Into the void

The stagnant, greasy air is broken with a sharp warning from a man with a walkie-talkie: ‘No, no, no. Itu tak boleh.’ He points at the camera in my hand.

The short ride up was shared with a woman dressed in a black skirt, a pink top and thick make-up. The lift opens – the number of the floor is simply scribbled on the wall with a pencil. She leads her customer by the hand, a young lad barely 20 years of age, into one of the units down a desolate corridor lined with red stains from the steady stream of betel nut spit. All the units are secured with padlocked metal grilles.

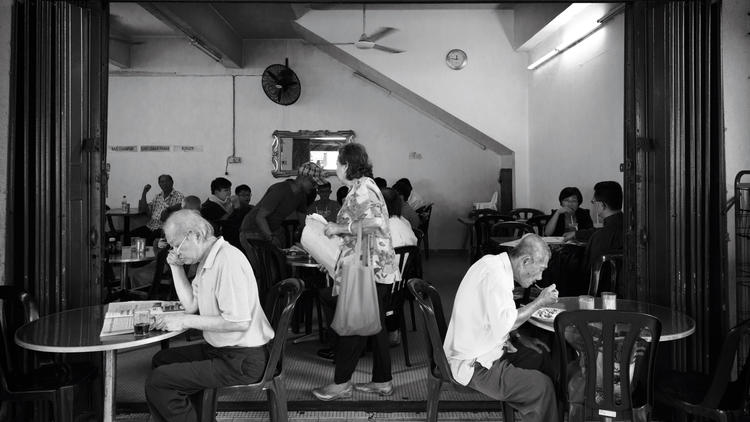

We arrive at the end of the corridor. The unit is shared between two refugee families – mothers look after the children while the men toil away at work, some scraping away dried cement under the scorching sun at the construction site of a luxury apartment while others try their best to memorise the words of the menu at a food court. We see them around us all the time, but we don’t usually remember or think about them.

‘It’s harder for the men. They have to leave the house to work. Anything can happen to them. We just sit at home and take care of the children. We don’t dare go outside.’

The house is bare without any furniture or electronics. A single square window affords them a view of the chaotic Pudu wet market. The Petronas Twin Towers and the KL Tower in the distance fit perfectly between my thumb and index finger.

The Chins are the largest group of refugees from Myanmar in Kuala Lumpur, running away from persecution and hardship. The majority of them, housed in cramped apartments in areas like Pudu, Cheras and Bukit Bintang, arrive in Kuala Lumpur with dreams of being resettled and literally beg their way into menial jobs. Without legal recognition as refugees, the lucky ones get registered at the UNHCR; the even luckier ones struggle to earn a decent living while they wait, many of them for years, to be resettled in the United States, Canada or Australia.

Tracing our way through the corridor and back to the lift, I walk past another woman leading an old man into one of the units. Back on the ground floor, I shift to the side as the man with the walkie talkie ushers a long queue of eager customers into the lift.