Bridget Riley will make your eyes hurt and your brain ache. With her perception-altering lines and colours, it’s like the octogenarian grand dame of op art is reaching into your skull, grabbing a fistful of your optic nerves and twisting, pulling and yanking them in a million different directions.

Art, at its most basic level, is about looking. An artist uses pigments and shapes to create images which trigger recognition in your brain. ‘That’s a bowl of fruit,’ your brain says while looking at a drawing of a bowl of fruit. But Bridget Riley wanted to push that much, much further. What if the image didn’t just enter your brain, but messed with it, affected it, manipulated it. In the op art (short for optical art) movement she helped pioneer, paintings and viewers weren’t placed in a passive, one-way relationship, but in an undulating dialogue where the more you look the more you see, and the more you see the more you question what you’re seeing.

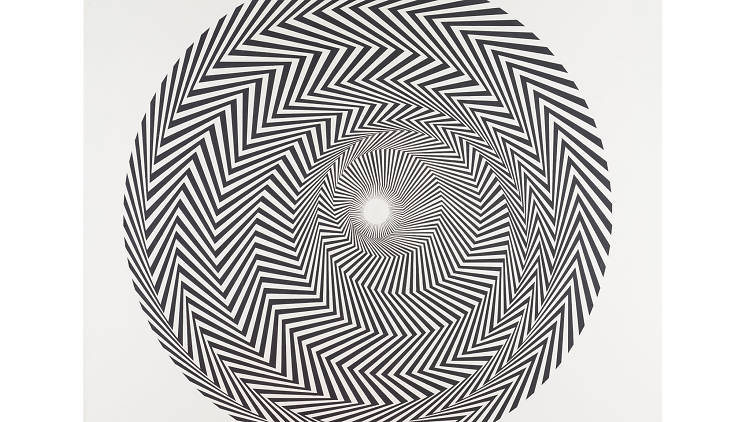

The best room in this show is filled with early black and white paintings and works on plexiglass. They’re the purest and most extreme expressions of Riley’s ideas. Thick squares squash down into little rectangles, sucking you into an infinite horizon. Circles fade into nothingness, straight lines curve into waves that your eyes just can’t latch on to. Everything tingles and wobbles, drifts in and out of focus, the picture planes jiggle and reform. It’s art as non-Newtonian fluid. Solid then liquid and back again.

It’s all about contrast. Riley messes with the space between the colours and the lines until the paintings come alive with vibration.

That’s the trick she’s pulled throughout her career. In the late 1960s, she created massive panels of straight lines of contrasting colour. Without curvature, it’s the clashing hues that set your eyes thrumming.

Upstairs, she combines colour and curve to even greater effect, creating these terrifying images that seem like they’re bulging out at you.

A lot of the more recent work is painfully dull – the colours and curves replaced by muted tones and ultra-formal composition – but after decades of innovation you can forgive her for slackening the pace a little. At its best, though, this is a beautiful show of stunning art by a vital figure in art history. It’s a celebration of perception, a chance to totally lose yourself in the act of looking, and the perfect opportunity to let Bridget Riley take your eyeballs for her ride. It’s more than worth the headache.