The 1970s

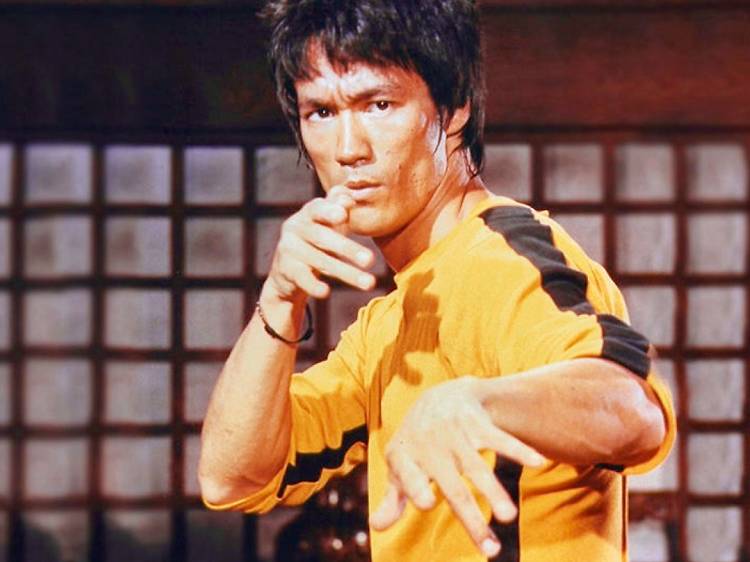

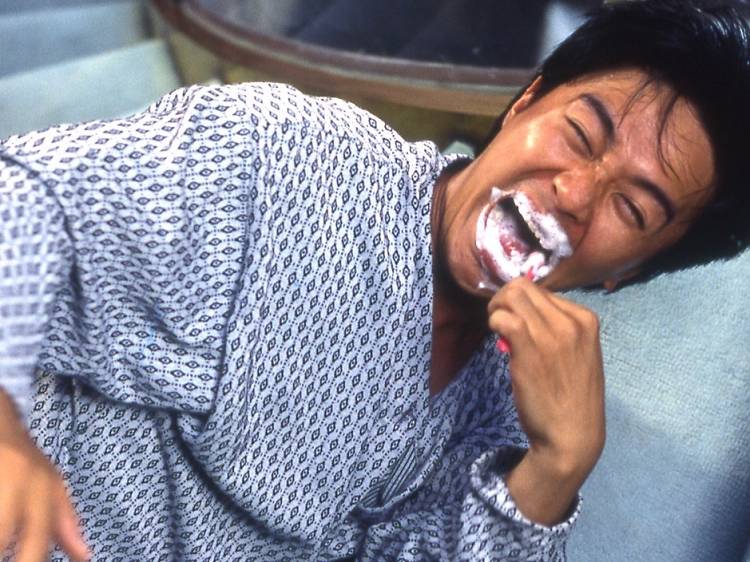

Hong Kong cinema started to come of age in the 1970s. The decade began with Bruce Lee and his fists of fury exploding onto the big screen in 1971 in The Big Boss. Sadly, just two years and three films later, he had passed away. Iconic as Lee was, it was actually 1973’s The House of 72 Tenants (pictured) which was to prove the most defining film of the era. Throughout the preceding decade, production of Cantonese films had plummeted from 211 releases in 1961 to just one in 1971 as Mandarin productions, perceived as more sophisticated, dominated. A riotous Canto comedy, 72 Tenants set new box office records – breaking those recently set by Lee – and confirmed the language of ordinary Hongkongers as the language of the city’s cinema.