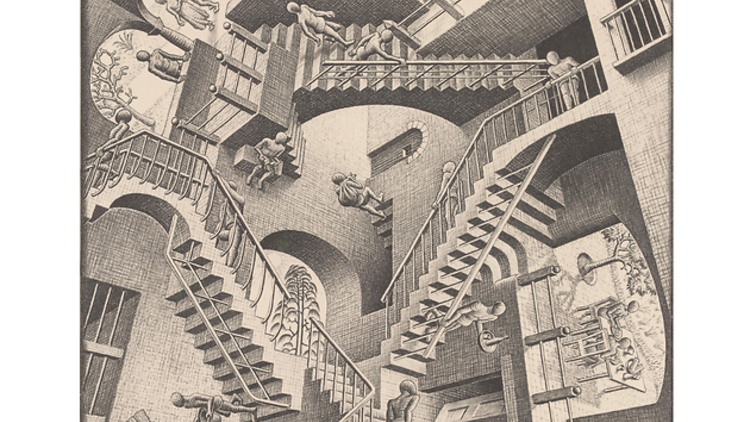

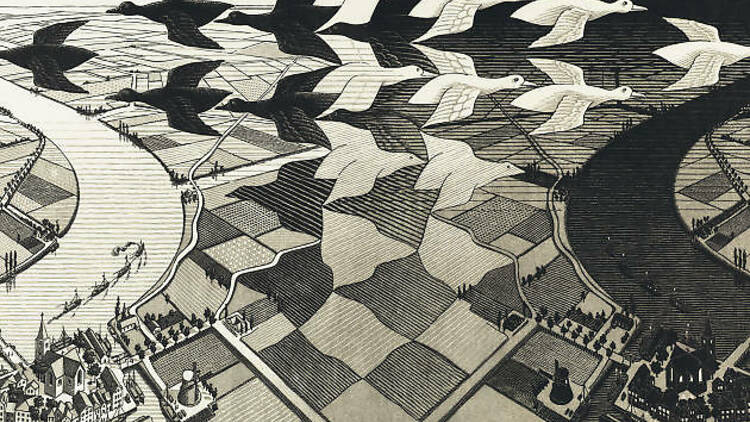

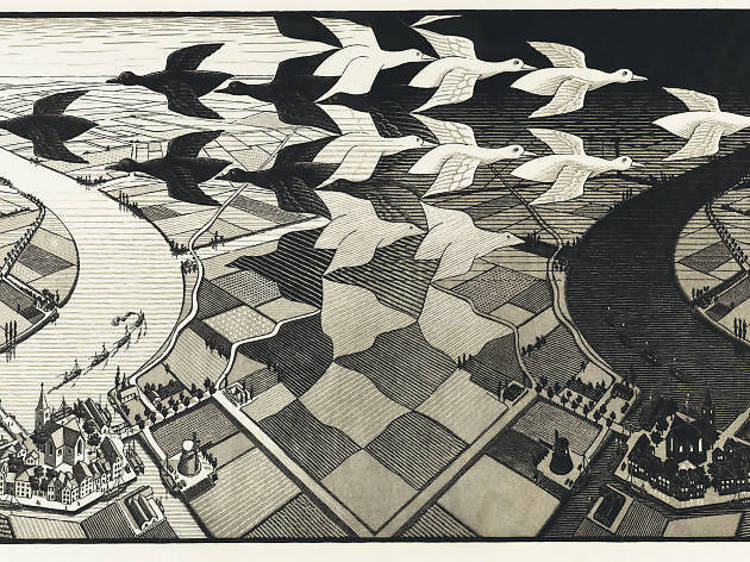

A new show at Dulwich Picture Gallery – incredibly, Escher’s first ever UK retrospective – attempts to flesh out these strange, obsessive, troubling works. Though maybe ‘flesh’ is the wrong word. Judging by his self-portraits, Escher was as ascetic and bloodless as his microscopically controlled art suggests. In his later years, he resembled Private Fraser from ‘Dad’s Army’, whose catchphrase ‘We’re doomed’ pretty much sums up the plight of the figures in Escher’s lithographs and engravings. Doomed to sit beside an endlessly self-replenishing waterfall for ever. Doomed to walk up a flight of stairs for ever. Doomed to be part of a tessellated pavement… for ever. Escher’s delineation of these spatial entrapments doesn’t suggest that they are romantic metaphors: he is a superb draughtsman and a forensic printmaker. Apparently he was annoyed by his growing fame in the 1950s and ’60s, since demand meant that he had produce so many copies of his prints, and he did them all by hand himself.

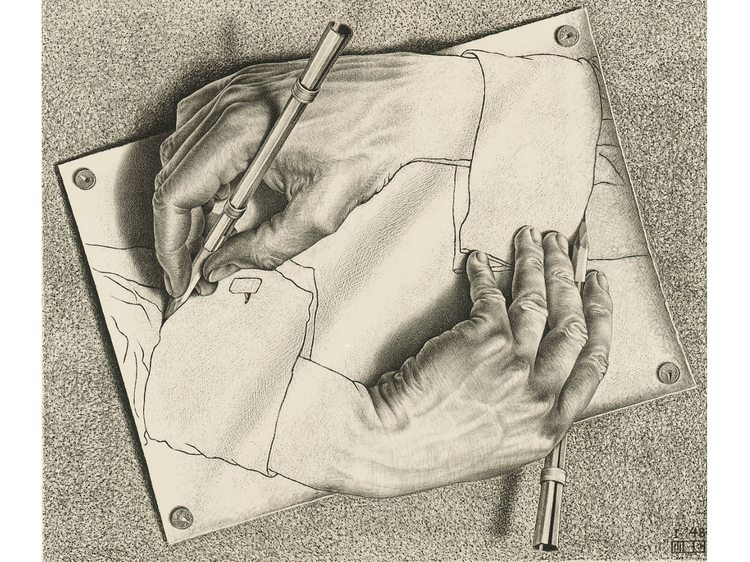

This show is a chance to look beyond the pothead pin-ups of Escher’s greatest hits and reappraise him as a person: a contemporary of the surrealists; a man who lived through two world wars; an artist whom the Rolling Stones asked to design them an album cover. And who refused. Ultimately, the artist remains unfathomable, but Sir John Soane’s eccentrically beautiful Dulwich PIcture Gallery is the perfect place to explore, in Escher’s words, the idea that, ‘in our three-dimensional world, the two-dimensional is every bit as fictitious as the four-dimensional’