My political leanings were very much to the left, unlike a lot of my friends in the Independent Group who thought it was fashionable to be apolitical, so I made a decision to do a painting that was excited by the situation of wars or what made me angry.

I'm 88 years old, so I lived through WWII when atomic bombs wiped out Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In the early '60s, the Labour party more-or-less decided to abandon all nuclear weapons until its leader, Hugh Gaitskell, convinced his deputy to make a powerful speech saying that England shouldn't go 'naked into the conference chambers of the world' - by which he meant without a nuclear bomb. To match this unpleasant and inhuman point of view I made a savage and expressionistic portrait, "Hugh Gaitskell as a Famous Monster of Filmland" (1964), which was the beginning of my interest in the possibility of political painting.

It seemed successful in so far as it was the first time that one of my pictures ended up on the front page of a newspaper. None of the other work I'd done before seemed to have had an effect on anybody; it was regarded as rather obscure and meaningless. My cool cloak was momentarily cast off.

It was very often newspapers or the television that introduced me to an image, so I decided to sit in front of the TV for a week with my camera. On the Wednesday news there was a perfectly reasonable student demonstration about the Vietnam War in an American university, but the authorities brought in the Civil Guard. To my astonishment, somebody started shooting and several students died. I was shocked and didn't want to exploit this horrific event, but on the other hand, there was a reason to continue making my prints of "Kent State" (1970) because it would keep the event in the minds of people for a long time, if what I did was meaningful.

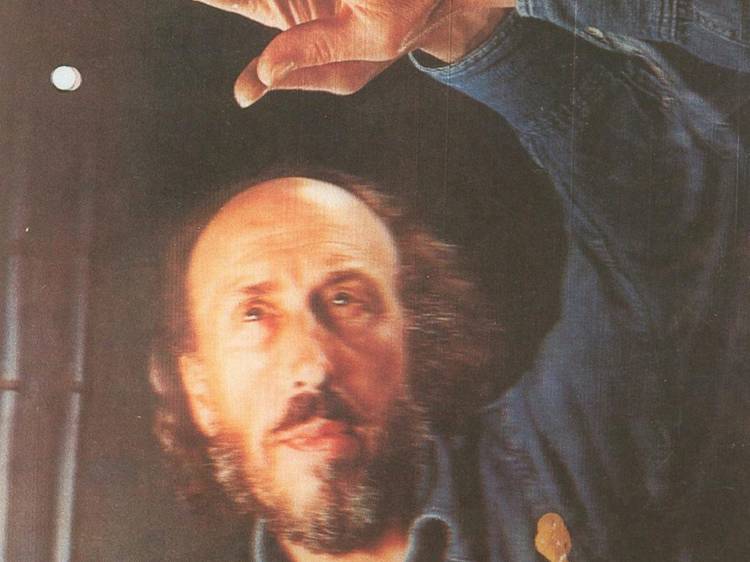

The next big moment of my political life was the sight of people in the Maze prison putting their excrement on the walls in the so-called "dirty protest". It had been going on for three years before the authorities allowed a camera in, but the cells were so small that you never saw anything but details. I wanted a full, monumental figure so I began to collage photographs together and the result was my picture of hunger-striking IRA member Hugh Rooney, called "The Citizen" (1982-83).

Several years later, the next piece in the sequence, called "The Subject" (1988-90), showed the other side of the coin and depicted one of the Orangemen marching through the streets of Belfast, in his strange Masonic uniform. In the top corner, there's an echo of the same window from the previous picture, only he's on the outside of the prison, while "The Citizen" remains on the inside. The next painting, "The State" (1993), completed the triptych and showed one of the patrolling British soldiers who had gone to Northern Ireland, at first, to try to help. But, as with every battle - whether it's in Afghanistan, Iraq or Palestine - these problems occur when civil liberties are deprived.

"War Games" (1991) was again the result of watching TV, when John Snow delivered his report on activities in Iraq with a big sandpit and these models of tanks and troops coming from America or Britain. Pushing these bits of balsa wood about seemed like a game and yet it was also very sinister.

Political pictures have different effects - whether moving effects of a depressing kind or effects that can linger for a long time. Some critics have said that subjects such as nuclear disarmament have lost their interest, but my inclination is that they've become more powerful as time goes by, rather than less. For example, after I saw an image of Tony Blair looking smug after a conference with George Bush I got my assistant to stand in as Blair and put on a cowboy shirt, guns and holsters. The result, "Shock and Awe" (2007-10) was a representation of my feelings about Blair but I've had a lot of criticism for this work. It's a question of timing. I'm sure that it will find its power as time goes by and becomes history. It seems necessary that an artist's attention should be directed at these problems, so I'm not going to give up.'

Read more

Top art features

Discover Time Out original video