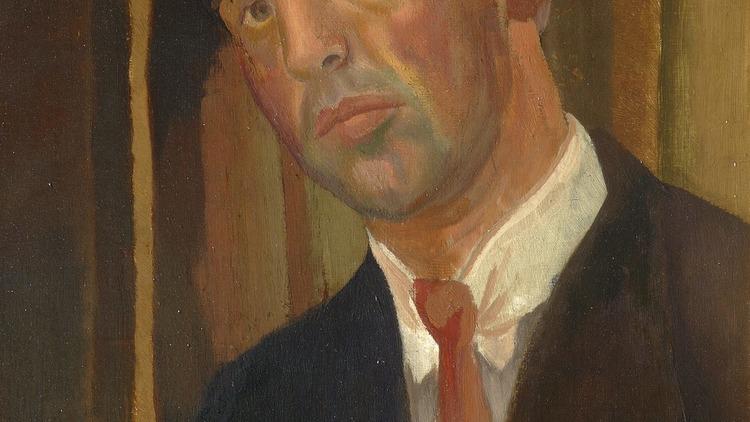

Stanley Spencer’s epic paintings for the Sandham Memorial Chapel, near Newbury in Hampshire, are among the greatest war memorials of all time. Looking at the 16 huge works, temporarily relocated to Somerset House as part of the run-up to next year’s WWI centenary, it isn’t hard to see what made them so groundbreaking when they were created between 1927 and 1932, and continues to make them so absorbing today.

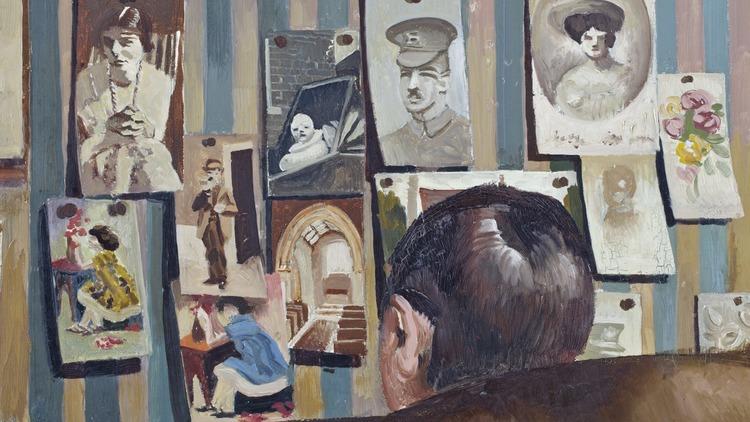

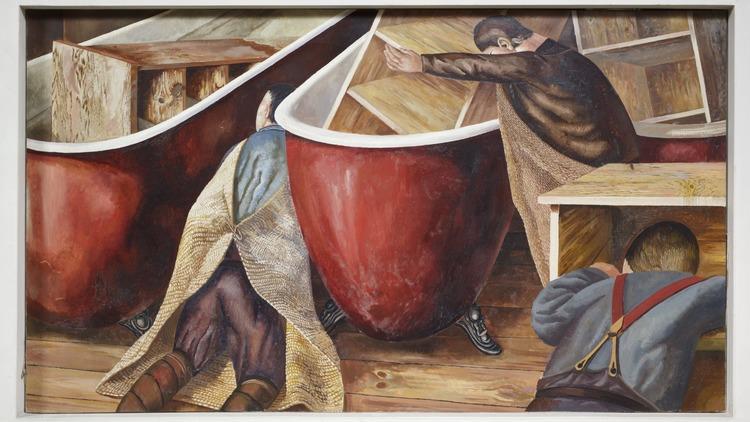

Instead of depicting combat or acts of military heroism, Spencer portrayed soldiers’ everyday lives. Scenes, teeming with activity, see men sorting out kit at a training camp, or pottering about in the trenches. But the main focus is a military hospital in Bristol, where Spencer worked as a wartime orderly, and whose enormous gates swinging majestically, almost divinely, open to receive truckloads of the wounded form the first image that greets you in the exhibition.

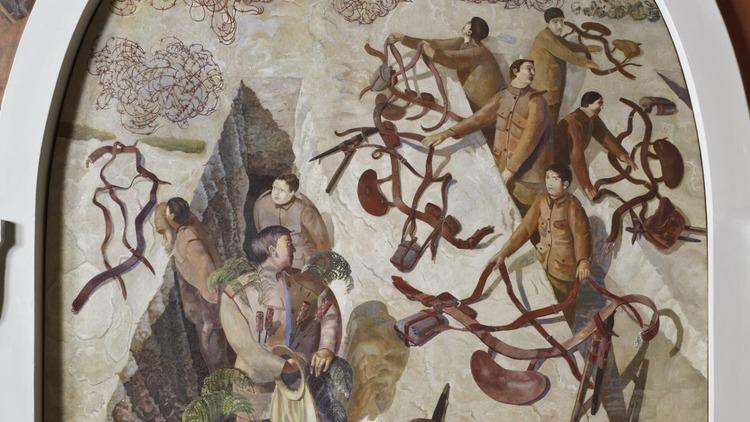

There’s a strong strand of religious allegory running through the works – from an orderly’s outstretched, cross-like arms as he makes a bed, to the soldiers’ capes that hang from their shoulders like angelic wings. This devotional tone is to be expected from Spencer, a devout Christian who believed the miraculous could be found in the mundane, especially in pieces that are normally shown in a chapel. Yet it also points to the fact that this London exhibition feels strangely decontextualised. Specifically, of course, what it’s lacking are those parts of the chapel which are immovable: Spencer’s murals, in particular his famous altarpiece depicting resurrected soldiers, which at least is represented here as a lifesize photographic projection.

More generally, though, the show is missing that absolutely crucial sense of being surrounded and immersed, of being literally within a single work of art. Undoubtedly, more people will view these individual paintings than will ever make the pilgrimage to the chapel – but maybe that pilgrimage is part of the work.

Gabriel Coxhead