How long can you pump out the same ideas before anyone cottons on? In the case of British sculptural megastar Antony Gormley, the answer, apparently, is indefinitely.

We’ve had decades of bodies from him, plopped on buildings, whacked on beaches, shown in galleries and museums, some made of steel, some not, some cast and realistic, some splintered and geometric, but all basically the same thing; a human figure, based on the artist’s own tall, lean frame, repeated endlessly, plonked everywhere.

And here at White Cube, on an impressive scale, is more of the same. The first Gorm is made of flattened rolled steel, a group in the next room – pressing their heads against the wall like they’re as bored of this as the rest of us – is made of thick bars of oxidised cast iron, a giant in another room is made of huge blocks of metal. Gormley’s use of his own body as a symbol of universal experience is problematic in itself, but the real issue is the relentless repetition of the same artistic trope for decades. Even if it was once a good one, it's been worn out through overuse. It’s boring, weak art that only means anything to the billionaires who use it to decorate their sprawling gardens.

They’re at once terrifyingly claustrophobic and alluringly safe

But there is at least one new idea here, though it’s hard to tell if it’s actually good, or just good because it’s different from all the other guff. Lining the central corridor of the gallery is a series of single-occupant concrete bunkers, each a different contorted bodily shape, a single air hole left open where the mouth should be. They’re at once terrifyingly claustrophobic – these dense, suffocating tombs – and alluringly safe; spaces where you could survive almost anything if you could just find a way in. They’re solitary, paranoid things, a balm against a deeply threatening world.

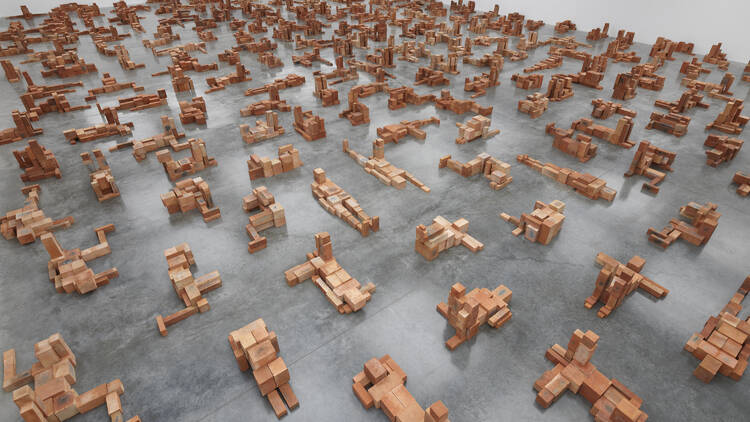

In the final room, a vast field of bodies is made of precariously balanced bricks. They lie supine or collapsed against the wall. Are they corpses washed up on a beach, abandoned on a battlefield? There’s violence and death here in either case. Though maybe that's a generous interpretation.

These last two works feel like Gormley looking a bit beyond himself, thinking of the wider issues of humanity – death and destruction in an age of tension – instead of just his own body and ego.

There are some good ideas here. Let’s hope he doesn’t just rehash them for the next three decades.