Olja Savičević Ivančević: ‘Rijeka is...a port, in every sense of the word, literally and metaphorically’

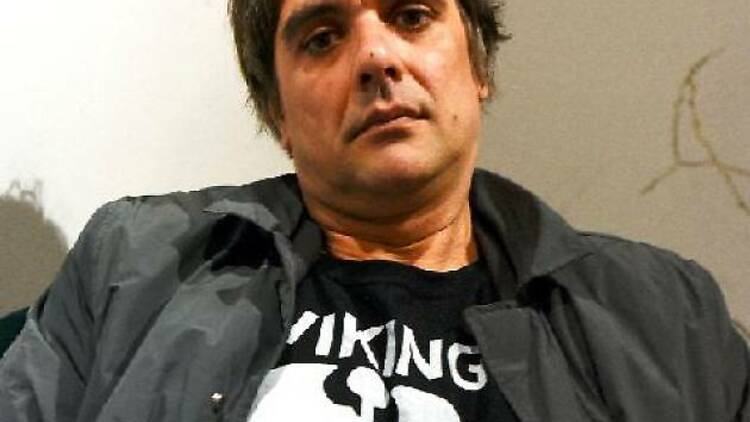

Olja Savičević Ivančević (43) is a writer, poet and journalist from Split. Her writing has been translated into over twenty languages. Her debut novel, ‘Adios, Cowboy’ attracted domestic and international praise. Savičević will spend her residency on the island of Cres, in the small village of Filozici, where she will work on her third novel.

‘Adios, Cowboy’ and ‘Singer in the Night’ are set in your hometown Split. Your work often dwells on the provinciality of Split. How would you compare Split to Rijeka, a city that has always been labelled as alternative in the cultural landscape of Croatia?

Split is a city that has an extraordinary identity, but it is also extremely bipolar - the best and the worst things in the city are taken to the extremes. Rijeka is also a city of a very expressive identity, but it doesn't have the same contradictions Split has – at least seen from the outside. It is a city that has a positive connotation to it, it is more liberal and more open-minded that our other bigger cities, therefore it's alternative.

Rijeka has a dominant European vibe, or at least an aspiration to be a modern city. I think that's the reason why the city attracts more and more people from the world of culture and arts.

But Rijeka is a much smaller city than Split or Zagreb…

Rijeka doesn't lack anything to be a big city besides more inhabitants. A larger number of people makes city a metropolis and creates a critical mass. However, even in our biggest cities in Croatia, there is a feeling of provinciality. In Split, six months per year, there is a large influx of people to the city, but when they leave, what is left resembles less and less to a city, and more and more a neighbourhood of touristic apartments.

Split is south and the sea, with its bright and dark side, Rijeka is rainy, and represents a different type of Mediterranean, it is a port. Split is pop and rap music, Rijeka is punk. As their name suggest even, Split is contradictory, divided, Rijeka (river in Croatian) is constant. Split is neurotic, Rijeka is melancholic.

The name of Rijeka’s 2020 program is ‘Port of Diversity.’ Can the city live up to this slogan?

The fact that it aspires to this slogan, means for me that Rijeka deserves it. In a country where the diversity is not welcomed - almost as if it were a swear word, to be proud of the diversity is a proof of courage and originality.