It might seem like it sometimes, but European art didn’t evolve in a bubble. For centuries, millennia even, western art existed in dialogue with art from the east. In the same way that black pepper made its way over from India and set European palates on fire, so the colours, shapes and intricacies of the East lit a flame under European culture.

This small exhibition aims to show the Islamic influence on Western art, but that’s not really what it does. Instead, it shows you the beauty of Ottoman and Persian artefacts and drawings, and the fascination they held for western audiences; then, it takes you on a heady trip through Orientalist paintings, before dumping you in front of a handful of contemporary artworks. What it fails to do is draw any links between any of those things.

It begins darkly and hypnotisingly, with objects and works on paper from as early as the fourteenth century. There's a stunning Ottoman helmet seized in Vienna in 1683, fluidly decorated plates, prized silk purses. Gorgeous stuff. Then you find sixteenth century Flemish drawings of Ottoman women sitting back-to-back with Ottoman drawings of ludicrously dressed European men. This was a time when empires were ebbing and flowing, with Turks in Austria, Moors in Spain: a back and forth of power, ideas and aesthetics.

But by the nineteenth century, the West had cemented its dominance. The East had become the ‘other’, not ‘another’: they were the wild, unknowable savages of the Orient. And now the West had an appetite for their stories, for an insight into these hot, dusty, magical, faraway lands, and artists were happy to provide.

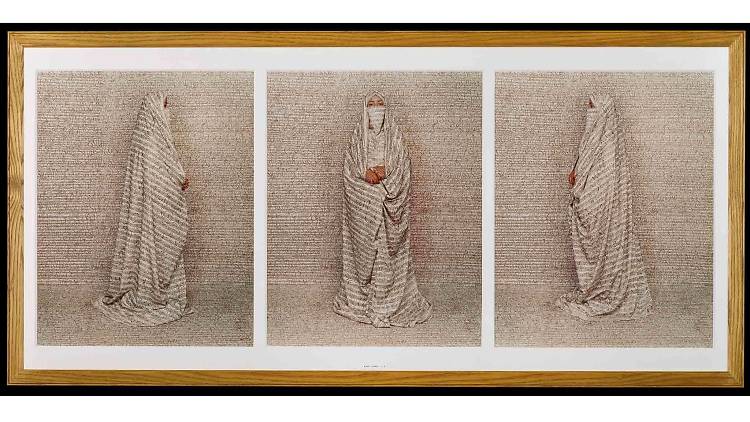

The Orientalist images here find European artists painting the Hajj, praying men, exotic architecture, Middle Eastern street scenes and a LOT of harems. The works are often beautiful, but they’re undoubtedly ‘othering’, just a chance for Europeans to gawp.

It’s also a shame – though understandable – that they’re missing some of the great works of Orientalism (Delacroix and Ingres, for example, though both are here in sketch form). More than anything, though, this doesn’t deal with the show’s premise. It goes from dialogue and influence to a singularly Western vision of the east. You want more about the influence and power of Islamic art, more about what it actually changed. And the final room of contemporary works is too small and slapdash to be anything more than an afterthought.

But where this show succeeds is in undermining a totally Western view of art. It shows you that Europe didn’t evolve in a bubble, that culture is an exchange, a conversation, and if take the Islamic world out of it, we’re just going to look like we’re talking to ourselves.