Recently screened at the prestigious DOK Leipzig documentary film festival, El Shatt – A Blueprint for Utopia tells the story of the 28,000 displaced Dalmatians who set up camp for two years in the Egyptian desert during World War II.

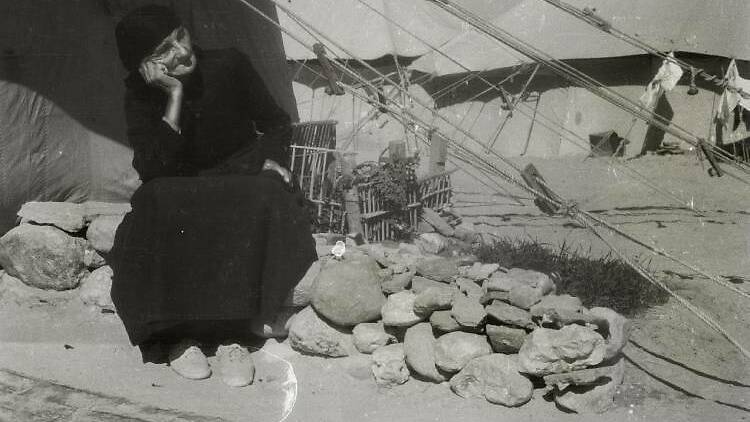

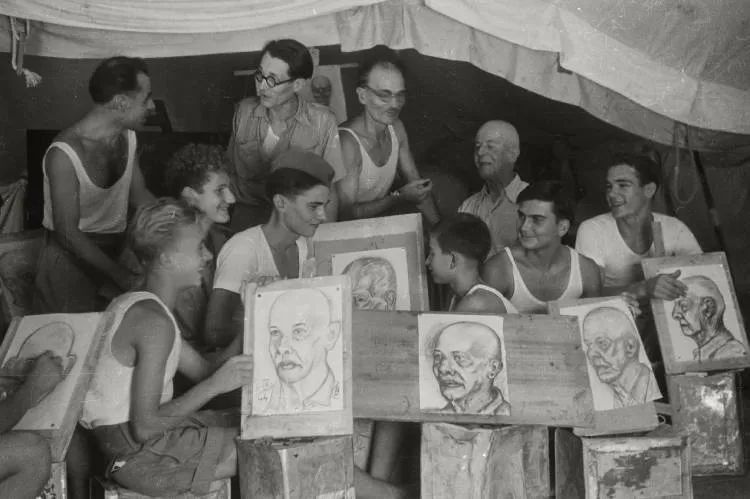

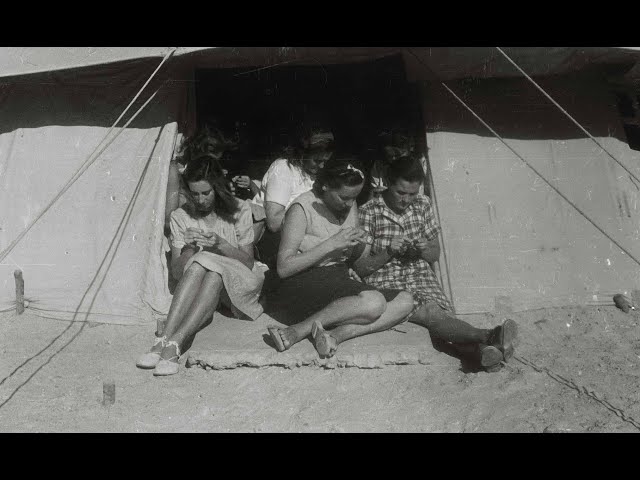

Evacuated by Partisan leader Tito, women, children and men unable to fight were shipped to a refugee centre by the Suez Canal, overseen by the Allies. There, on the sands of El Shatt, they created a model Communist society, in preparation for their return to their homeland once Tito took control.

Croatian filmmaker Ivan Ramljak explains what attracted him to this extraordinary story, reveals his own personal connection and unpicks the threads of a complex documentary that took him five years to make.

“My grandfather was one of the Dalmatian doctors who went with the first wave of refugees,” begins Ramljak, 49, now with a dozen documentaries and features under his belt.

“He died when I was very young. His story was told among my family, so I knew about it and always found it interesting. Then seven years ago, my grandfather's brother died. In his house, his family found my grandfather’s diary. It’s very brief, maybe 30, 40 sentences, a line every day or so. It starts with the day that he found out he was leaving.”

“The first entry reads: 'I need to go to El Shatt. My wife will be worried'. So, that was some kind of starting point. The idea was to try to tell the story about my grandfather, a personal family history.”

“At some point I realised that it should be about people who were there, who were still alive and who could tell their own story. Everything is related through their testimonies. There are no views from historians. These are personal stories told from first-hand experience.”

“The visual part is made from archival photographs and the little bit of film that exists. There is a British 17-minute long documentary called The Star in the Sand, made back in 1944, and that’s more or less the only film material.”

“We shot some scenes in the place where the camp used to be, because there’s a cemetery there, and we filmed three fictional scenes.”

“The subject is not very present in today’s Croatia. It’s one of these positive stories about Socialism that is generally avoided. There’s not a lot of talk in public about El Shatt. There was an exhibition at the Croatian History Museum in Zagreb in 2007.”

“As soon as I spread the word about what I was looking for, people from different locations got in touch with phone numbers and addresses. It was actually quite easy. When you’re working on a subject like this, that a lot of people are emotionally connected to, they think that it’s very important to tell their story. And they’re very willing to help with anything you need.”

“I particularly needed people who would have been at least eight or ten years old while they were there. They would have a more complex memory as to what was going on.”

“The problem was that I was doing the film in the middle of the pandemic. So, it was not a problem to find them, it was more a problem to interview them. I had to enter the homes of old people. That was a challenge. I had my own system of preservation. I would stay home for five days, not seeing anybody before I left. Nobody could fall ill because of any pandemic problems. In the end, I interviewed around 30 people. Eight of them are in the film.”

“The whole process lasted five years. I have never worked on a film for that long. When you have such a complex task, and you’re doing it for such a long time, at some point you lose the ability to be aware of what you’re doing. What kind of film will this be?”

“We’ve had around 6,500 people watching it in cinemas. Which, for a documentary in Croatia, is very successful. Last week we had our international premiere in Leipzig, one of the most important documentary festivals in Europe. So, we’ve had recognition from audiences and from the industry, which is nice and quite rare, actually. I’m extremely happy. It’s above my expectations.”

“It was in Sarajevo this month, then in November, there will be screenings in Belgrade and also in Den Haag. I expect the film will be shown over the next year at different festivals, presumably including all the former Yugoslav countries.”

“I hope that Croatian television will also screen it. We’ll have to see if they’re interested, They should be, I think.”

“I’m very pleased with the result. I’ve been making films for the last 16 years and a few documentaries weren't so easy to do, but this one was very complex. We had to mix lots of different things. We had archival photos, we had archival film, we have the documentary scenes that we shot now, we have these fictional scenes… to make everything gel, that looks complete, that was a big challenge.”

“And especially because the whole story is very episodic. In the beginning, our idea was to present this story as one about a collective, to tell it like some kind of collective memory. So, you don’t have one person with his storyline, you have lots of people and lots of little subjects that you somehow need to put in the right order and connect in the right way. They need to form something that's whole.”

El Shatt – A Blueprint for Utopia, 96 minutes with English subtitles.