Dressed from head to toe in black and donning a pair of tinted glasses, African American artist Mickalene Thomas’ appearance is in stark contrast to her works presented at Central’s Lehmann Maupin gallery – colourful, complex, collaged and filled with patches of glimmering rhinestones. The Desire of the Other is Thomas’ first solo exhibition in Hong Kong. As a queer woman of colour, she finds a lack of representation in Western art history as her inspiration for creative expression. Drawing from French impressionism, the American’s impressive body of work examines concepts such as beauty, sexuality, gender and race.

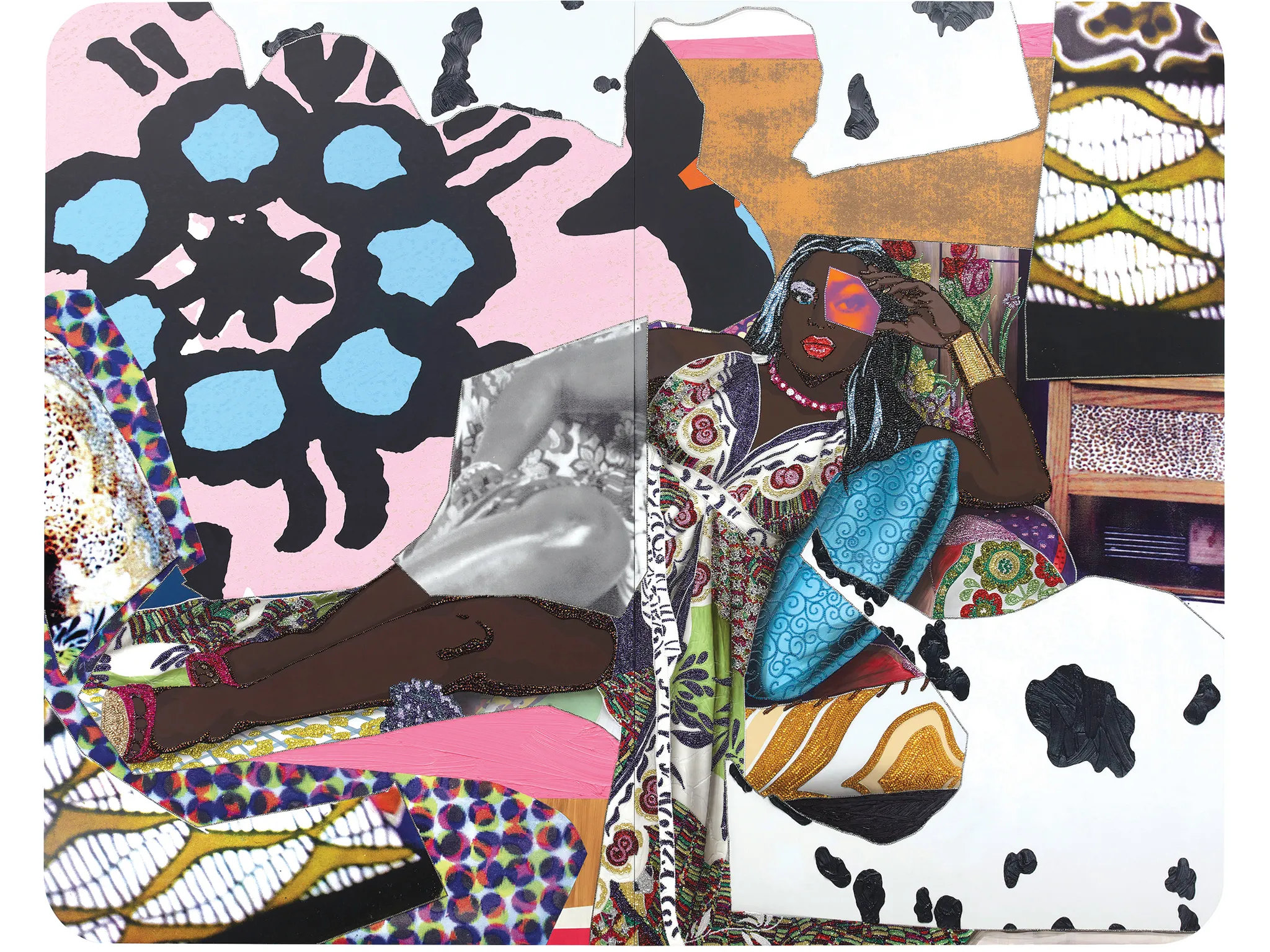

“I’ve always wanted to understand why particular notions like beauty and sexuality in our history are not evident in art history,” says Thomas. “When you saw women of colour in Western art, they were always in servitude positions. They were put in our peripheral. They were never uplifted or perceived as these notions of beauty.” Portraying and depicting women of colour through positive imagery, Thomas’ portraits are collage paintings built from a mix of photographs – that she has taken or collected – acrylic, enamel and, her signature, rhinestones. Presenting seven representative paintings in Hong Kong, including three large-scale canvases, these works are all connected, despite coming from different series and threads of work. All seek to explore common notions of beauty. With racial issues as salient as ever, Thomas believes that the representation of African Americans is required and that painting ‘black sexy women’ is needed as an act of defiance. She talks us through her creative journey and inspirations.

“Growing up,” recalls Thomas, “art, in most African-American communities, is never necessarily something that you ascertain as a career. Art was always something that you did, not something you made a career out of.” Born in New Jersey and growing up in Portland, Oregon, Thomas was exposed to an arts education very early on in her life thanks to her mother. She and her brother would attend after-school programmes at Newark Museum and the Henry Street Settlement in New York. But it was a photography exhibition, Carrie Mae Weems’ Kitchen Table Series at the Portland Art Museum in 1994, which captured scenes of African-American families, that was a pivotal point for Thomas and inspired her to become a visual artist. “It was one of the first times I saw a contemporary artist’ work, of a woman of colour in a museum of that calibre,” states Thomas. “[The photos] really hit a chord with me. To understand that you can have these powerful images in art, and what that could do to be transformative. To be inspiring and political and familiar. From that point, I knew that’s what I wanted to do.”

Thomas made the decision to enroll at the renowned Pratt Institute back in New York for her undergraduate studies and went on to attend the even more prestigious Yale School of Art afterwards. Through her studies, Thomas was introduced to French impressionism and pointillism and eventually drew inspiration from artists like Matisse, Édouard Manet and Romare Bearden. “My attraction to French impressionism was through my interest as an artist of incorporating what was considered a high art and a low art,” says Thomas, “and how you bring those two worlds together. How do you bring the aesthetic of what was considered outsider art into the foreground.” Thomas also cites Manet, in particular, as an inspiration in finding a platform to reclaim agency for women as opposed to being depicted as an object in the background. “Manet was a revolutionary of his time,” Thomas claims. “The act of creating and using women that were considered lower class in his work was very provocative and painting them as beautiful women made people start responding to and wanting to emulate him. Those artists were butting against a particularly sociopolitical regime of their time through their art.”

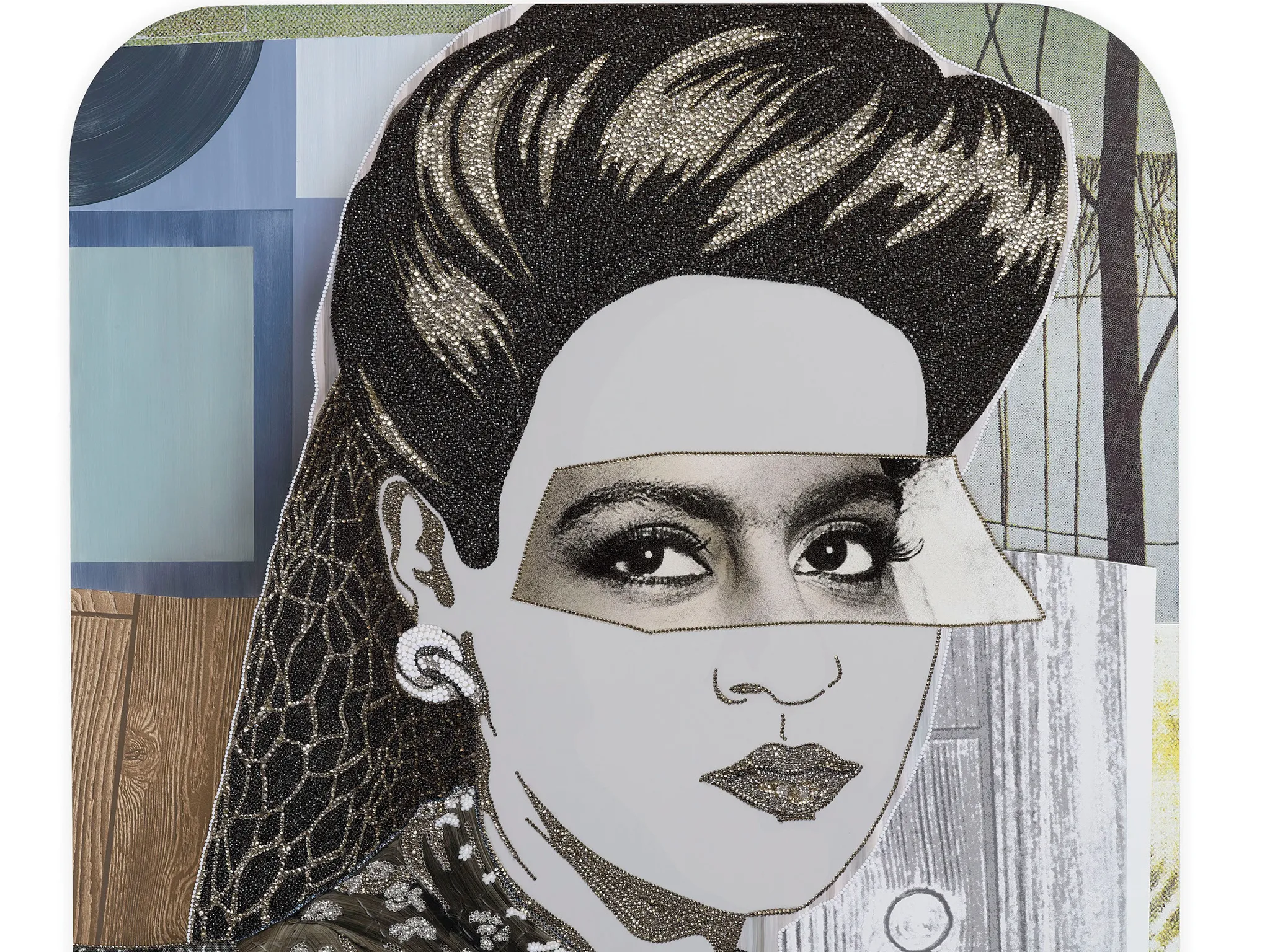

Following in the footsteps of these historical artists, Thomas strives to challenge traditional notions of beauty, femininity and race. “The images that I’m pulling from historically are about capturing the gaze,” she explains. “The eyes are what is so prominent about a Mona Lisa painting.” With her love of collage, Thomas effectively draws the viewer’s gaze to the subject’s eyes by replacing them with a cutout piece of a photograph. Stepping back, viewers can see the rounded corners of the canvas on these portraits, which acts as an invisible frame, reminiscent of old photographs. But, more importantly, the women in Thomas’ work are portrayed as confident and entirely comfortable in their own skin. “Varying sexuality is a way of giving the women that I work with agency,” Thomas states, “giving them that space to claim and assert themselves, creating a platform for them to deliver the prowess and letting them have this opportunity to reside in a space for understanding their beauty and sexuality. And it’s not necessarily a negative thing for a woman to own that. It’s a celebration, for me as a woman of colour, to put these images out there as a way of allowing others to see themselves.”

Her body of work also doesn’t shy away from sexuality, often portraying women in provocative poses. But, to Thomas, sexuality does not equal confidence. She tells us: “People use sexuality to mask themselves as confident women and the need for women to do that is to serve the pleasure of men. We have to own our own understanding of our sexuality because we live in a world where our sexuality is defined by the male gaze. Our sexuality is also defined by a woman’s gaze, of how we see ourselves in each other.”

Thomas’ signature incorporation of rhinestones in her paintings is also an exploration of artifice, the use of beautification to present ourselves differently to others. “The use of rhinestones is layered with meanings about how we adorn ourselves,” she explains. “They’re decorative notions of how we have the need to pose, how we mask and present ourselves. Adornment can have a positive and a negative connotation but we as a human race look at ourselves through others. There’s a need to beautify ourselves. And people of colour always have to do it.” Combining all these elements, these paintings are both visually captivating and socially and politically provoking.

In light of the recent American presidential election, the changing political landscape and deteriorating race relations in the US, it’s as important as ever for Thomas to paint and portray women, especially women of colour, in a positive light, much like the portrait she did of Michelle Obama back in 2008. “I thought she’s a very classy, smart, beautiful black woman,” she says. “And there were very few images of Michelle Obama at that time. I thought, ‘how amazing to have that representation in America, especially for the children in school’.” Moving forward in a society that has normalised discriminatory and prejudicial rhetorics, Thomas is determined to continue her work and the impact it creates. “One has to step back to figure out a way to position themselves so that their voice can be heard,” she says. “It’s not necessarily about being reactionary but being proactive and realistic. First and foremost as an artist, it’s important to allow people to be transformed, to come in, see work and ignite something in them. Allow them to feel good about themselves.”