Whatever Bram Stoker might have led you to believe, Transylvania is not the natural habitat of the vampire. Blood-sucking demons hover far more frequently in the folklore of the Adriatic region than the misty-mountain environs of Count Dracula’s castle. It’s an aspect of Europe’s supernatural geography that 19th-century literary circles were well aware of – until the publication of Stoker’s genre-defining novel in 1897 suddenly sent everybody in the wrong direction.

The explosion of vampire literature in the intervening century has seen such an inflation of corpuscle-craving creatures that there seem to be few corners of the globe left without a colony of their own. Which makes it all the more surprising that the Croatian Adriatic has received so little attention. Thanks to a growing body of local researchers and writers, however, it seems that time is ripe for Croatia to regain its rightful place on the European vampire map.

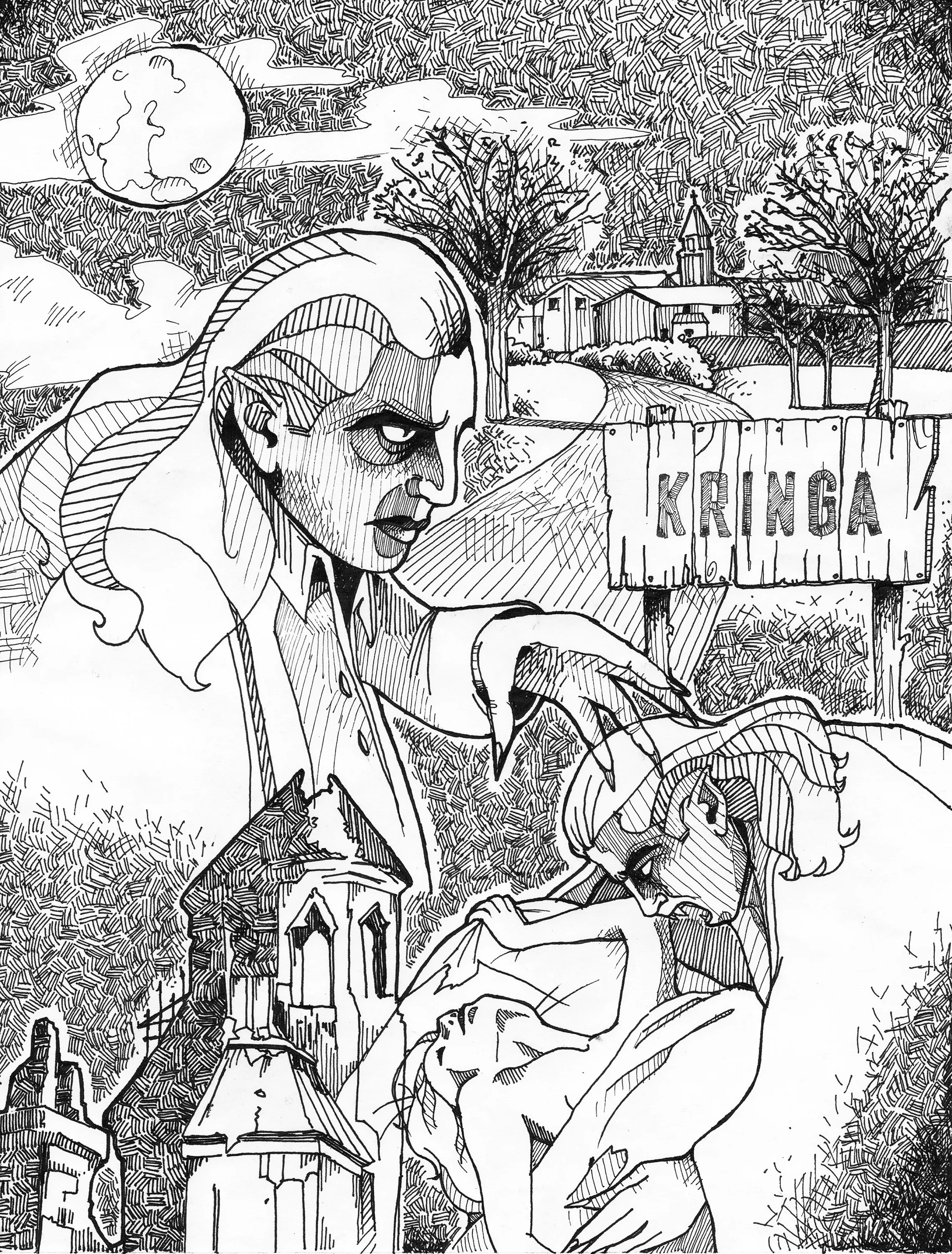

Standing at the centre of Croatia’s vampire heritage is the case of Jure Grando, a 17th-century farmer from the inland Istrian village of Kringa. An account of Grando’s beyond-the-grave antics was published by the Slovene geographer Janez Vajkard Valvasor in 1689, the first documentary reference to a case of vampirism in European history.

A huddle of stone houses squatting amidst lush green fields, Kringa is nowadays the peacefully rustic kind of place normally associated with farmhouse conversions, holiday rentals and cosy village inns. However Jure Grando has not been totally forgotten: caffe-bar Vampir in the centre of Kringa pays somewhat restrained tribute to the village’s most famous son, and the village graveyard receives a steady trickle of visitors – although Grando’s final resting place remains unmarked.

Valvasor visited Kringa only a few years after the Grando case and clearly spoke with villagers who remembered it well. According to Valvasor, Jure Grando died in 1656 and spent the next 16 years rising nocturnally from his grave, terrorising locals, and sharing the bed of his widow. Taking matters into their own hands, nine courageous locals dug up Grando’s body, drove a stake through its heart and then chopped off its still-smiling head.

The case contains all the archetypal ingredients that make up the modern vampire story. Indeed it is tempting to conclude that western culture’s image of the vampire – from Bram Stoker’s sexual predator Dracula right through to the turbulent teenage hormones of the ‘Twilight Saga’ – derives from Valvasor’s account of Grando.

‘Despite being set in Transylvania, Bram Stoker’s Dracula resembles Jure Grando much more closely than Vlad Dracul (the 15th-century Romanian prince) who allegedly inspired the story’ explains Boris Perić, the Zagreb-based writer who has become something of an unofficial spokesman for Croatia’s vampiric heritage since the publication of his own horror novel Vampir in 2006. ‘Transylvania was a dark and exotic eastern border’ Perić continues. ‘The location suited Stoker’s purposes even if the history didn’t.’

Perić’s own feeling is that Valvasor’s account of Grando found its way into the Western literary tradition via a somewhat roundabout route. It is known that Bram Stoker got many of his ideas from ‘The Vampyre’, the story begun by Lord Byron and finished off by his friend Dr Polidori when they were holidaying on Lake Geneva in the summer of 1816. The Byron-Polidori generation was in turn influenced by European folk tales of the supernatural collected by German writers; and one of the most frequently reproduced of these tales was Valvasor’s account of Grando, the bed-hopping demon from the Istrian village of Kringa.

For Perić, the key figure is Lord Byron: ‘The idea of the modern, literary vampire as a cynical, erotic individual was invented by Byron during that famous summer on Lake Geneva. It’s perfectly possible that the inspiration for this was Grando, the vampire who raped his wife – the similarities are too striking to be discounted. Polidori simply took Byron’s idea and finished it. Byron heard of the Grando case through German sources. His friend Matthew Gregory Lewis had travelled throughout Germany and had a good knowledge of the kind of folktales that were in circulation. The Grando story had become part of the corpus.’

Croatia’s claim to be the cradle of the modern vampire doesn’t just rest on the case of Jure Grando. Local folklore is full of references to the creatures of the night, from blood-drinking vampires (known here as vukodlaci) to nocturnal spirits called ‘more’ who visit sleeping humans and suck up all their energies – leaving them all clammy and exhausted in the morning. Eighteenth-century documents reveal that stories of the supernatural invoked tangible fear: officials from Dubrovnik travelled to the island of Lastovo in 1737 to stop the locals from exhuming the bodies of suspected demons.

Venetian traveller Alberto Fortis, whose ‘Voyage in Dalmatia’ was published in 1774, found that belief in vampires was widespread in the Adriatic hinterland. ‘When a man dies suspected of becoming a vampire’ wrote Fortis, ‘they cut his hams, and prick his whole body with pins; pretending, that after this operation he cannot walk about.’ Fortis’s contemporary Ivan Lovrić researched the subject at more length, reporting that the vampire of popular Dalmatian belief was very much a sexual predator. According to Lovrić, local women were ‘not ashamed to admit, that vampires had forced them to submit to their wishes. They are, it is clear, spirits who love adultery.’

All this had a significant effect on the European public, who began to associate the Adriatic coast with all kinds of mysterious practices and beliefs – vampirism among them. Travelling across the Lika in the 1870s, the British journalist (and future pioneer of Minoan archaeology) AJ Evans wrote that ‘every churchyard we pass is haunted by the ghostly creations of Slavonic and Oriental fantasy, the Vukodlaks or vampires’. It was only with the publication of Bram Stoker’s ‘Dracula’ that Transylvania became the newly imagined homeland of the lusty nocturnal demon, and the Adriatic’s role in the story was largely forgotten.

Forgotten, that is, in the rest of the world. Croatian folklorists never stopped researching popular tales of the supernatural, building up a large body of scholarship on the subject. It is the northern Adriatic regions of Istria and the Kvarner Gulf that have preserved most in the way of vampire lore. The publication of Istrian journalist Drago Orlić’s compendium of folk stories ‘Štorice od Štrig i Štriguni’ (‘Tales of Witches and Sorcerers’) in 1986 revealed just how many vampire narratives were still in circulation.

Central to Istria’s supernatural bestiary is the Štrigun, a creature that lives among humans by day and turns into a demon at night, bearing illness, sexual molestation and death. The Štrigun has a natural enemy in the shape of the krsnik, a human being who possesses sufficient supernatural power to battle the Štrigun and protect the community – Buffy the Vampire Slayer, your spiritual ancestors are here.

‘In Valvasor’s account of the Grando case, the men of Kringa send for someone from the nearby village of Lepoglav to help them with their vampire problem’ Boris Perić explains. ‘This is probably a reference to a krsnik. A krsnik is a member of the community, a bit like a shaman, whose supernatural gift is passed from generation to generation. They still exist in small numbers. It’s not difficult to see the krsnik of Istrian folklore as a kind of prototype for Dr Van Helsing, the vampire-hunting character common to modern literature.’

Jure Grando isn’t the only local historical figure to have exerted an influence on vampire fiction. The 15th-century Queen of Hungary, Barbara of Celje, had a reputation for cruelty and was known as the ‘Black Queen of Zagreb’ as a result.

According to Perić, ‘Barbara of Celje may well have influenced the author J Sheridan le Fanu, who published ‘Carmilla’ in 1872. An outbreak of tuberculosis in a village near Varaždin led to a legend that Barbara of Celje had risen from her grave to drink people’s blood.’

Many of these themes found their way into Perić’s novel Vampir, in which Jure Grando’s descendants visit present-day Zagreb. ‘I didn’t want the book to be simply a pulp adventure’ the author explains, ‘I wanted it to say something about contemporary society as well. After all Bram Stoker did the same, using the vampire as a way of dealing with sexuality – especially all those forms of sexuality not directly linked with human reproduction. It’s pretty clear that in my book vampirism can be read as a metaphor for capital. For me it was the ideal opportunity to write about today’s political and social rituals.’

So far Perić has resisted the temptation to write any sequels, although his interest in the supernatural has yielded some unusual literary fruit. His 2010 book ‘Na večeri s Drakulom’ (‘Dinner with Dracula’) is a stimulating collection of cultural and culinary essays that cries out (or should that be ‘bloodthirstily shrieks’?) for an English-language translation. For those of you who have always dreamed of treating your dinner-date to Bat Soup, the recipe is right here.