Paolozzi wanted to produce art so badly that he faked his own madness. He was stationed on a Slough football pitch with the Pioneer Corps at the time, so who can blame him? Slough’s loss was the world’s gain: without Paolozzi there would be no pop art, and no vibrant mosaics at Tottenham Court Road. The Whitechapel had a serious challenge on its hands with this retrospective: the man defies categorisation. He moved from painting to collage to textiles with the pace of a crazed polymath. And so the exhibition moves chronologically, from the rough-hewn sculptures of the 1940s through to the abstracted screenprints and public art installations of the ’80s and ’90s.

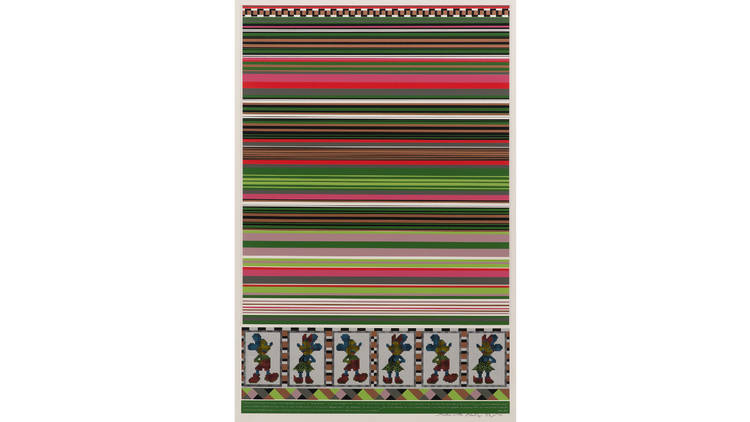

He was known to be easily distracted. While working, he would flip from one image to the next, frantically trawling advertisements and magazines. In his famous ‘Bunk!’ lecture, which is part-recreated using wall projections for this show, he presented clippings of Coca-Cola adverts, ’50s pin ups and sci-fi illustrations, analysing their artistic merit. These were the founding days of pop art, when it still offered a scathing comment on consumerism, before itself becoming commodified and losing all meaning. Exploring Paolozzi’s early work is a depressing reminder of how derivative this genre has become. In the giant, colourful ‘Whitworth Tapestry’ he weaves a silhouette of Mickey Mouse, a motif now so overused in commercial art we barely bat an eyelid when we see Disney characters surrounded by penises and swastikas.

On the second floor, we step into a blackened room for ‘The Silver Sixties’ era. Around this time, he began to focus on aluminium sculpture, which explains why this part of the exhibition looks like Cee Lo Green’s next Grammys outfit. It’s also when Paolozzi’s friendship with JG Ballard had begun to develop, each sharing a fascination with the relationship between man and machine. For Ballard, it materialised in his techno-porn novel ‘Crash’, for Paolozzi in his collection of screen prints, which are filled with cross-sections of the human form flanked by nuclear warheads.

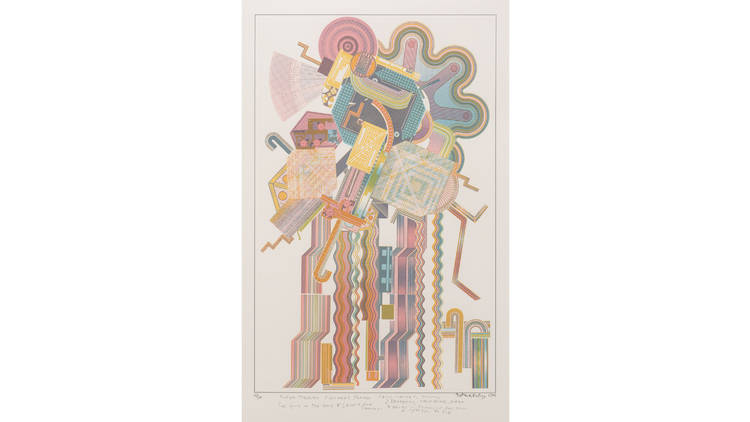

The final room leads you right into his disgruntled-old-artist era, when he turned his back on pop art, producing work that took intentional potshots at Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. Paolozzi attacks himself in the piss-take too, but it has that sad feeling of a journalist sarcastically retweeting criticism of their own work. You never really believe he includes his art in the fall from grace. This peevishness moved him to create ‘Calcium Night Light’, a lively series of prints inspired by the composer Charles Ives. The Whitechapel has curated this beautifully, flooding the room with music to complement the synaesthetic shapes and colours.

Towards the end of his life, Paolozzi donated much of his art, which is why so many of his sculptures can be enjoyed by the public across London: he was determined not to be forgotten. After this retrospective, he can rest easy. We’ve finally got a sense of the man behind the tube mosaics.