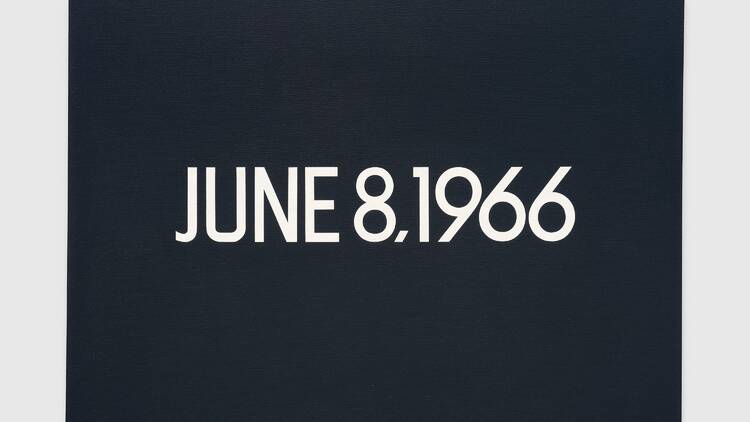

On Kawara did one thing, every single day, for most of his life. Over and over again, he painted that day’s date, always in white, usually on black, sometimes on other colours, but with no other variation.

Why did he do this? I don’t know. Something to do, I guess. Why brush your teeth, why go to work, why repeatedly update your fantasy football team throughout the week? Because what else are you going to do? That’s life.

It really is just dates, painted meticulously and precisely. But I find myself obsessing over the minute, pointless differences. Why does he sometimes do day/month/year, sometimes month/day/year, why is it ‘June’ and ‘July’ but only ‘Nov’, why is ‘Août’ written in French, why is one of them red, and a million more tiny differences. It’s a subeditor’s nightmare.

This is literally everything, the whole world is here!

But those tiny insignificant discrepancies are the tiny insignificant discrepancies of everyday life, they’re the new pair of boxers, the different route to work, the friend you haven’t seen for years, the thing that makes each day separate, and somehow remarkable.

It might feel like I’m reading a lot into some dates painted on black canvases, but that’s On Kawara’s point. These aren’t really paintings, they’re an idea, an idea he’s expressing through the act of painting. He’s marking the passage of time, the slow ebbing away of life, in the simplest way possible. When I was at the gallery an old lady asked the gallery assistant ‘is there anything else?’ Anything else?? This is literally everything, the whole world is here! In this basic, bare, minimal nothingness is all of life, there’s nothing else because this is everything.