Graffiti has always been a dirty word for a dirty art form that blights our city’s walls and trains. Night after night, indecipherable tags and secret codes are scrawled on railway sidings and pedestrian bridges, while dripping silver spray paint smears every other high-street shopfront. Most passers-by are immune to its messages; others are confused or angered by the visual intrusion into their daily commute.

Yet, all of a sudden, the newspapers are full of stories – seemingly from a parallel universe – in which anger is vented at ignorant councils who whitewash over treasured illegal murals and masterpieces painted by hooded men under the cover of darkness. The media frenzy has, so far, centred on the graffiti world’s very own Scarlet Pimpernel – who may or may not once have been a bit pimply himself – the bearded Bristolian thirtysomething called Robert Banks, or just Banksy. He could also, like Spartacus, be tall/short, fat/skinny and black/Asian, depending on whom you believe.

Banksy’s signature stencils of kissing coppers, flower-chucking terrorists and mischievous rats found on doorways and side streets have become so sought-after that they are being chipped out of walls and sold for ludicrous sums, exactly mirroring the early ’80s phenomenon of Brooklyn-born graffiti kid SAMO (better known as troubled painter Jean-Michel Basquiat). Like New York in graffiti’s heyday, London is now embracing its disenfranchised plein air daubers, except that they are no longer derided as criminals or vandals but lauded as ‘street artists’.

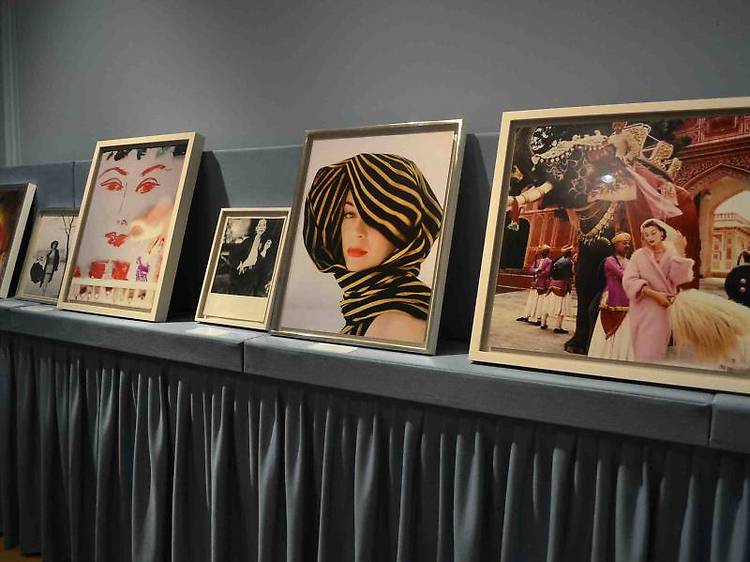

This newly acceptable form of graffiti is currently storming the traditional bastions of high culture. On Tuesday, venerable old Bonhams is holding the capital’s first dedicated auction of ‘urban art’ in Bond Street (not exactly its natural habitat), and Tate Modern will be dedicating a weekend to the arrival of the street art genre in May. With such establishment credentials come big money opportunities, but also huge contradictions. How can you call yourself a street artist when your work is hanging in a gallery or depicted in an auction catalogue or emblazoned on a promotional T-shirt? When ad agencies are employing graffiti artists to make their products look cool, doesn’t your raison d’être as an illegal, guerrilla artist implode?

Already, Banksy’s pseudo-anonymity has come to seem less of a necessity to avoid prosecution for his years of paint-inflicted property damage and more a ploy to maintain his aura as international man of mystery. It may also backfire on him, as fraudulent Bansky prints have been peddled on eBay and any number of unscrupulous art dealers continue to sell secondhand Banksies as though they’re his official agents, when in fact he has only one (gallery owner Steve Lazarides). In spite of the circling wannabes, a whole street art industry is forming around young galleries and artists selling prints and unique pieces. So, while the current boom may have begun with Banksy, his witty one-liners won’t be the last word in street art.

It all began in the mid-1980s as London’s hip hop scene – also imported from New York – began to grow, especially in inner-city areas such as Brixton and Westbourne Grove. Small brigades of writers began tagging their names all over town, with pseudonyms like Robbo and Drax (taken from James Bond’s enemy in ‘Moonraker’) seemingly ubiquitous on every tube line. The most famous was Mode 2, who set up the first renowned graffiti crew, the Chrome Angelz. Soon, designated graffiti ‘halls of fame’ sprang up in housing estates and train yards from Hammersmith to Neasden. By 1987 the British Transport Police (the dreaded BTP) had launched a fully fledged graf squad to keep pace with the rampant crews, whose burgeoning membership meant they were capable of producing huge full-colour ‘pieces’ (short for masterpieces) or mural-sized ‘productions’. As in-fighting between London’s graffiti kings escalated from merely ‘lining’ through or ‘dogging’ rival pieces to all-out violence and eventual arrest, famous crews like World Domination (WD), the Subway Saints (SBS) and Drop the Bomb (DTB) began to fracture and splinter. Many of those London pioneers went on to paint legal commissions and are at the heart of today’s scene, although the average street artist may be too young to have paid serious dues as an illegal ‘bomber’.

Although this history suggests that there will always be a steady stream of teenage boys who feel compelled to spray their immature artistic seed across any available vertical surface, it doesn’t explain why graffiti has now reached such dizzying heights of popularity and acceptance. Perhaps it’s because the emerging generation of artists is less concerned with painting illicit and illegible pieces for the benefit of their tiny community than with attaining wider fame and bigger audiences. Perhaps it’s because they are no longer constrained by the medium of spray paint on walls and are now incorporating all kinds of street furniture – from signs to statuary – into ad hoc installations, impulsive public interventions and increasingly political statements. Either way, the widening of the term graffiti to encompass street art, urban art and any other vaguely yoof-ful combination of art and adjective you can think of has led to an avid market for these previously unobtainable works.

As contemporary art is experiencing such unprecedented prices, it’s natural that street art is gaining value, especially among a generation of people who have grown up viewing it as art rather than vandalism. Luckily for the budding enthusiast, most collecting revolves around relatively cheap limited editions of bold, graphic images that can cost as little as £50. However, buyers should beware: the business side is still under-developed, so print editions are often too numerous to be likely ever to attain much value.

If history really is repeating itself, then the London graffiti scene will crash and burn as the New York one did after the ’80s art boom. In which case, it’s possible that only a few devotees will continue to make serious work and street art will go back underground, but the sophistication of today’s artists makes it more likely they will be around for years, perhaps even crossing over into the respectability of museum collections and art history books. Maybe journalists can finally stop looking for Banksy and start searching out the next unsung urban pariah-turned-poet. Check out our names to watch.

More art features

Discover Time Out original video