After decades of high profile dust-ups with the Chinese government and continued exile from his homeland, Ai Weiwei is a household name – more famous than his artworks. A big clap, then, to the Design Museum for this strong exhibition mixing old and new works by the dissident artist. ‘Making Sense’ is coherent, purposeful and serious; and concise enough to act as a useful primer for anyone wanting to put a few artworks to the name.

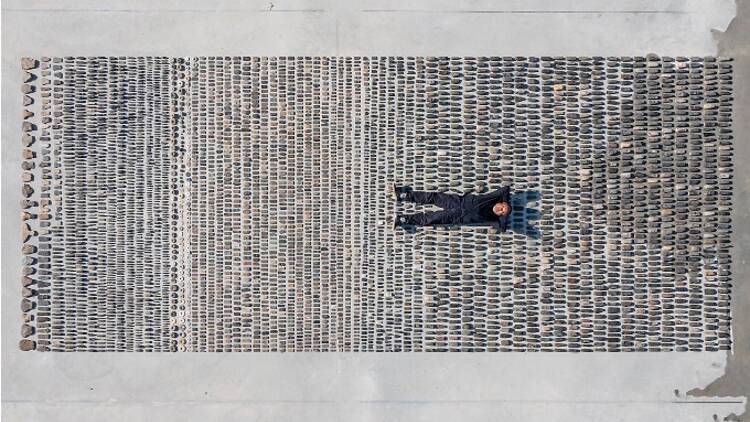

‘Making Sense’ is all about construction: its building blocks, its victims and its ultimate erosion at the hand of time. Staged in one open plan space, the show’s conceptual groundwork is laid out in big grid-square installations that cover the floor. Oldest is the grid of neatly lined-up hand axes, both beautiful objects and essential technology for the early humans violently reshaping the environment of Stone Age China. Next, heaps of wonky teaspouts, rejected by some long-ago Song Dynasty quality controller, piled up here by the artist in a heap of broken shards, all curvy and jagged like discarded human bones.

On the surface all is as tranquil and organised as a rock garden: the porous textures, the pale palette of ochre, pink, brown, greige and green. Dig deeper and there’s a more troubling story. Take the beautiful ancient porcelain balls used as ammunition, and piled chunks of Ai Weiwei’s own pottery, smashed when the Beijing government destroyed his studio. These carefully arranged collections of fragments are framed on violence, coercion and bureaucracy. They are diagrams of the eternal, ongoing handshake between construction and destruction, tools and weapons, beauty and power.

Around the walls the same story is told deftly in mixed media and garish colours. There are hours of video footage from Beijing, the artist driving through jerry-built houses and narrow streets, many of which have been knocked down in the two decades since. A sombre collection of over 5000 names individually stamped on paper commemorates schoolchildren who died in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, many in poorly designed and cheaply constructed schools.

Dig deeper and there’s a more troubling story

It’s not all doom and gloom. I giggled at highly coloured new versions of the artist’s 'A Study In Perspective', photos where he sticks his finger up at various iconic buildings like the Houses of Parliament, Eiffel Tower, Trump Tower and similar. They’re not new but they feel at home here in this space and this show. Anyone can join him in his life’s work of sticking it to the man by sharing their own finger filp in the crowdsourced version.

For a small-ish show in a small-ish space this has real and impressive heft. That’s partly because of the years of magpie-ish collection and conservation that has fed Ai Weiwei’s installations. The ‘wow’ piece here is a 15-foot long reproduction of Monet’s water lilies, constructed out of Lego. It’s art for a digitised age: weird, troubling, beautiful and provocative. Amazingly, this plastic remix – known as 'Water Lilies #1' – takes one of the most cliched teatowel-ready images in the art shop and makes fresh, almost casually authoritative post-modern art with it. Look at the Lego water lilies from a distance and the bricks seem to disappear; it's misty, muted, mysterious. Look closer and the Legos appear; they are like pixels but physical, 3D, tangible. There’s an emotional depth to the work that comes from touchability and from the hours of work by hand. And of course from the legend of his own lifetime: among the lilies is a 'dark portal' representing the door to the dugout where the artist lived undercover with his exiled father in the 1960s. Undershadowing the brightness of his celebrity is the moral courage and sheer persistence that it’s taken for him to be an artist, and specifically to become the artist known by so many as Ai Weiwei.