Early photography can be hard to fathom, and not just because of all those people in top hats and capes trying and failing to keep still during ten-minute exposure times. The infancy of the medium in the 1830s is a confusing whirl of near-contemporaries, all messing about with lenses and chemicals in a bid to capture the fleeting world.

A matter of national pride, who did what, and when, is debated even today. France had Nicéphore Niépce who, as early as 1826 made a photographic image of his country estate using a camera obscura (a small wooden box fitted with a lens); Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, who gave his name to a new process of printing using light-sensitive, silver-plated copper; and Hippolyte Bayard who developed his own process and held the world’s first photo show in 1839.

On this side of the channel, we had gentleman scientist William Henry Fox Talbot, whose innovations with a negative-positive process were instrumental in creating images that were relatively light-fast and permanent. ‘Relatively’ is the operative word here; many of the images in this show are modern digital copies, the originals being too fragile to display.

Great storytelling in the early stages of this exhibition, which focuses on Talbot but includes examples by his European counterparts, gives a pacy account of these overlapping achievements. It’s science heavy (this is the Science Museum, after all) but also surprisingly poetic,with wall texts setting scenes such as the one in 1833 when Talbot, on the shores of Lake Como, wondered aloud how he might make ‘fairy pictures, creations of a moment… fix themselves upon the paper’.

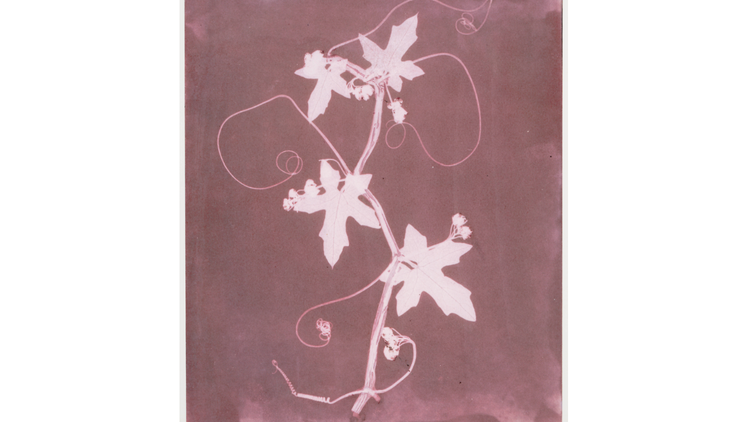

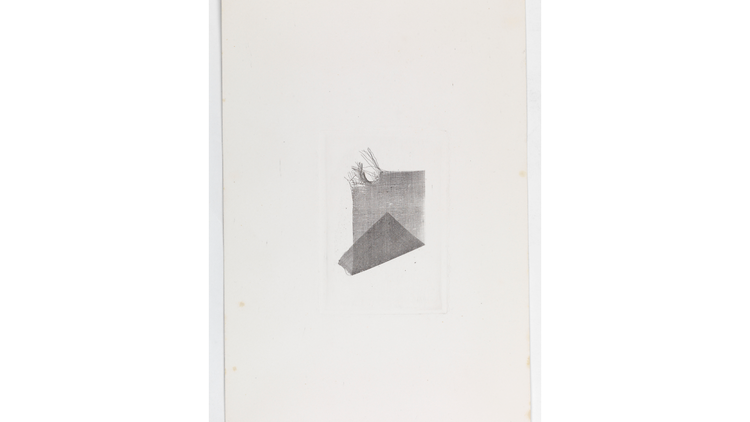

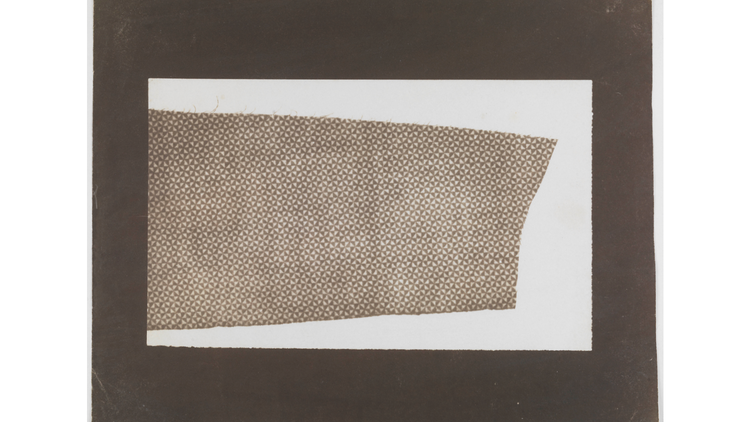

Back home, he started placing plants and pieces of lace on paper coated with light-sensitive silver nitrate, fixing the images with salt to create what he dubbed ‘shadow drawing’. By 1835, he was using a camera obscura to take images in and around his house, Lacock Abbey in Wiltshire. He photographed an oak tree, a footman, his half-sister playing a harp . He went on his travels, to Oxford, Scotland and, in April 1844, to London, where he shot some of the very first photographic images of the capital (‘Nelson’s Column Under Construction’, pictured).

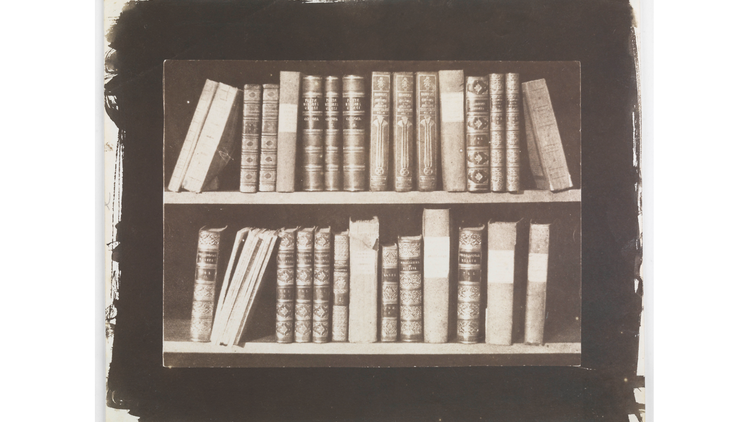

These are magical to behold. Even subjects as mundane as an open door or a bookshelf possess a kind of magnetism by virtue of being among the oldest in existence. That Talbot was a scientist rather than an artist, though, is borne out by the work in the latter stages of the show. More interested in the perfecting printing techniques, he started reproducing his own, much earlier images or borrowing those of others.

In a show of revelations, perhaps the greatest is that, despite its shadowy beginnings, photography’s practical applications – noble or otherwise – were illuminated almost immediately. As set out in his 1844 book ‘The Pencil of Nature’, Talbot identified that, in addition to taking beautiful pictures, you could catalogue your possessions (as evidence that could stand up in court) and copy important documents. Meanwhile, in Germany, Johann Carl Enslen was superimposing the face of Christ on an oak leaf, while in France, Hippolyte Bayard, miffed that Daguerre was getting all the credit, issued a photograph of himself as a drowned man with a suicide note on the back. Hot on the heels of the first photograph, it was the first photographic hoax. Which is the great thing about this show. While imparting loads of technical info about photography, it tells you even more about human nature.