Paul Klee is forever associated with his famously quirky description of drawing as ‘taking a line for a walk’. The stories about the Swiss-German artist that have stuck since his death in 1940 are similar eccentric. There’s the tale of his first day of teaching at the Bauhaus in 1921, when Klee, then aged 41 and already well-known in Europe, is said to have backed through the door of the classroom, avoiding eye contact with his students, drawn two arcs on the blackboard and declared: ‘This is the fish of Columbus!'

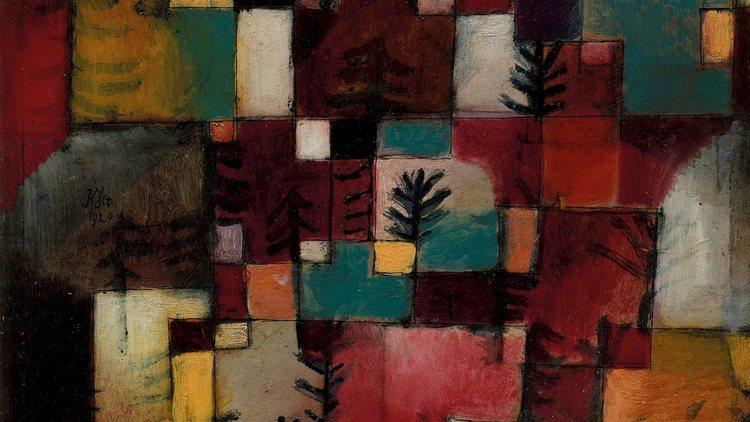

Another anecdote from around 1930 – by the American art collector Edward MM Warburg – places Klee in his Dessau studio. When the artist’s beloved cat Bimbo ambles across the still-wet watercolours they are admiring, Warburg tries to shoo it away. Klee, however, just laughs and says: ‘Many years from now, one of your art connoisseurs will wonder how in the world I ever got that effect.’ These accounts are of a piece with Klee’s endlessly innovative and apparently effortless paintings and works on paper, with their flowing lines, glowing patchworks of colour and whimsical depictions of animal, plant and sealife.

‘Klee’s work is always about what it means to be in the world, how to process it,’ says Matthew Gale, curator of the first Klee exhibition in London for more than a decade. Yet, behind the freewheeling genius there was another, altogether more obsessive side to this modern master. Throughout his career, Klee used a variety of numbering systems – made up of the year, month and day – as a way of documenting his prodigious output. His apparently spontaneous creativity, which led to a total of 9,000 works being produced during his lifetime, was always held in check by this analytical approach to numbering his work. It was his way of revisiting what he had made, making sense of quickfire artistic impulse. Featuring around 200 paintings, Tate Modern’s new show foregrounds this characteristic, using it to delve deep into Klee’s creative processes. ‘The way in which the exhibition is structured derives from Klee’s own numbering system, which he started in 1911,’ explains Gale. ‘The purpose is to show the incredible diversity of his production.’

Museum exhibitions are great at presenting us with end results – those polished, cherished icons of art history. They’re often less adept at revealing how those results came into being. We can’t time-travel to enter Klee’s studio and see how his works progressed but – in offering up paintings made in sequence – Tate Modern’s show gives us the next best thing. Moving through the exhibition is like seeing a series of snapshots of Klee’s working life. You’ll discover how paintings developed in tandem or relay, like the Tate’s famous watercolour ‘They’re Biting’ (1920), which is flanked by works that precede and follow it. Tate’s reappraisal sheds light on dualities in Klee’s character. He was a talented musician (he played the violin, often to make ends meet) as well as an artist. He was ambidextrous, painting and drawing with his left hand while writing (and signing the work) with his right. ‘I think cataloguing the work allows him to have a structure,’ explains Gale. ‘This clear, orderly side to him means he can open the door of his studio and range freely as his imagination allows him.’

If Klee is underappreciated in Britain, Gale puts it in part down to fashion: ‘We’ve passed through a sort of dip in his reputation and I hope that we’re going to inspire a new generation to look at Klee in a different way.’ It may also be due to the juggernaut of art history. While Picasso will forever be linked with cubism, Matisse fauvism and Seurat pointillism, Klee’s fame may have suffered from a lack of ties to any particular art movement. ‘“Isms” aren’t everything,’ says Gale. ‘I think the fact that Klee isn’t associated with an “ism” can make him difficult to categorise, but I think that is probably also the strong point in his legacy – that he provides an example of an incredibly rich creativity that’s not pigeonholed.’ Klee was certainly celebrated in his lifetime, with a solo exhibition at the Nationalgalerie in Berlin in 1921 and a retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1930. During the final decade of his life, Picasso and Wassily Kandinsky came to pay tribute to the master in Bern, Switzerland, where Klee took refuge after his work was deemed ‘degenerate’ by the Nazis and he was dismissed from his teaching position in Düsseldorf.

By this time he had been diagnosed with scleroderma, a debilitating hardening of the skin. Klee’s numbering of his work didn’t stop but his production became erratic. In 1936, he produced just 25 works, while in 1939 he made more than 1,000 paintings and drawings that ‘fell like leaves’ around him. The last work he numbered in 1940, a leap year, is 366. ‘There seems something very symbolic about stopping with that number as if he feels he’s completed that year’s work,’ says Gale. ‘He clearly knew he was dying.’

While this casts a shadow over Klee’s later works, many of his final paintings are defiantly upbeat, like the joyously rhythmic ‘Twilight Flowers’ (1940). It’s this sense of playful enquiry about the world which Gale hopes visitors will take away with them. ‘I think you’ll get a sense of the amazingly productive journey he goes on, and go away inspired to make work yourself, in whatever realm. Klee wrote, as well as playing the violin and painting, making his own brushes and puppets for his son. His is not an exclusive sort of creativity but one that encourages you to explore that creative part of your life.’ Who knows, maybe you’ll even get the cat to take a line for a walk too.

Paul Klee at Tate Modern: curator interview

They called him the 'Bauhaus Buddha', but painter Paul Klee was both mystical and highly methodical. Ahead of a major Tate Modern show, curator Matthew Gale talks about the two sides of this legendary modern artist

Discover Time Out original video