Walter Sickert is disintegrating. He’s melting into nothing, disappearing right in front of you in a staggeringly good, muddy, sombre early self-portrait from 1896. This neatly encapsulates what makes the English painter (1860-1942) so interesting: it’s not his handling of paint or how he captures light or anything, it’s the bubbling undercurrent of darkness that courses through his work.

Because where the impressionists and their successors exalted in the effects of natural light, found ecstasy in the beauty of nature (easy enough when you live in the South of France instead of north London), Sickert’s work is caked in the filth and thick smog of the city, the grime and decay of Camden.

This show of art from across his long career takes in portraiture, landscapes, urban scenes, nudes and a whole bunch of murder. His early work owes hefty debts to his mentors James Whistler and Edgar Degas. He took the muted tones of the former, and the fascination with everyday life from the latter.

It’s deliberately provocative and disconcertingly morbid

Sickert, a former actor, repeatedly paints the stages and music halls he loved. There are actors frozen in searingly bright spotlights, draped in luminescent red and white dresses, trapeze artists caught mid-flight, singers caught mid-song. So far, so Degas, but the real gold is in the crowds. Sickert’s masses of rapt bodies are trapped in the gloom, shadowy observers that smudge into one another, becoming big anonymous, amorphous globs of fascination, the embodiment of the lecherous, threatening male gaze.

One stunning image shows the backs of a crowd at an early film screening, the movie barely visible beyond the countless gawping men. The screen is one of Sickert’s devices for twisting the way we look – as are mirrors, light sources, reflections and photographs. This comes across best in his portraiture. In one painting, a woman reaches up to fix her hair, craning to see herself in a mirror above a too-high mantelpiece; in another, an actress is shown with her face grotesquely mutated and disfigured by flickering lights below her chin. Later self-portraits are based on photographs from unflattering angles. He constantly uses the ideas of mediated vision – looking through mirrors, cameras etc – to mess with representation. Even his oddly dark landscapes are full of silhouettes and looming dark shadows.

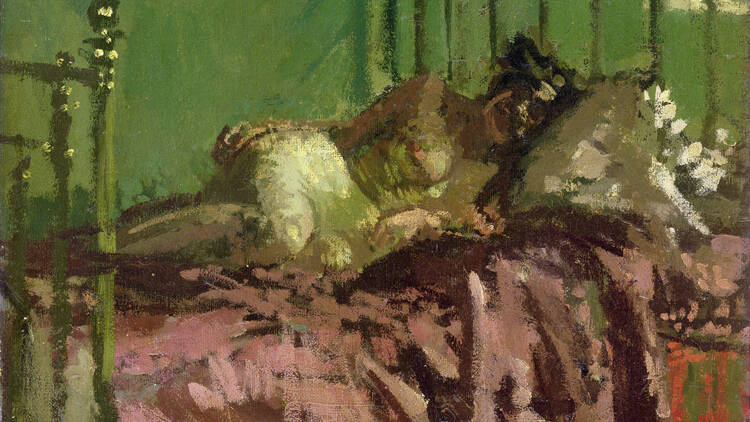

But the real darkness comes in the nudes. What starts out in the earlier works as an homage to the bare eroticism and vulnerability of Pierre Bonnard and Degas eventually morphs into something deliberately provocative and disconcertingly morbid. The bodies don’t seem posed but abandoned, their limbs slack and displaced, draped across filthy beds in nasty rooms. It’s tense, uncomfortable, gross. And then there are the ‘Camden Town Murders’ paintings, all filled with shameful, fully dressed men and apparently lifeless naked women. They’re intentionally controversial, publicity-hungry images (there are daft claims that Sickert could have been Jack the Ripper), but that doesn’t make them any less visceral or intense. They’re sinister, horrifying and totally captivating.

The biggest surprise of all here is how brilliant Sickert’s later works are. He loved working off photographs and press clippings, exploring the flatness and contrast the camera provided. His images of George V, based on newspaper photos, are wonky and oddly framed, his can-can dancers are stark and ghostly, and his jawdropping image of Sir Thomas Beecham conducting is the most bizarrely dramatic, blood-drenched portrait imaginable. In all the later works’ mechanised strangeness, manipulation of visual narrative and use of popular culture, you can see the birth of countless modern painters: Marlene Dumas, Gerhard Richter, Peter Doig. It’s amazing.

There’s a lot of derivative work here, and some very naff painting, but Sickert was a truly unique, very strange and unbelievably modern painter. And he probably wasn’t Jack the Ripper, so it’s all good.