How much light can you pack into a painting? How much love, despair, hope, anxiety? In the case of Vincent Van Gogh, the answer is: infinite.

This mesmerising show of kaleidoscopic, emotional art brings together work from the last two years of his life, years spent in Provence turning painting inside out and mentally falling apart in the process.

It’s a show full of themes: poets, lovers, gardens, peasants. He paints the wild, rocky, parched landscapes of southern France, the psychedelic, jagged gardens of the asylum he placed himself in, the calm, domestic peace of his yellow house. There are figures here – walking down avenues, sitting for portraits – and there are things – sunflowers, teapots – but they all serve a purpose greater than their own representation: Van Gogh was trying to paint meaning.

In 1888, Vincent was living in a yellow house in Arles. Here, he painted figures as poets and lovers, couples wandering in the wilds, he painted fields unfurling full of allegorical intentions. He dreamed up ways to show his art to hipster cognoscenti up in Paris, he created groupings of works that would complement each other and unspool narratives.

Vincent was thinking about an art of the future, he was thinking about his legacy, his place in the history of art. That brings with it a sense of frustration. Van Gogh wanted a life of literature and poetry, of mythology and love, success and praise, adulation and camaraderie; these gardens and poets are hopes, dreams, ambitions that wouldn’t come to pass. And in late 1888, he’d suffer his first breakdown.

A bunch of swirling, seasick vortices of colour

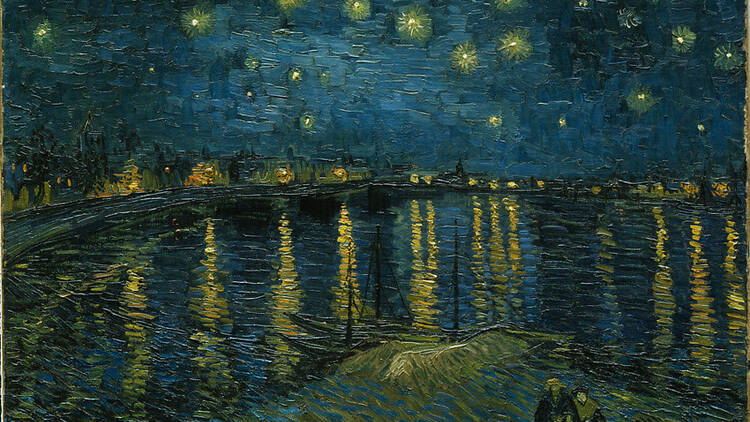

There are incredible moments in the 1888 paintings: ‘Starry Night’, the shimmering colours of his bedroom, the ghostly, solitary misery of the Trinquetaille bridge, the bulbous, surreal dominance of the plane trees. There are some awful paintings too, like the splodged mess of the green vineyard.

There’s also a sense of restraint. But in 1889, after the breakdown, he let loose. Now the landscapes of Provence morph and throb and spin. The world becomes a bunch of swirling, seasick vortices of colour. The olive trees spin, the sky spins, fields of wheat spin, blackened mountains spin. Peasants try desperately to hold on to a world that won’t stand still, try to work and live in a land that makes no sense. Amazing, wild, weird, tumultuous, unique, experimental painting.

In all honesty, Van Gogh leaves me a bit cold. But it’s hard not to read the work through the prism of his life and hardships, to see the undergrowth spreading like illness, the trees darkening with depression. There are boring art historians out there who want you to divorce Van Gogh’s work from his life, to take it at face value and for your reading to start and stop with the painting itself.

But that’s bullshit. This is art as a reflection of life, as an expression of love, fear, hope, despair, pain. He says it himself. He wants to ‘express the love of two lovers through a marriage of complementary colours’ in ‘Starry Night’, he wants to ‘give rise a little to the feeling of anxiety’ with the ochres, blacks and ‘green saddened with grey’ in ‘The Park of the Hospital at Saint-Remy’.

This isn’t the painting of light like the impressionists, or of reality, this isn’t literal representation, it’s the painting of emotion, and that’s why it’s good: because it means something.