You might think that the Science Museum is an odd place to go and see an exhibition of photographs about housing in Britain 45 years ago. You might also think that an exhibition about housing in Britain 45 years ago doesn't really sound much like 'art'.

Though he's not well known, Nick Hedges is a great photographer. And as for the venue, it's a tragically appropriate place to see a photograph of a family in this country living without water, heating, sanitation or natural light in the year man walked on the moon.

Between 1968 and 1972, Hedges was commissioned by the housing charity Shelter to document the appalling conditions in which hundreds of thousands of people were living. For four years he visited the most deprived areas of the country, including Glasgow, Bristol and the capital. He was in his early twenties, and had come to the project after Shelter co-founder Des Wilson saw his degree work about slum families in Birmingham. 'I was quite unassuming,' Hedges says. 'I didn't look like a photographer. They didn't immediately think: This is someone from outside.'

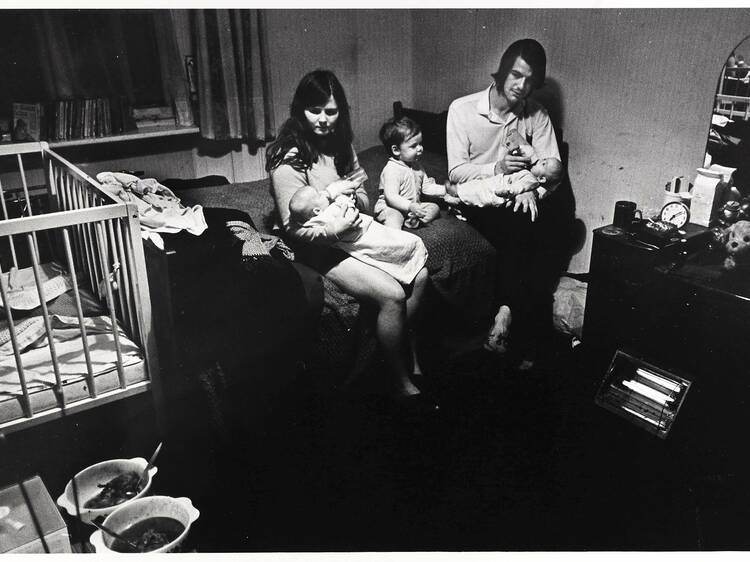

Being accepted by the communities and families he shot gives his photographs an incredible immediacy, framed by his own technical skill. Inevitably, given the circumstances under which they were taken, many of the images are brutally stark: gaunt figures huddled on beds, lit by bare bulbs or by grimy windows. Light is a commodity, they seem to say. Not everyone can be lit.

This was the Britain that no one wanted to see

This is not the groovy 1960s of films such as 'Blow-Up'. It looks more like the 1860s. David Bailey might have taken the odd jaunt back to the East End to give Sunday Times readers an edgy thrill, but this was the Britain that no one wanted to see, least of all photographers. 'There wasn't really an appetite for this work,' says the show's co-curator, Greg Hobson, who compares it to Walker Evans's documentation of the Great Depression in the States. 'On the one hand, there's this appetite for desperate situations overseas, but the minute that people have to address it on their doorstep, they don't want to look at it.'

In fact, Hedges has some of the war reporter's tenacity and tenderness. He cites Philip Jones Griffiths, who worked in Vietnam, as a photographer he admires, and he suffered his own homegrown version of combat fatigue: 'Two places stand out for me,' he says.

'One was the multi-let housing in Liverpool. It was horrifying: people living in cellars. I was very shocked by it. The other was Glasgow: just the amount of slum tenements in the Gorbals and Maryhill, they went on and on and on.'

London, meanwhile, revealed different problems. 'It was patchy,' Hedges says. 'In a street you'd get maybe one or two very bad houses, then three or four that were fine.' Children are the focus of many of the images. They're usually either in big huddles, showing how many people were crammed into one or two rooms, or quite alone: although grimly repetitive, this is an existence of extremes.

Many of the pictures haven't been exhibited before: Hedges embargoed their publication beyond Shelter's reports to preserve the privacy of his subjects. Those people's dignity and the sense of community in many of the photos owe as much to Hedges's empathy as a photographer as to his subjects' determination to carry on, but he's under no illusions that the issues he confronted with such sensitivity have disappeared.

'These are historical photographs,' he says. 'They're 40 years old. But while material circumstances have changed, the anxiety and tension and pressure that people feel is just the same now as it was then.'