Feet off pedals, I zoom downhill, braking on occasion to better savour the scenery flashing by. Near-vertical banks of hillside flank the road – bursting with greenery, cascading purple flowers and waterfalls. And to think, this exquisite landscape is just a bonus. The real reason I joined this bicycle tour is to explore the tulou – the iconic rammed-earth fortresses that punctuate the countryside in the southern Fujian province.

Built by the Hakka and Minnan people between the 12th and 20th centuries, these impressive, multi-storey complexes and the traditional, communal way of life practiced by the people living in them managed to survive China’s great bulldozing over the last few decades thanks to their remoteness and the mountainous geography surrounding them.

A Unesco listing in 2008 and new highways in recent years have brought busloads of visitors to the most famous of the tulou, but hundreds more remain well off the tourist map. Located down dirt pathways inaccessible by car, these dwellings are best reached by bike. But with decent maps hard to come by and few signposts – with any wrong turn potentially adding additional, arduous ascents – this can be a challenge. Fortunately, our group has a pair of excellent guides. We are led by Bruce, a Hong Kong-based Aussie, who uses his killer sense of direction to shepherd us through mazes of tea and sweet-smelling tobacco fields. It helps too that he’s been visiting the area for eight years. He is joined by a local guide, Liz. With Liz around to translate, we are asked inside for tea with such regularity that we find ourselves having to turn down every other invitation.

Historically, the residents here would not be so hospitable to outsiders. Each tulou was like its own fortified city, designed to keep intruders out. Their rammed-earth walls stand up to five stories high and two metres wide – thick enough to resist cannon fire. Within these walls, storage rooms for stockpiling, wells, and expert pickling skills (still evident in the local cuisine today) allowed the clan members inside to survive a siege.

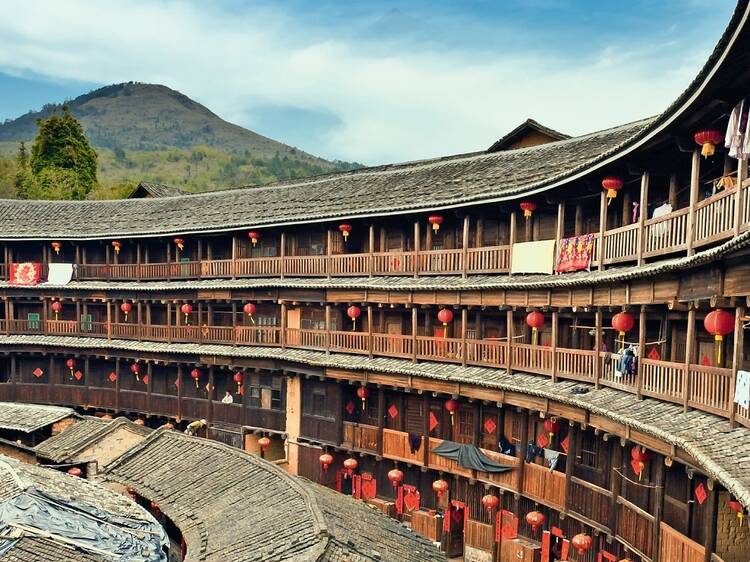

Many of the tulou are doughnut-shaped, with circular, wooden balconies enclosing an open-air courtyard in the middle like London’s Globe theatre. But instead of seats for the audience, the balconies lead to rooms. On our first night we stay in one of the more unusual ‘phoenix-shaped’ tulou, in a Unesco-listed cluster in Hongkeng village. From the outside it looks like a rectangular mansion. Inside, balconies look out onto a warren of buildings with tiled roofs reaching up to different heights. A woman leaning out of a window at the top of a thin tower brings to mind that scene from ‘Romeo and Juliet’.

In this atmospheric setting, complete with red lanterns, I get chatting with one of the residents. Like everyone else living in this particular tulou, he’s surnamed Lin. He tells me they are all part of a single clan. At one time, 27 families, comprising some 200 people, lived in this one building. Today they are down to 60 residents, with many of the rooms now rented out to travellers. The advent of tulou tourism has been a mixed blessing. On one hand, it’s helped provide work and reasons for the young to stay on, instead of abandoning their communities for the lure of China’s boomtowns. In the Unesco-listed areas, there has been greater incentive to repair historic structures instead of tearing them down to make way for modern, identikit, white-tiled homes. And yet, alongside preservation, the bump in visitor numbers has brought change too.

During a pre-breakfast stroll alongside the river that runs through Hongkeng, we have the sights mostly to ourselves. But on the way back, we see evidence of the village gearing up for the arrival of crowds of day-trippers from the city of Xiamen: stalls stockpiled with tobacco pipes and mini tulou in snow globes.

No such knickknacks are present at the communities we visit later in the day. We reach these tourist-free clusters by going off-road on our bikes. We wind along bumpy gravel tracks, stopping to snap photos and drain our water bottles, slogging up then rushing down hills. As we pass by slopes lined with tea bushes, the air is so thick with their scent that it feels as though we’re steeped in it.

We’re thrilled to be invited into an old couple’s abode: a ground-floor room inside a grand, round tulou. As we drink cup after cup of Iron Goddess Oolong, I take in the simple surrounds. The bare white walls are decorated only with a poster of Premier Xi Jinping. Later, we spot a myriad of Mao Zedong murals on crumbling walls. Perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising that Communism proved popular here. For the better part of the millennium proceeding Marx’s manifesto, the residents of the tulou were already living as a community of equals. They farmed collectively and rotated household chores. Kitchens and bathrooms were shared; all the bedrooms were the same size and style. Instead of allocating different floors according to social hierarchy, each individual family would own one vertical column, with the eldest members residing on the ground level and the youngest sleeping at the top.

Today, as many of the young leave for the comforts of city life, traditional practices are fading. Many of the less-accessible tulou we visit are almost abandoned; only a handful of pensioners dozing in doorways remain.

My legs are groaning from cycling over 90km in two days, but I’m happy that I’ve been given a glimpse into this unique world before it disappears entirely.

The author travelled on The Hutong Fujian Tea & Tulou Eco-Cycle Weekend Getaway. Departures are scheduled throughout the year; see www.thehutong.com for more details. Guide Bruce Foreman also organises bike trips elsewhere in China – see www.bikeaways.com for more information.

Discover Time Out original video