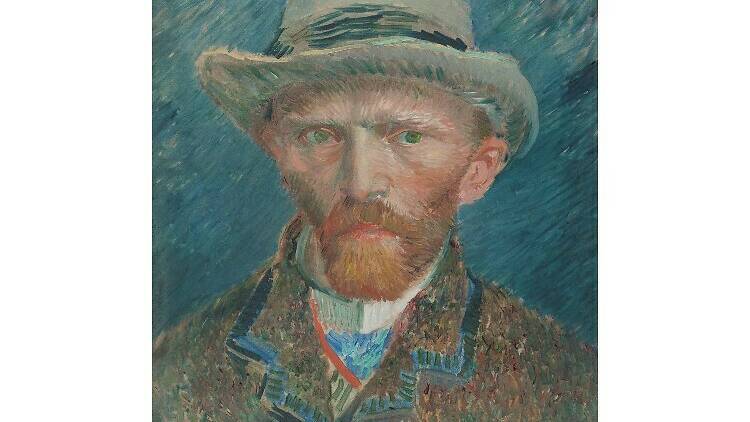

It’s hard to look him in the eyes, Vincent Van Gogh. His gaze is deep, over-intense, rigid, unending. You’d definitely avoid eye contact with him in a bar. But in self-portrait after self-portrait in this show, he stares right out at you, his eyes drilling straight into you.

He painted 35 known self-portraits, and a good chunk of them are on display in this neat little exhibition; some of them are masterpieces, some of them are total duds. It starts with his first works in Paris in late 1886. The earliest painting here is dark and brooding and filled with slabs of solid ochre and black, like a very moody goth Cézanne. It’s not the Vincent Van Gogh we all know.

But, influenced by the Parisian avant garde of the time, by early 1887 the colours are lighter and the brushstrokes have started splodging about in their millions. It’s recognisably and obviously Van Gogh. He’s not an assured painter yet though, lots of these earlier pieces are tentative, unsure, questioning – some aren’t even any good. But one spring 1887 piece, made of countless orange and green marks, is the real beginning of something. Vince looks like a creature made out of nature itself, like all the colours of the trees and flowers have coalesced into a man.

Eventually, he moves to the south of France, and it all comes to life. These are wild, personal, experimental works. In one he’s sickly and pallid in a world of bodily, crappy browns, in another he’s all swirling blues and dizzying, spiraling greens. It’s hectic, overbearing.

These are images of a man in various states of decay.

The Courtauld wants to tell you that Vinny used self-portraits to try out new ideas quickly, easily, cheaply. They’re insisting that this is about technique over feeling.

But that can, frankly, piss off. Because the great paintings here are great because of the emotion. All that swirling paint and spinning composition; these are images of a man in various states of decay, a man in the process of exploding into emotional static, constantly on the verge effervescing into nothingness. When he’s at this sickest – in an unbearably tormented August 1889 work – his gaunt, haunted face looks like it’s collapsing in on itself, while his edges are fraying and shimmering.

Just a week later and he’s become solid again, he’s just patches of orange and yellow in solid blue. This is a guy going through some shit, and working it all out in paint.

That’s what makes Van Gogh so special to so many. Yeah yeah, the sunflowers and stars are nice, but in his brutal, extreme, intense honesty, he becomes a container for our’s. We find beauty in the ups and downs of his emotional life because we’re desperate to find understanding through art.

What the impressionists did for light – exposed it, exalted it, wallowed in it – Van Gogh did for his own emotions. His story is tragic, but we’re lucky he told it, and told it so beautifully.