Somehow concrete has never seemed so popular. It’s impossible to surf your smartphone or open a travel magazine without being bombarded with pictures of angular grey buildings shot under a moody glowering sky, together with a catch-line suggesting that it’s about time these misunderstood monoliths were accorded the love they deserve. Brutalism has become a buzz-word, applied somewhat over-enthusiastically to the buildings of Central and Eastern Europe as if any tourist’s encounter with this region is bound to involve a significant degree of masochistic, abrasive pleasure.

It’s a subject thrown into sharp relief by Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948-1980 at New York’s MOMA, a major exhibition that runs until January 13 2019. Covering housing estates, public buildings, hotels and war memorials all over the Yugoslav federation (and particularly in Croatia), it sets the architecture of the period in its social and political context, and provides a welcome corrective to the isn’t-it-bizarre approach of all those pictorial blogs and social media posts.

It’s as an exercise in setting the historical record straight that the current enthusiasm for modernism is most valuable. The architects and designers at work in Croatia during the first four post-war decades really did produce unique buildings and monuments in large quantities, and it’s about time that the encyclopedias were rewritten to give them their rightful place.

European cultural history always was a bit distorted, both by a lack of knowledge about Central and Eastern Europe; and by a discernible sense of post-1989 western triumphalism, in which it was assumed that “the East” wasn’t just a failure in the political sense, but also in terms of innovation, lifestyle and popular culture.

In Croatia at least, it is not so much the brutalism that was beautiful as the level of social planning that went with it. Housing estates like Split-3 in Split, or the individual blocks of Novi Zagreb, were built with shops, kindergartens, health centres and open spaces included in the general plan. It’s the way in which these modernist developments were an expression of social priorities that finds such a positive echo today.

Unlike the stately housing blocks of Split-3, the modernist hotels of Croatia’s Adriatic coast were never intended for local citizens to actually sleep in. Their main purpose was to attract the hard currency of Western tourists, and they were mostly built in the kind of cool, Mediterranean style that would look good in a travel brochure. Many of these hotels ended up as classics of leisure architecture – one thinks in particular of the stepped terraces and hanging gardens of Dubrovnik’s Libertas or President hotels.

However, the epoch also produced its eyesores: Boris Magaš’s Haludovo Hotel on Krk is typical of the grey lumps that have become an obsession for fans of the brutal. However one can’t avoid the suspicion that it owes much of its aura to the fact that it is currently derelict. Ruins make us sentimental, prone to overvaluing buildings that were never that good in the first place.

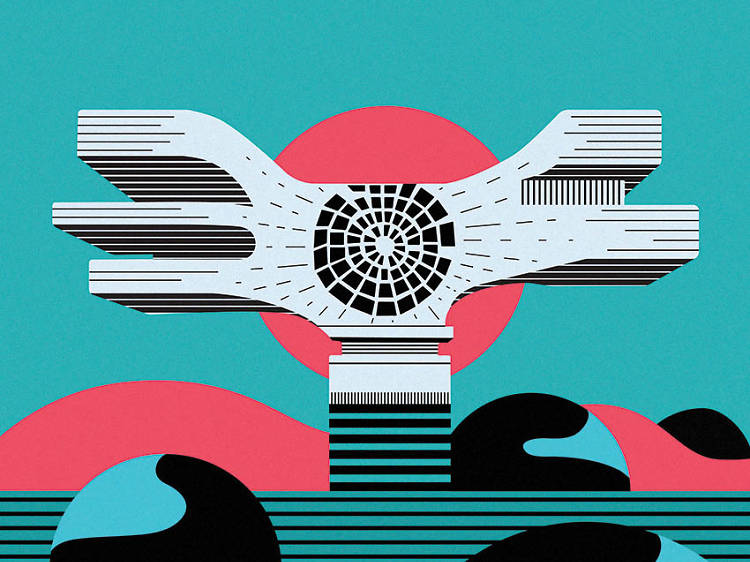

It’s an argument that might be extended to the memorials built to commemorate the antifascist partisans of World War II, photographs of which are hurtling across the Internet like misshapen asteroids. Some of them are outstandingly ugly. Indeed one of the services performed by exhibitions like the MOMA show is that the bad monuments are filtered out, leaving us to contemplate the masterpieces – Bogdan Bogdanović’s Stone Flower at Jasenovac in Croatia, for example, Dušan Džamonija’s winged fireball at Podgarić in Croatia, or the breathtaking Valley of the Heroes ensemble by Miodrag Živković and Ranko Radović in Tjentište in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

© Imelda Ramović | Spomen Spomenicima

The tendency of some writers and bloggers to present these monuments as bizarre and otherworldly has been criticized by many in Croatia, who argue that their status as wacky visual click-bait has shorn them of their social and political context. However most of these monuments were built deliberately as outlandish spectacles that would shock the viewer – otherwise, they wouldn’t have used all that angular concrete.

Western representations of these war memorials (the MOMA exhibition included) rely heavily on gritty photographs set against cloudy skies as if to reinforce our preconceptions of former-communist Europe as something grey and overcast. Providing a startling contrast are local artist Imelda Ramović’s ravishingly beautiful graphics of partisan monuments, published in her 2017 book U Spomen Spomenicima (“In Memory of the Memorials”). These warm and heartening images rescue the monuments from the ruin fetishists and make them look radical, relevant and full of promise.

© Duška Boban | Motel Trogir

© Duška Boban | Motel Trogir

Indeed there are signs that Croatia is becoming increasingly proud of its modernist riches. The Split-3 housing estate is the subject of increasingly vocal affection among locals, a city-defining landmark that is almost important as Diocletian’s Palace. The same city’s swoon-inducing Poljud Stadium, designed by Boris Magaš in 1979, is a globally-celebrated sporting classic. Ivan Vitić’s playfully Mondrianesque residential building on Laginjina ulica in Zagreb is an unashamed slab of primary colour that is anything but brutalist.

There is a huge number of derelict masterpieces too. Neither the mini-monoliths of Vitić’s Motel Trogir or the breathtaking circular sweep of Rikard Marasović’s Krvavica children’s resort survived the fall of communism or the subsequent period of “transition”, a period which started over a quarter of a century ago never seems to end. Given the social and economic ambiguities of our present age, it’s no surprise that these concrete semi-ruins now loom large in our imagination as symbols of lost promise, of a future carelessly mislaid.

'Our fascination with Sixties and Seventies modernism is an indirect critique of our current regression to a kind of pre-modernity' says novelist, newspaper columnist and proud Split resident Jurica Pavičić. 'People see bad urbanism, bad neighbourhoods, politicians who favour private investors instead of public interest. They see kitsch monuments and a lowering of standards in visual taste, and they project their problems onto an imaginary, better past which was obviously not that perfect as they picture it, but certainly had different priorities.'