This review is from the Soho Theatre in London, earlier this year.

What responsibility does an artist have to the people whose stories they tell? It’s an old question, but one that’s sharpened in recent years, especially in relation to marginalised voices. Kieran Hurley’s clever, compassionate play cuts to the heart of the matter. This is a story about Libby, a depressed, middle-class, middle-aged Scottish playwright, who overcomes writer’s block through co-opting the voice of Declan, an anxious, impoverished, working-class young man with a talent for drawing.

Orla O’Loughlin’s production was first seen at the Traverse in Edinburgh last year – a theatre which features in the play. Hurley’s prickly approach to metatheatricality is only slightly blunted by this transfer (Libby’s bitter speech about how brutal the London theatre industry may scrape a few bones). But it arrives with Kai Fischer’s instructive design – a big, imposing frame around the stage – and the original cast intact.

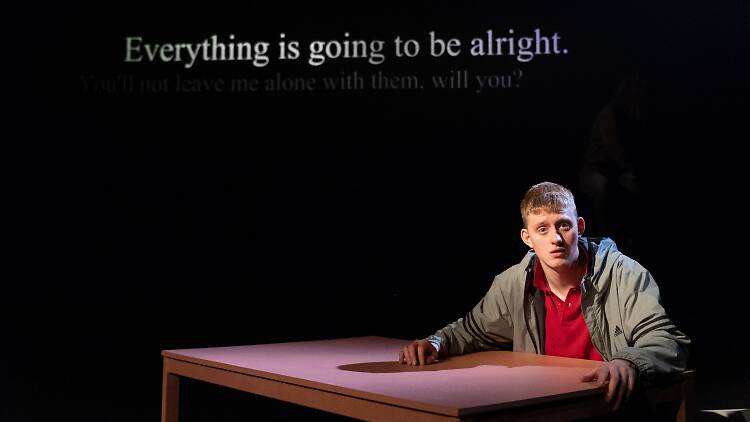

Neve McIntosh as Libby is gently believable as a lost soul in the grip of a mid-life crisis, even as she charts a somewhat extreme journey from a genuine determination to help Declan to cynically using him as mere material. And Lorn Macdonald is fantastic – very funny as the sarcastic, suspicious yet actually deadly serious teenager, the part glisteningly written by Hurley in swear-spangled dialect. Macdonald reveals Declan’s hard exterior is thin as an eggshell; inside, he’s fragile as a chick. There’s an ever-present risk that life will crush him.

Libby seems to offer him salvation through art – either via nurturing his own artistic talent for darkly brilliant drawings or through the play she starts writing about him. But Hurley doesn’t just make this an obvious, tragic tale of exploitation: throughout, ‘Mouthpiece’ explicitly reminds the audience of the expected, satisfying structures of storytelling. Libby periodically addresses the audience as if we were on some course about the rules of writing a play – where you need conflict, when there should be a reversal. So as the story moves through its inevitable highs and lows, we’re primed for them, and duly become more circumspect.

This gives the play a bit of a free pass for some of the more clichéd moments – as when the relationship lurches in a slightly-too-predictable direction – but it is also pleasingly subverted in the final scene, when the set notion of how a story must conclude becomes literally wrestled over by its characters. ‘Mouthpiece’ is heart-in-mouth moving, grimly exhilarating – giving us the juicy denouement we crave – while also smartly questioning why we want it in the first place. Life never gives us neat endings; people are infinitely more complicated and unexpected than they’re usually written, Hurley reminds us.

Basically, ‘Mouthpiece’ is a dream for the theatre nerd: it’s got heart, smarts, and something necessary and critical to say about both the artform itself and the unfairly unequal society we live in.