Cows were fine. Saints were fine. Even Christ on the cross was fine – as long as it was painted by a classically inspired Italian with an unthreatening sense of decorum and a buttery touch. Someone like Raphael, whose demure 'Saint Catherine of Alexandria' (1507) greets you as you enter the National Gallery's 'Strange Beauty' exhibition.

What absolutely wasn't fine in the 1820s and '30s – when the National Gallery lurched into life, first in a Pall Mall townhouse then in the purpose-built Trafalgar Square home it occupies today – was the kind of in-your-face, highly expressionistic sixteenth-century paintings hanging in subsequent rooms of this scintillating show. Lucas Cranach's 'Cupid Complaining to Venus' (1526), for example, with its bony nakedness explicitly on display. 'Too nude,' says Susan Foister, deputy director of the National Gallery and co-curator of the exhibition. Or Albrecht Altdorfer's anguished portrayal of 'Christ Taking Leave of his Mother' (1520). 'They were quite worrying,' explains Foister. 'I think people found them indecorous, something that was so stark that it couldn't really be consumed in polite society.'

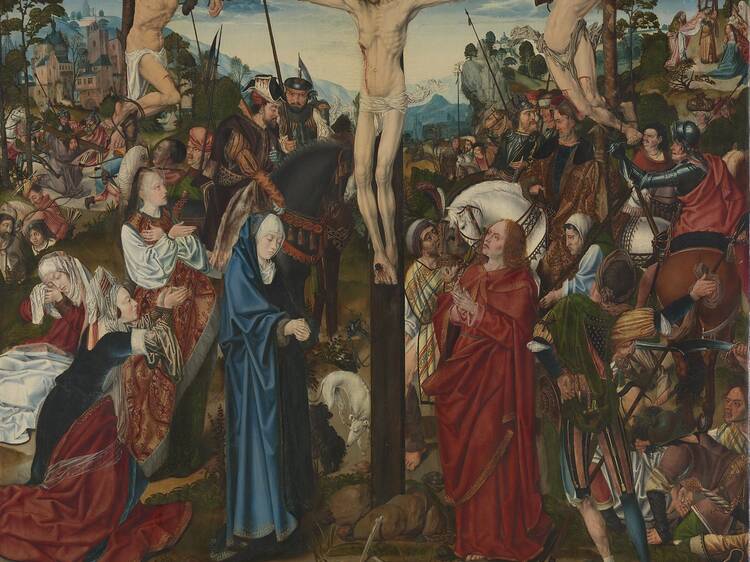

Despite Queen Victoria getting hitched to Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, this sentiment prevailed throughout the nineteenth century, with the more lurid imaginings of Catholic Germany ruffling the crinolines of stuffy, Protestant Victorian London. It created a climate in which one of the most unusual episodes in the National Gallery's history took place. In 1856, an act of parliament was passed so that the gallery could sell off part of the Kruger Collection of early German art, which had been purchased just two years earlier by William Gladstone. It led to the now inconceivable breaking up and scattering across the globe of the Liesborn altarpiece.

While attitudes did soften towards the end of the 1900s, two world wars ensured German art was off-limits during the first half of the twentieth century (Cranach's Cupid, for example, wasn't purchased until 1963). 'Strange Beauty', then, is a story not just of changing attitudes towards the body in art but of how a significant portion of the National Gallery's collection was amassed. 'It's a story we can't normally tell in the galleries,' says Foister. 'I think it will be quite a revelation to most people.'