As we brace for the future, let’s reflect on the past.

The concept of the quarantine as we (all too well) know it today wasn’t always around.

History’s worst pandemic is thought to be the Black Death, which took between 75-200 million lives in the 14th century. As a desperate attempt to stop the spread of disease, the world’s first-ever quarantine was implemented in 1377. Its inventor? The Republic of Ragusa, one of the medieval Mediterranean’s greatest maritime powers. Today, we know the creator of the quarantine as Dubrovnik.

During a March 16 press conference, the World Health Organization’s general director Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus declared quarantining the currently ongoing pandemic’s best opponent. Ghebreyesus implored “…the most effective way to prevent infections and save lives is breaking the chains of transmission. And to do that, you must test and isolate.”

So what can we learn, if anything, from the history of quarantines in the city that invented them?

The world’s first quarantine

Dubrovnik’s response to the Black Death pandemic (1348) and other 14th-century plagues (1358, 1361, 1363, 1371, 1391)

At the beginning of the 14th century, Dubrovnik thrived, encompassing a city within its famed walls (which are popularly known as the setting of Game of Thrones’ King’s Landing) and its surrounding villages. Latin, Italian, and Croatian were spoken in the multinational republic, whose citizens enjoyed long-term economic and political stability. Trade and diplomacy flourished, the city’s harbor welcoming ships from near and far. Members of government were elected democratically and functioned within a General Council, Senate, and Small Council.

© Dubrovnik Travel

The Black Death struck Dubrovnik in 1348. 2,000-10,000 lives were lost in a matter of four years, out of a population believed to have numbered between 6,000 and 30,000. Two thirds of the republic’s citizens are thought to have perished.

Plagues had a cyclical nature during the Middle Ages. Famines followed sickness, as fields and livestock were left unattended. Hunger would then, due to malnourishment and weakened immune systems, again give rise to barely bygone plagues. Dubrovnik fought off rounds of ruin for years.

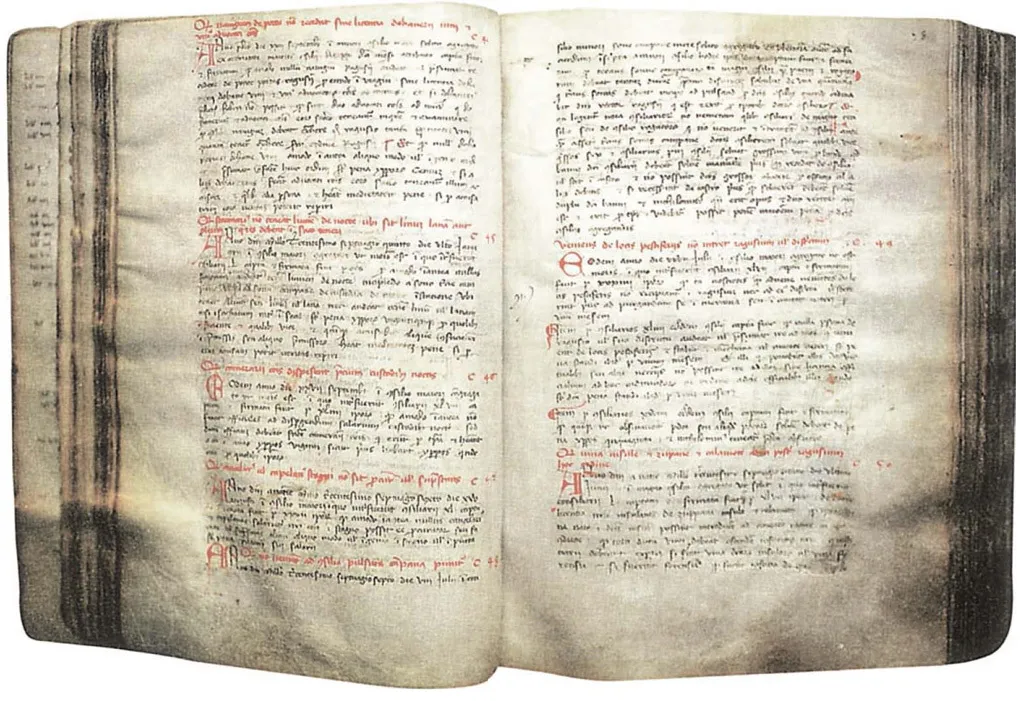

After three disease-ridden decades, the republic’s Great Council decided on July 27, 1377 to establish a quarantine system. It was the first of its kind in the world. Lawbook Liber Viridis (‘Green Book’) marks its inauguration, under a decree stipulating Neither local nor foreign peoples coming from infected areas will be admitted to the city or surrounding land until they’ve undergone a month-long cleaning on the islands.

Liber Viridis, Leges et instructiones, held in the State Archives in Dubrovnik

The new ruling sent travelers directly to the small, mostly barren islands of Bobara, Mrkan and Supetar and later Koločep, Lopud and Šipan, for 30 days. Occasionally, camps were built which could be assembled quickly and burned down just as fast if they became worn out or the plague passed. Often, however, those sent to the islands had nowhere to hide from rain, wind, cold or summer heat.

The Great Council added to the quarantine law in 1397. A new isolation length of 40 days was authorized. The initial, 30-day quarantine was dubbed trentine, but with the new 40-day regulation came a new name: quarantena. Punishments for disobeying were also defined and ranged from fines and jail time to draconic public shaming.

Quarantines and kacamorti

Dubrovnik’s response to 15th-century plagues (1400, 1416, 1422, 1433, 1437, 1456, 1464, 1473, 1481, 1486, 1491)

Plagues continued their recurrent nature into the 15th century, and so, the government of Dubrovnik continued to mandate quarantine measures.

An anti-plague hierarchy was organized in 1426. The General Council elected a new so-called Health Magistrate which consisted of five noblemen. The Health Magistrate commanded harbor captains, guards and kacamorti (from the Italian cacciare, meaning to catch, and morte, meaning dead).

Kacamorti duties included supervising quarantine lengths and keeping records of each ill person: when they fell ill, the address of their house and a list of their family members. Their work was demanding and dangerous. Kacamorti were appointed for a year at a time, with two new elected officers beginning their service six months before their predecessor's term end. The goal was to save training time, which was key to stopping spread of the plague.

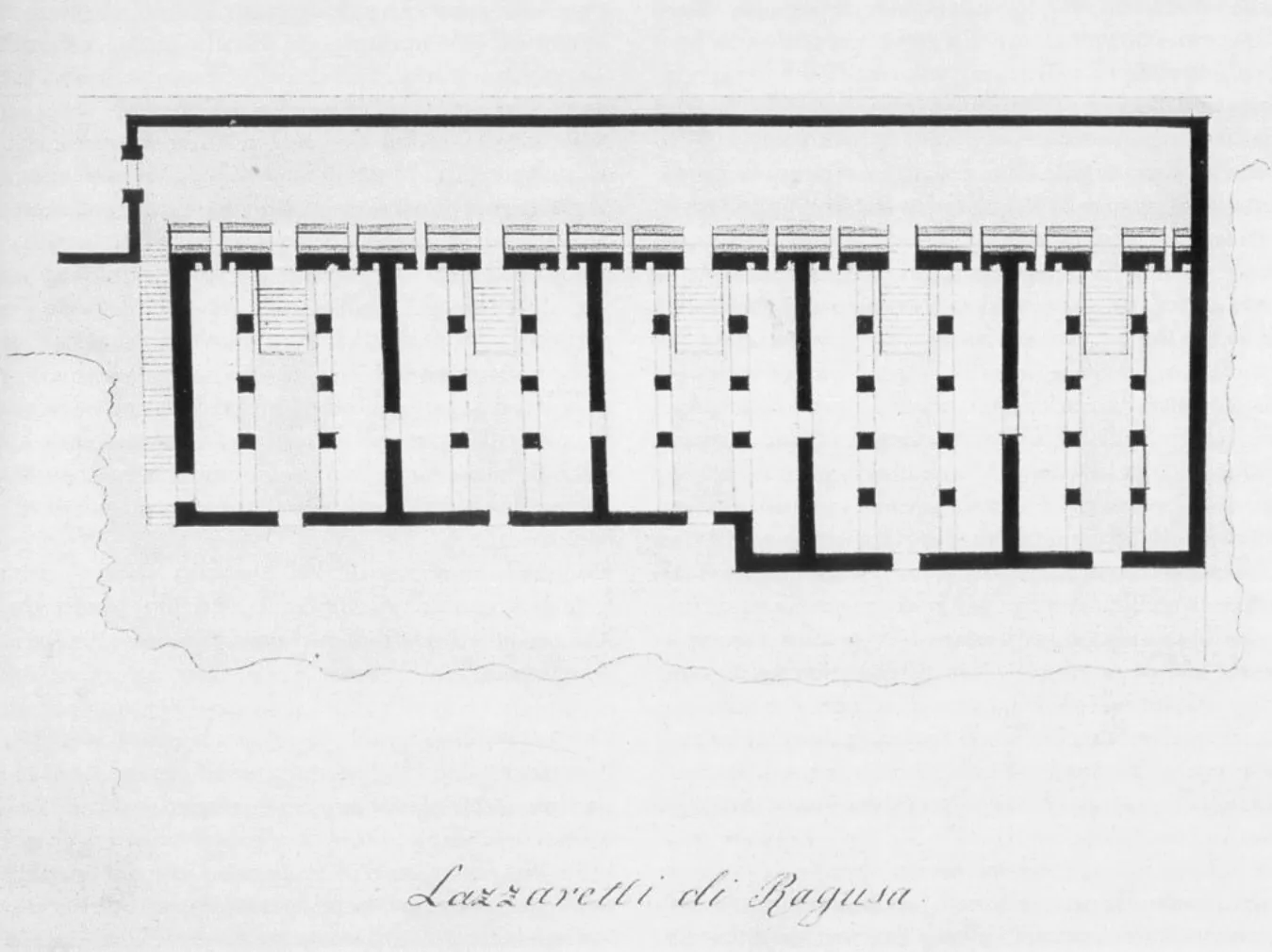

In 1431, the first stone lazzaretto (a building created to hold quarantined persons) was built on Supetar island for the ill and the suspect. The building was 10 meters long and 4 meters wide. Construction of additional, larger lazzaretti soon followed. By the mid 1450s, lazzaretti were fully equipped facilities, each with designated staff members including guards, gravediggers, cleaners, priests, and barbers.

From 'The Lazarets of Dubrovnik' by Zdenka Janeković Römer

Those who survived the plague were often subject to poor treatment from their family, friends, and neighbors. Carrying the stigma of having been ill wasn’t easily shaken. In a time where supernatural beliefs prevailed, illness survivors were deemed suspicious. Before having 21st-century medical knowledge, people wondered whether those capable of surviving such a lethal illness were demons.

Other major European centers adopted Dubrovnik’s example in the following decades. For example, Venice implemented a quarantine system in 1423, and their own Health Magistrate in 1486, while Genova implemented the quarantine in 1467.

Cultivating the quarantine

Dubrovnik’s response to 16th-century plagues (1500, 1517, 1526, 1533, 1540, 1572, 1583)

Another hard-hitting plague invaded Dubrovnik in 1526 for six months. During that time, trade completely stopped. The government banned members of the elite from leaving the city for their countryside vacation homes, attempting to cut off the spread. Punishment for disobeying was loss of status as nobility.

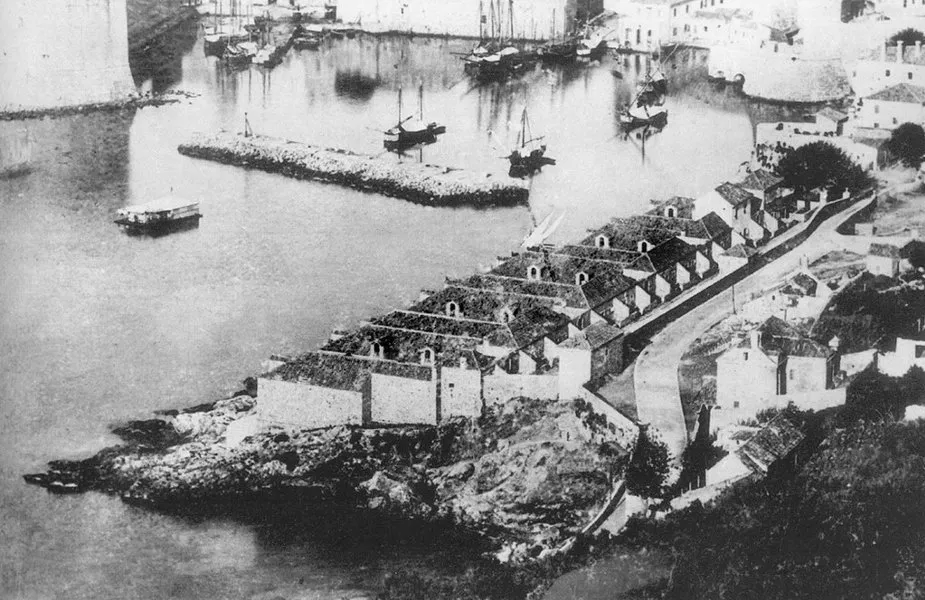

Construction of a large lazaretto in the immediate vicinity of the city walls began in 1590. Its location, today a neighborhood called Ploče, was significant. Medieval Ploče sat next to the city’s main harbor and inland road connecting Dubrovnik to eastern cities. Merchants, sailors, and travelers could therefore be sent directly into quarantine, without the need for time-consuming transport to islands or further inland.

The Ploče lazzaretto, from the Miroslav Krleža Institute of Lexicography

At this point, a standardized quarantine system was in place. Plagues continued to reap destruction across the Mediterranean but didn’t breach the city’s walls again for another century.

The success of Dubrovnik’s counter measures should be viewed in a broader context as well. The republic was wealthy, politically stable, and had a small population and territory. It was, therefore, at a relative advantage in the fight against plagues as opposed to bigger and less organized regions.

An unwanted return

The 17th-century Plague of the Maids in Dubrovnik (1691)

The last plague to break into the city of Dubrovnik was the so-called Plague of the Maids (Peste delle serve) in 1691. The plague’s name sprung from the belief that maids, because they suffered from it the most, caused it. Thought to be the most malnourished demographic group of the time, maids probably had the poorest immune systems and were therefore hit hardest – not because they actually started the plague.

Facing a system advanced for its time, how did this final plague infiltrate the walls? In the 17th century, Dubrovnik was flanked with enemies. The Venetian Republic and Habsburg Monarchy saw the city for what it was: a strategically located, highly prosperous port. War wasn’t actively waged, but an influx of guerilla robberies plundered the city, likely encouraged (or at least tolerated) by either of the two surrounding powers. Robbers would often arrive from plague-ridden areas and, presumably, were the disease’s real carriers.

From the archives of the University of Oregon

At first, the plague was handled as it had been in the past. Each new case was treated identically, be it servant or nobility. Movements and entire social networks were reconstructed to quarantine anyone presumed sick. Investigations were carried out promptly as lost time meant multiplying contacts and spread of disease.

A week after the first death, when the seriousness of the plague was realized, the government quarantined the entire city. No one was to leave their house – with the exception of the highest members of government, including the kacamorti. Punishments included fines, which were used to cover the Health Magistrate’s expenses: salaries, patient treatment and food, cleaning, burial expenses, and construction of quarantine centers. Quarantining was easier in villages, where individuals could be separated on their family estate in barns or makeshift hay abodes. Inside the city, though, possibilities were limited. Lazzaretti soon became overcrowded, so monasteries, palaces and family homes were also transformed into quarantine centers.

During the Plague of the Maids, kacamorti were given special permissions. They’d walk the streets several times a day calling out names of each resident. If a reply didn’t come, the house would be put in isolation and an investigation would be conducted. Kacamorti threatened citizens with drastic measures for breaking rules, including being shot with an arquebus (an ancient type of long gun). Only kacamorti could give permission for movement outside of the city, and they were also given the right to carry out severe punishments and burn property. Abuse of power was not unheard of. Records show, for example, a falsely accused individual proven innocent against the kacamorti in court. But not before the latter had already burned most of the former’s property.

At this stage, the government was aware of trade as an urgent need, without which hunger – and looting – would arise. So, designated camps were erected and precautionary measures defined on how to clean goods. Butter was melted, and meat, fruits, and vegetables were washed with water. Wood and metal were exposed to fire. Anything thought to be a disease transmitter (included wool and cotton) spent 45 to 60 days in a lazzaretto. There, it’d be aired out, smoked out and/or washed with vinegar.

Diplomacy and international communications related to the plague were upheld. All travelers were required to inform authorities on the status of the plague at their points of departure. The government sent health information to Kotor and Zadar and vice versa. The republic sought to put up a strong outward-facing front to keep its economic interests safe. If the city was seen as safe for trade with the strictest precautionary measures being taken, money would keep flowing into the city.

The Plague of the Maids was pronounced finished in mid-June of 1691. Three days of festivities followed the proclamation.

The 2020s

The last time a quarantine was pronounced within Dubrovnik’s walls was in the 17th century, until the first cases of COVID-19 were confirmed in the city in March 2020.

So, what can we learn today from the history of quarantines in the city that invented them?

© fjaka

The success of Dubrovnik in fighting the plague is clear. By the end of the 16th century, its honed quarantine system kept plagues (which continued to devastate the rest of the world and nearby regions) out of its walls for a century. The importance of recognizing a crisis situation and reacting to it quickly is a takeaway lesson for us today. Quarantining, including in self-isolation form, is currently believed to effectively stop the spread of disease. Minimizing social contact can make or break a society, its entire healthcare system and mean the difference between life and death.

Setting aside Dubrovnik’s poor healthcare system as a victim of its time, we can shine a light on examples of the dangers of power abuse. For all the good work many kacamorti carried out, there were cases of personal vendettas, or just pure cruelty. During times when some type of hierarchy is required to systematize, record and carry out necessary measures, those at its top shouldn’t forget what they were chosen to do. And that’s saving lives and helping suffering people, not causing further pain in already turbulent times.

Stigma is another way of adding flame to the fire and causing not only misinformation, but also misery. The Plague of the Maids, in its very name, places the blame of an entire disease on an innocent group of people. Also present in the past was the stigma associated with those healed from a disease. Though we aren’t likely to liken survivors to the supernatural anymore, we should remember the importance of patient confidentiality when it’s desired, the advice survivors can give us, and, most importantly, the strength of mutual support.

The former Ploče lazzaretti are today home to an art workshop, a charity organization, and a multimedia museum. They also serve as a venue for concerts and events. This month, Zagreb’s Arena Center and Split’s Paladium were made into hospitals and quarantine centers, becoming, in a way, modern versions of lazzaretti.

This seeming topsy-turviness should actually remind us of our ability to work together to transform and adapt as circumstances require. This is, after all, what makes us human.

As we brace for the future, let’s reflect on the past.

Any opinions expressed in this piece are solely those of the writer and not necessarily shared by Time Out Croatia