The Qing Dynasty was massive. In every way. The final dynastic era of imperial China (which itself stretched back to 200 BC), its Manchurian overlords presided over a landmass bigger than almost any empire in human history. At one point a third of the world’s population was contained within Qing borders. It went on for hundreds of years. It’s synonymous with creativity, inexorable decline, civil war, modernisation, nationalism, visual art, drugs, cooking and language. Massive.

Too massive to cover in a show like this? The British Museum thinks so. That’s why it’s focusing on the final, climactic century of Qing rule. The country had just experienced the marathon tenure of legendary conqueror Qianlong and, unbeknownst to the people, it was all about to get messy. As China hurtled towards the revolution that would create a nationalist government (that would in turn cause the revolution that would create the Chinese Communist Party) every facet of life entered a state of flux. This exhibition is an attempt to show the afore-mentioned ‘every facet of life’.

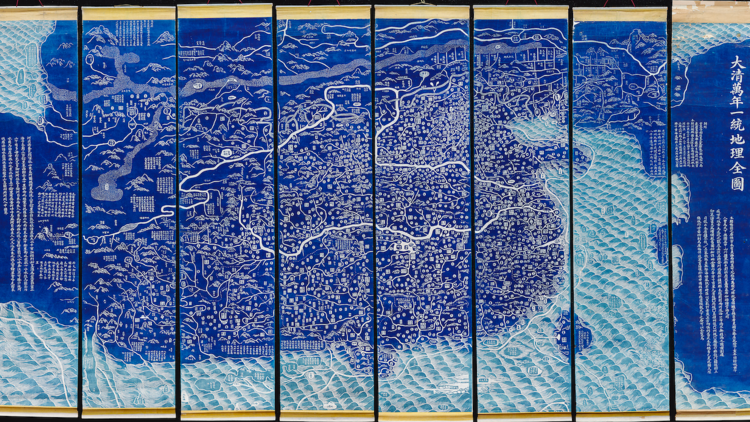

A relic of awe-inspiring potency if ever there was one

Does it succeed? Well, loads of what’s on display is great. You’d have to be brain-dead to not be impressed by the eight-foot dragon-y vases, gifted by the final emperor Puyi to George V on the day of his coronation. Or indeed, the outfit for a child, complete with a fish-dragon hat, designed to keep evil at bay through sheer psychedelic weirdness (seriously). Homeware covered in the mind-bendingly proto-modern ‘bapo’ graphic design style? Sensational. Best of all, maybe, is the Empress Dowager Cixi’s vivid, peacock-and phoenix robe, a relic of awe-inspiring potency if ever there was one.

Ultimately though, despite the hundreds of eye-catching, fascinating objects on display, it’s just not entertainingly presented. The organisers are also understandably keen to shine a light on social groups that flew under the radar (that is to say most social groups at that time). But doing it via the audible ‘thoughts’ of fictional archetypes feels cloying and a bit pointless. Combined with the fact that there’s no room to properly flesh out world-shaping events like the Taiping Rebellion, the Opium Wars and the Boxer Rebellion, it all ends up feeling quite slight. Which is weird for an exhibition with such big goals and so many lavish showpieces.

There’s definitely enough here to satisfy. It’s just a shame the exhibition lacks the depth, vividness and volatility of its subject matter.