[category]

[title]

Review

Chew it all up and spit it out, that’s what the Brazilian modernists did. In the early twentieth century it was a country shackled by artistic conservatism but bursting at the seams with vibrant indigenous and immigrant cultures, so the modernists decided to gorge themselves on ‘cultural cannibalism.’ It’s a term from the writer Oswald de Andrade’s ‘Manifesto Antropofago’, urging artists to ‘devour’ other influences in order to spit out something new and totally Brazilian.

That new Brazilian cud is on display here, and it’s gorgeous. The 10 artists in this show mash together indigenous aesthetics, art history and influences from the new European avant garde with a social consciousness and desire to address the challenges of life in Brazil. Poverty, racism, immigration, radicalism and more colour than your eyes can handle.

Not that Brazil in the 1910s was ready for it. The first artist here, Anita Malfatti, was so hurt by the critical reaction to her big debut show that she largely turned away from progressive art afterwards. Her paintings from that era aren’t great, it’s the work of a young artist just starting to make experimental in-roads, not much more, but it shows you what kind of environment modernism was emerging into.

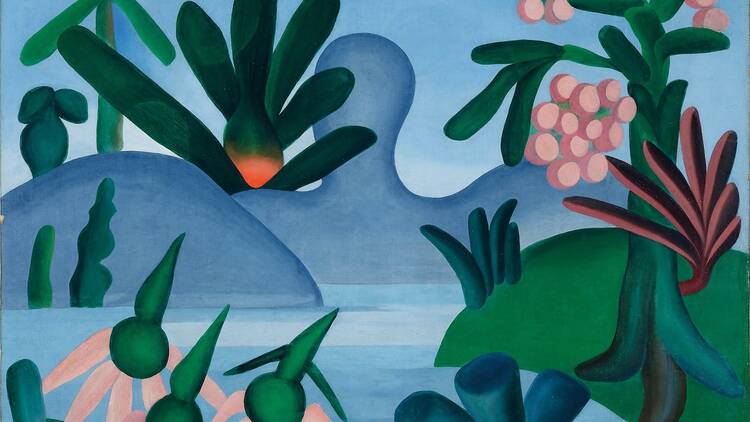

Laser Segall, a Jewish immigrant from Lithuania, fares better with his bright depictions of farm workers and mixed-race locals in dense jungle foliage, but the first real wow moment comes from Tarsila do Amarak. Her ultra-colourful, ultra-flat visions of towns and markets and landscapes are incredible: simple, direct, totally minimal, modern paintings of Brazil.

Stunning, almost psychedelic brightness

Djanira da Motta e Silva took a similar approach, but focused more on the people than the land. She paints kids flying kites, celebrants in Afro-Brazilian religious rites, workers toiling on coffee plantations, all with stunning, almost psychedelic brightness and incredibly bold, flat, simplicity.

Everyday Brazilians appear in the decidedly more bleak work of Candido Portinari too. Out in this vast country’s wild outback, the settlers and migrants and workers are malnourished, destitute and desperate.

The influence of Brazil’s indigenous population is maybe the most striking thing here. Vicente do Rego Monteiro combined Fernand Leger-esque figuration with nods to the ceramics and crafts of pre-colonial societies into dusty, dark slices of modernism.

Then Rubem Valentim amps up the colour. His geometric compositions are filled with references to Candombele deities, creating abstract totems for a new, spiritual Brazil. They’re so good. Not bad for someone who started out as a dentist.

There are some very dodgy paintings here, and plenty of artists have been left out of this supposedly definitive telling of this particular part of art history (Raven Row’s excellent recent ‘Some May Work As Symbols’ took a more diverse approach to the same topic). But there are also more artists here, and more approaches and ideas, than this review has space for. Chewed up and spat out by voracious artistic cannibals, Brazilian modernism is one delicious mouthful.

Discover Time Out original video