Artists aren’t widely known for inventing things of practical use. Things of beauty, yes, but something you might wind up buying in a shop, carting home and assembling with the aim of making your life easier? Believe this show’s publicity, though (and there’s no reason to dispute it) and American artist Alexander Calder (1898-1976) is the man responsible for distracting restless babies and relieving dog-tired parents the world over by inventing the mobile.

Calder, of course, wasn’t the first person to hang bits and bobs from wires and sticks and let them dangle in the breeze. Wind chimes have been around since prehistoric times. The earliest suspended toys demonstrating the planetary system date from the eighteenth century. Strung-up kinetic sculptures were even being created by radical artists such as Alexander Rodchenko, Naum Gabo and Man Ray in the 1920s, a decade before Calder set his art works shimmying into life, first with the aid of motors, then through the interaction of air currents on metal shapes suspended from axial beams, rods and strings attached to the ceiling. But, he was the first to give to his inventions the term ‘mobile’ – and to make exploring their possibilities his life’s work.

And the results are utterly, endlessly entrancing – as effective, it turns out, on an audience of adults as infants. There’s delight from the off. First you’ll see Calder’s whimsical, riotous wire works from the 1920s, essentially drawings in space, including a strongman, lithe dancers and acrobats, and caricatures of fellow artists Joan Miró and Fernand Léger miraculously given substance by the white wall against which they’re shown.

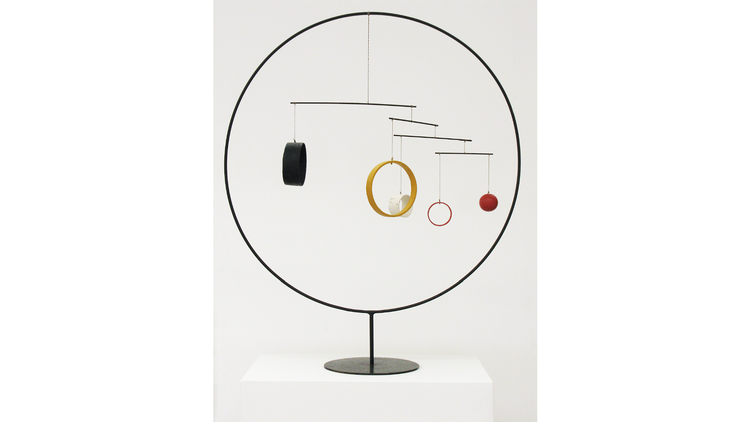

Next come his experiments with motorised sculptures from the 1930s – coloured spheres and discs attached to lengths of wood, wire and pulleys so that when activated they rise and fall, cross like hands of a clock or shoot off comically, like early imaginings of space travel (Calder anticipates the spiky look of Sputnik-era design by decades). Where once you could have given them a crank and set them into juddering life, too fragile to move they are now immobile, redundant – although you can see them in action on tiny screens.

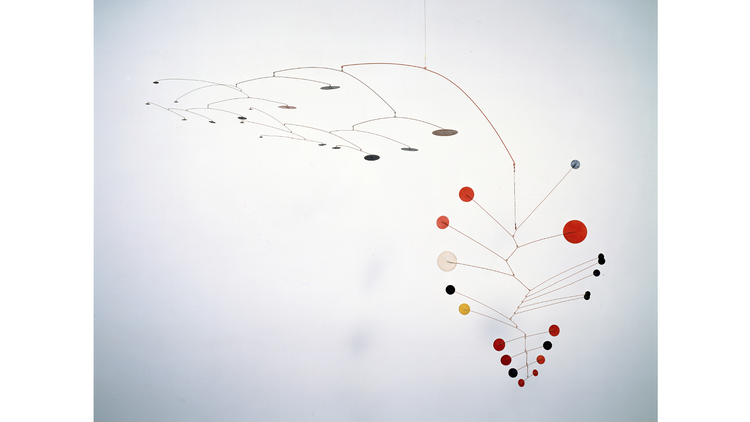

In this sense, the show takes a while to really get going. Its highpoint, though, is worth the wait. Lots of artists at the time were ‘releasing’ sculpture from the plinth. Calder’s contribution was not just to remove his art from its pedestal but to set it in motion, so that it happens in real time and keeps on happening every time it’s caught by the current from an air vent or a moving body (this must be the first show at the Tate with a notice telling you not to blow on the art). It reaches a majestic crescendo in a room that brings together 16 mobiles – variously bringing to mind biplanes, birds’ wings, branches and skeletal fish – are disturbed by the slightest draught or current while, impeccably lit, they draw you into interweaving shadows on the floor, ceiling and walls.

There’s an argument being made here that the trembling, delicate qualities of Calder’s best work are partly also the reason why he is considered something of a modernist lightweight (levity and joy not being high on an art historian’s checklist for greatness ). But it’s clear that Calder was a mover rather than a shaker. A trip to the studio of Piet Mondrian converted him to abstraction. In fact, the word ‘mobile’ was suggested by his mate, the conceptual art daddy Marcel Duchamp. And perhaps because his own work explores its relatively narrow concerns so exhaustively, he has few artistic heirs, no art movement to his name.

Still, it hardly matters when the work recalls natural phenomena as magical as flocking starlings or the first flurry of snow. Looking at Calder is one of the most singular experiences art has to offer. It’s captivating. And way too good for just babies.