London’s museums and galleries are enjoying a nostalgic love affair with the subcultures of 1980s Britain this year.

On right now are Tate Britain’s The 80s: Photographing Britain documenting the huge social upheaval of the era, and the Fashion and Textile Museum’s Outlaws delving into the fashions of the New Romantics. Next up is Tate Modern’s Leigh Bowery exhibition, highlighting one of the decade’s most significant cultural figures, followed by the Design Museum’s autumn exhibition on the era’s countercultural headquarters, the Blitz Club. And then there’s the National Portrait Gallery’s offering, The Face Magazine: Culture Shift.

Is five overlapping shows about Thatcher’s Britain too many? Not judging by the number of people that my dad would refer to as ‘older funsters’ poring over magazine spreads on the exhibition’s opening day. For Brits of a certain age, The Face was the pop culture bible of their youth. Its pages were a chaotic, colourful blend of music, fashion, nightlife, and subcultural anthropology, combining the grit, tone, and subject matter of the era’s music publications with the creative flair, quality, and splashy colour photography of the big fashion magazines.

All of this is expounded in effusive hyperboles on the wall text at the beginning of the exhibition, a co-curation between the Portrait Gallery and former employees of the magazine. Setting the scene at the entrance is a pleasingly nostalgic video montage of scenes from 80s Britain. Thatcher gives a speech, protesters carry placards declaring ‘Victory to the Miners’, ravers dance, mohawked punks snog and Blitz Kids pout with faces of white makeup, soundtracked by ‘Buffalo Stance’, the hit single by frequent The Face model Neneh Cherry.

[it makes] this internet-pilled journalist yearn for glossy spreads that smell of fresh ink

The next room does a great job of concisely explaining the context within which the magazine launched in May 1980, detailing founder Nick Logan’s previous successes with NME and Smash Hits, and describing the creative freedom afforded to the enthusiastic young staff by the magazine’s egalitarian, anything-goes attitude via quotes from former photographers, writers and subjects.

Sitting alongside photographs of John Lydon, Adam Ant, Grace Jones and David Bowie are glass cases display some of the more zeitgeisty features from the magazine’s first decade. A (pre-cancellation) Julie Burchill piece on Thatcher and an essay on the AIDS crisis feel like invaluable historical documents, while a report on the nascent Blitz club scene and a double-page illustration of ‘The Chronology of Nightclubbing’ make this internet-pilled journalist yearn for a return to the days of glossy spreads that smell of fresh ink. Instagram reels just aren’t this beautiful.

The next couple of rooms explore some of The Face’s innovations over its first decade. There’s a room dedicated to the magazine’s association with the Buffalo movement, irreverent approach to menswear styling and pioneering use of Black models, and one looking at its photographers’ early experiments with post-production and digital manipulation, some of which look charmingly amateurish today. Some of these themes are more curatorially sound than others; a room devoted to the magazine’s coverage of clubbing and nightlife repeats some of what’s come before, but it doesn’t really matter when the real aim is to bombard you with as much of the magazine’s brilliant photography as possible.

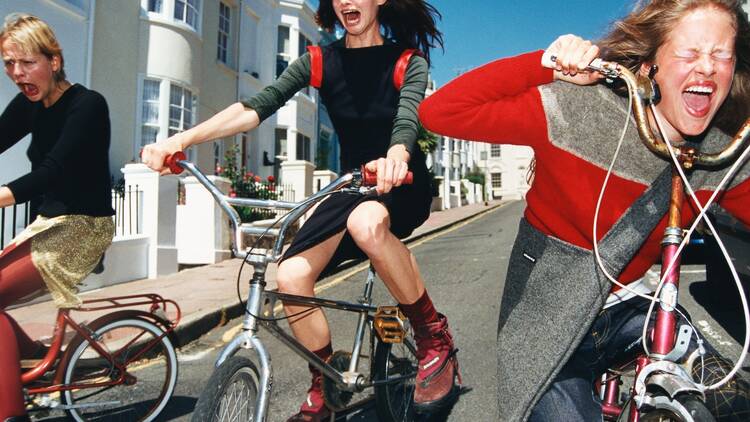

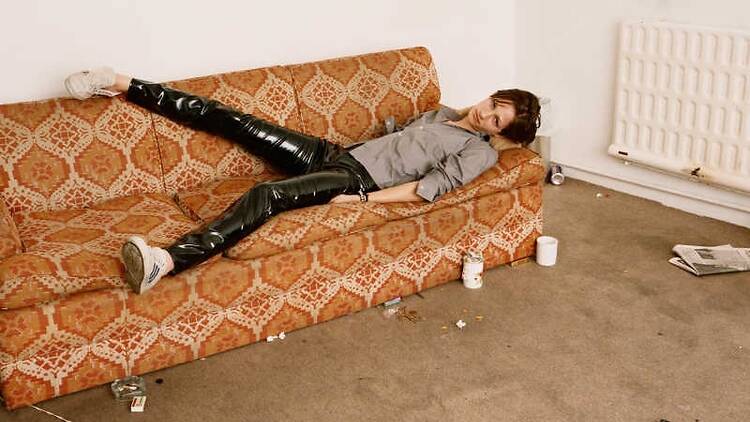

There’s a black-and-white headshot of a scowling young Liam Gallagher; a fresh-faced 19-year-old Kate Moss on her first cover; the newly-formed Spice Girls larking about in front of a chainmail fence Shoreditch Park; Blur, dressed in business attire, pretending to hail taxis on Westminster Bridge; a sallow, red-eyed Alexander McQueen looking like some sort of Celtic vampire; mohawk-era David Beckham glistening with sweat, coffee dribbled down his toned abs to look like blood; a liberally fake-tanned Girls Aloud sitting in an Italian cafe in trackies. Just about every UK pop culture icon of the last 40 years is present, among plenty of eye-popping and properly creative fashion shoots, and a bunch of youthful, hedonistic, wonderfully British street photography.

There are some minor grumbles. Maybe it’s not my place to say so, but the cultural impact of rival magazines (iD, Dazed, this very publication) feels noticeably absent from the exhibition’s narrative. And the closing chapter documenting the magazine’s relaunch in 2019 is a couched in jarring buzzwords, boasting that the title remains as disruptive and boundary-pushing as ever while ‘successfully navigating’ today's challenging media landscape.

But who really cares what the wall text has to say when you’re surrounded by photography this vibrant, energetic and cool? Take it from this writer; it’s all about the pictures in the end.