Heads up: this is a difficult show. It’s difficult because it documents in crisp detail some of the most shameful aspects of humanity over the last 60-odd years. It’s difficult because a lot of the images here were commissioned by newspapers and magazines to show their readers those shameful aspects of humanity, and were never meant to be coolly appraised in a big art gallery: they were meant to be spattered with the cornflakes you’d just choked over. And it’s difficult because it’s long and tiring, and you might feel a bit differently about yourself if – as I did – you skipped some photos of Bangladeshi cholera victims and starving Biafran toddlers because you needed the loo.

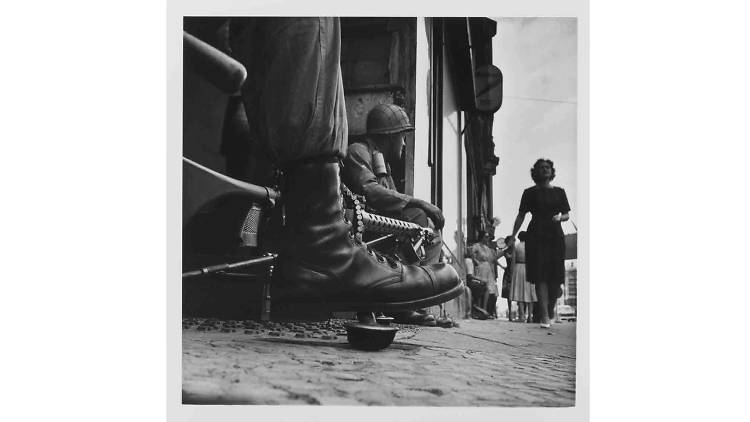

I’m being glib: it’s a defence. Over his career, Don McCullin has photographed things most people don’t want to think about, never mind see. Bloody, foul, repellent conflicts in The Congo, Cyprus, Cambodia, Nigeria, Northern Ireland, Vietnam and Beirut. Many of his images are iconic: his ‘Shell-shocked US Marine, Battle of Hué’ (1968) is a defining image of twentieth-century warfare, not just of Vietnam. McCullin helped invent the war photographer cliché that’s used to sell SUVs and beard trimmers – a modest non-combatant superhero, risking his life to bring you the TRUTH. Hell, there’s even a Nikon camera of his here that took a bullet for him in Cambodia.

Don’t get me wrong: McCullin is a magical, intuitive photographer. Almost every picture here is beautifully composed, lit and shot. It’s just hard to look at them objectively. They’re part of our shared understanding of history: they’ve helped create what we think history looks like. On the strength of that alone you should see this show, because it will make you question what images are for (and probably what human beings are for). McCullin admits that he has become ‘accustomed to the dark’. His pictures of non-warzones – the East End, Bradford, the North East – still look like warzones: desperate people in extremis. A homeless man raving against a backdrop of shattered Spitalfields buildings in 1970 is as bug-eyed and dehumanised as any Vietnam PTSD case. McCullin prints his photos very dark. A pall hangs over his view of humanity like the smoky factory clouds in his pictures of the north. There’s no escape from its shadow. Maybe we need McCullin to be a ‘legend’, to be extraordinary, so that the things he’s seen and recorded in his life can be the exceptions, not the rule. Trouble is – on this evidence – there’s an awful lot of exceptions.