Bankers at nightclubs aren’t Mark Neville’s usual territory. The artist is more likely to be found embedded in a former ship-building community like Port Glasgow, Scotland, or with the 16 Air Assault Brigade in Helmand Province, Afghanistan. Why? He wants to deepen art’s social usefulness by changing the way these communities are photographed or filmed, and it’s unclear why the revellers at London’s Boujis nightclub, famous for being Prince Harry’s favoured hangout, qualify as a troubled community – troubling, perhaps.

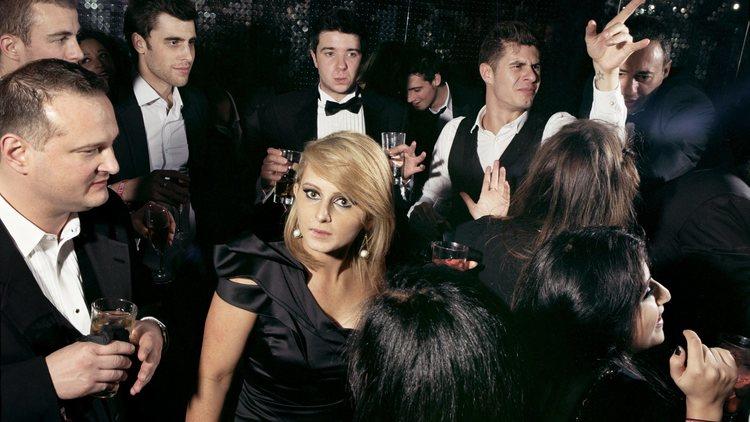

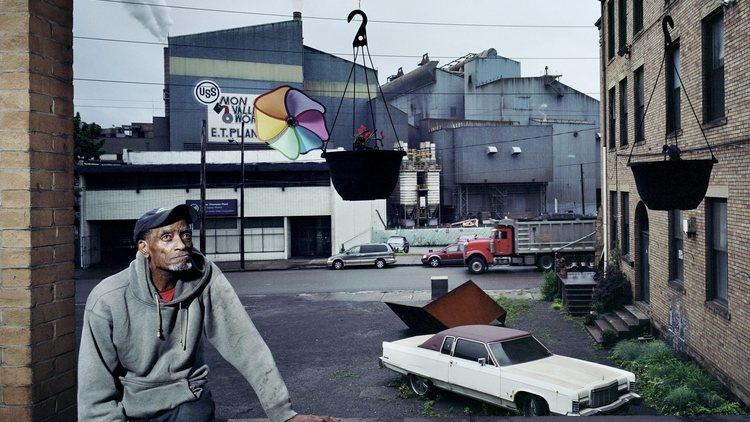

For this exhibition Neville presents 13 large-scale images from two projects first displayed in 2012. For ‘Here Is London’ Neville contrasts rich ravers in Kensington with poor residents in Tottenham. While ‘Braddock/Sewickley’, shot in the US’s former industrial heartland of Pittsburgh, reveals the deep and predictable colour and class divides that still abound. These disparities – rich and poor, white and black, UK and US – are oddly unsatisfying. On the dancefloor, a white, British babe in a scarlet dress cuddles herself in an ecstasy of narcissism, while equally coiffed banker boys stare down her low-cut dress. If, in another image, a black American woman, wary but unflustered at a very different party, wears an equally scarlet dress, cheaper, lower-cut and accessorised with tattoos, what conclusions should we draw?

These shiny, massive images, intricately structured and undeniably powerful, conform to our prejudices in a bothersome way. Black American kids in a deadbeat town fake their aggression and eat junk food. Tottenham mothers have tight jaws and disconcertingly resigned offspring. Parties in working-class Braddock seem almost to drip moisture, so cloistered and sweaty are they, in contrast to the pleasing light gloss of perspiration on the Boujis crowd. Surely these things are true: working-class mothers have little patience, violence looms over poor black kids, and wealth makes even sweat sweeter. But didn’t we already know all that?

Nina Caplan