There’s a limit to how much you can say about Francis Bacon; to how many times you can talk about viscerality, the anguish of existence, the torment of love, etc etc etc, over and over. But we’ve apparently not reached that limit yet, because the National Portrait Gallery’s put on a big show of Frankie’s portraiture, and someone’s got to tell you if it’s worth 23 quid.

Francis Bacon (1909-1992) was a giant of modern art, maybe the twentieth century’s greatest painter. He’s been analysed and over-analysed for decades. It makes you walk into this exhibition (coming only two years after the Royal Academy’s Bacon show) and think ‘oh god, more Bacon? I’m already full, my cholesterol is going through the roof!’ Little bacon joke for you there.

But then you see the paintings – the writhing bodies, the contorted grimaces, the screaming faces – and damn it, call your cardiologist, you’re ready for another helping.

The show isn’t particularly well-organised , but it doesn’t matter. It starts with a pope and ends with a violent triptych of his lover George Dyer, and in between it journeys from friends to romantic partners to fellow artists and visions of himself. And the majority of it is stunning.

The opening corridors are filled with skeletal, corpse-like figures, shrouded in black and grey, locked in the cages he framed so many of his sitters in. Some are screaming into the void, others hang awkwardly in the darkness.

There are some rare, strange Bacons here. There’s a twisted multicoloured head in sunglasses that’s as psychedelic as it is morbid, a weird, sickly green homage to Van Gogh that looks like a terminally ill Christmas elf, an early Pope who looks like Speedy Gonzales in a fez, and two riffs on Van Gogh’s The Painter on the Road to Tarascon that reduce the main figure to an angry mess of shadows. Neither of those last two works is that great.

The last bit of the show focuses on those closest to him. His friend Henrietta Moraes is all sensual red swirls, fellow artist Lucian Freud is brutish and ape-like, the artist Isabel Rawsthorn is clear, confident, well-defined in a world of otherwise messy, complex, hazy painting.

But it’s the portraits of his lovers that hold the most tension and power. Peter Lacy is a large, imposing but fractured presence, while his last partner John Edwards is all smooth, young and pink. And then there’s George Dyer, the gangster boyfriend with whom he had a famously violent relationship. Dyer melts into a puddle of blood on a staircase, he wobbles dangerously on a barely balanced bike, and in the final triptych (depicting his final moments after overdosing in a hotel bathroom in Paris) he curls sickeningly around a toilet, nude and broken and sickly. It’s brutal, painful, too bare, too full of pain.

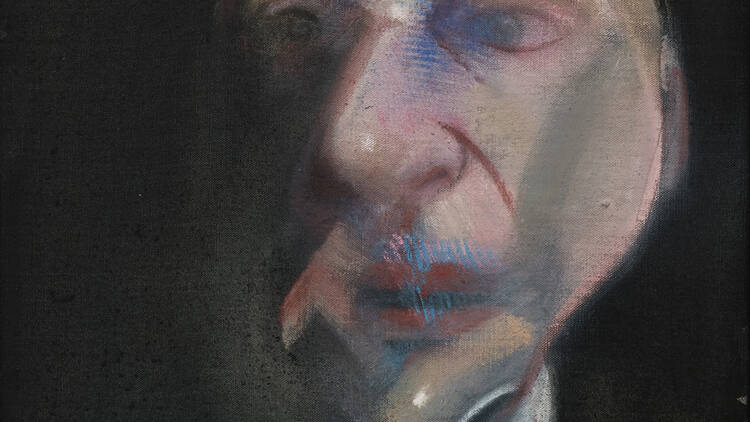

The self-portraits are maybe the least successful things here, other than that Van Gogh painting. They seem gentler, less incisive, weaker than his portrayals of others. Only the middle portrait in the study for three heads triptych (flanked by broken images of his recently deceased lover Peter Lacy) shows any bruising, angry insight, Bacon’s face bloodied and swollen

Do we need another show of this major artist’s work? Absolutely not. Could you argue that almost all of Bacon’s work is portraiture, making this show a little pointless? Totally.

But it’s Francis Bacon; you know the deal. It's full of viscerality, the anguish of existence, the torment of love, etc etc etc, over and over. It’s great.