The history

In 1920, British Hong Kong defined neon signs as electrically-charged glass tubing "with neon, argon, helium or other inert gas" in the signage law. Back in the day, folks didn't keep their eyes glued to mobile devices and instead, would look up and about, seeing things at the tilt of their heads. Neon signs were means of advertisement, and the most visible ones were often earmarked by people to communicate their locations.

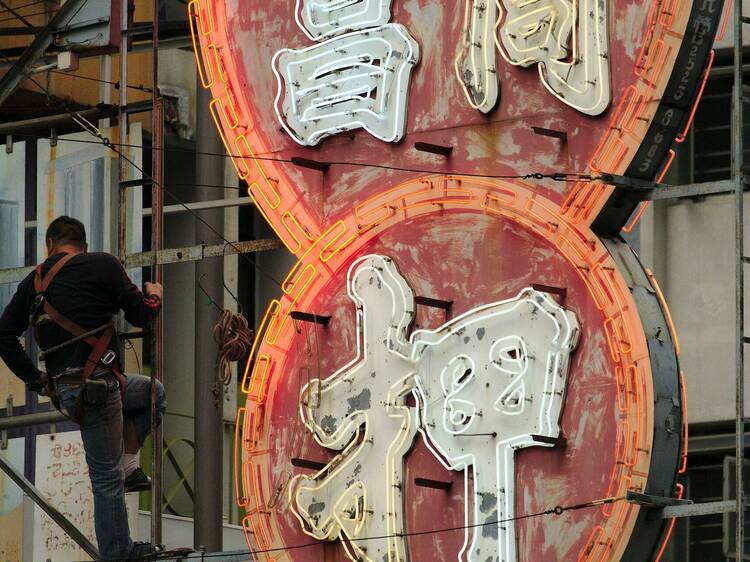

Hong Kong's neon age boomed between the 1950s and 1980s, lending the city its electric, eternal glow. Spanning multiple stories, the National Panasonic on Nathan Road used to be one of the world's largest neon boards during the 1970s. Pulsating beams in different colours, the heyday of neon light coincides with the city's golden age. However, the tide started to turn in the 1990s when LED emerged as a more energy-efficient option. Shopkeepers swapped out neon signs to cut costs, and the neon business rode off into the sunset.

For public safety, Hong Kong's Validation Scheme for Unauthorised Signboards went into effect in 2013, which mandated the removal of all unauthorised signboards. The number of signboards in Hong Kong, together with the neon ones, was estimated at about 120,000 in 2013. Between 2018 and 2020, more than 2,000 signs were forced out of the city's streetscape, counting over 760 signs in Yau Tsim Mong District alone. As if that wasn't enough, the Minor Works Control System deters businesses from commissioning new neon signs with higher costs and extra red tape, accelerating the disappearance of neon signs.

Against that backdrop, urban development and gentrification were (and still are) also underway to push away old shops. Traditionally, a sign is an integral part of a business, sometimes passed down the line as an heirloom. When businesses can't withstand the changing tides of time, their cultural riches disappear along with their shining legacy, the neon signage being one of many.