London has seen no shortage of Impressionism exhibitions in recent years. Do we need another? Possibly not. But this one does offer the chance to see some magnificent paintings from the collection of arts patron and Impressionism superfan Oskar Reinhart for the first time outside of his native Switzerland.

And the Courtauld Gallery is the perfect host, thanks to the many overlaps the collections of Samuel Courtauld and Reinhart, two men fascinated with Cézanne, van Gogh and Manet. This leads to some very literal parallels: for example, two Honoré Daumier paintings depicting Don Quijote and his groom, Sancho Panza, hang on opposing sides of the same wall, one in the permanent collection and one in the temporary exhibition.

The exhibition starts with a punchy trio. Immediately, you’re confronted by Goya’s ‘Still Life With Three Salmon Steaks’. Painted during the Peninsular War, it’s shot through with violence: against a stark black backdrop, the vivid pinks of the meat are almost unbearably fleshy, streaked with blood that pools at the base of the steaks. Goya, who masterfully depicts nightmares in his black paintings, here grounds his horror in the gut-churningly real. The effect is intense and bodily.

‘A Man Suffering From Delusions of Military Rank’, by Théodore Géricault, is a deeply unsettling portrait, part of a group of works thought to depict individuals with mental illnesses. Here, a gaunt man wears an approximation of military dress (a hospital ward tag hanging from his neck stands in for a military medal), his shifty gaze fixed on something beyond the frame. Géricault depicts him with care and sensitivity, but there is still something troubling about observing a man who is so lost to the world. Gustave Courbet’s ‘The Wave’ rounds out this intense start to the show. Made using a palette knife in place of a brush, there’s an immense solidity to the crashing wave and an oppressive weight to the purple bruised clouds above.

This is some truly impressive work from some of the world’s best-loved artists

From here, things slowly start to get breezier. The dappled sunlight of Renoir’s delightfully gossipy ‘Confidences’ shows the artist’s masterful command of light, but it’s his ability to anchor the whole painting around a single glinting diamond on one of the subjects’ fingers – rendered here with just a flick of white – that is most impressive. Claude Monet’s ‘The Break Up of Ice on the Seine’ is a wintry predecessor to his later ‘Water Lilies’ series, closely followed by a couple of lively Paul Cézanne landscapes that transport the viewer to the artist’s native Aix-en-Provence.

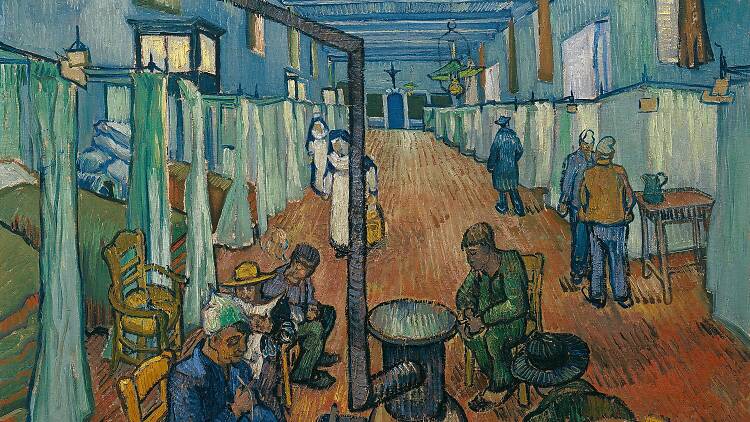

From van Gogh, we have two paintings depicting life in the hospital at Arles where he was admitted after attempting to cut off his ear. There’s a maddening claustrophobia to both, and a detachment in his depiction of the other figures (largely patients and nurses) with which he populates these spaces. Towards the end of the short exhibition, I found myself hugely struck by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s ‘The Clown Cha-U-Kao’, in which a female performer from the Moulin Rouge poses with a confidence Rosie the Riveter would envy, radiating an easy masculinity.

So, do you need to see another exhibition focussing on Impressionism and the artists who prefigured it? That’s for you to decide. If the answer is yes, don’t expect to come away with a fresh take on the movement – that’s not what this is. What you’ll find instead is some truly impressive work from some of the world’s best-loved artists – and that’s not to be sniffed at.