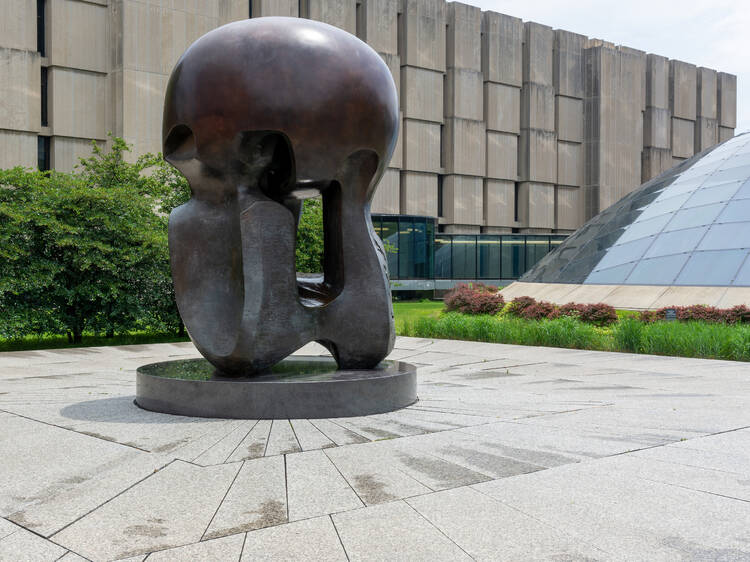

The Museum of Science and Industry

The fabled White City sprung up in Jackson Park during the World's Colombian Exposition of 1893, hosting technological and cultural exhibitions for six months—but the majority of the noeclassical buildings were temporary and designed to be torn down at the event's conclusion. One exception was the Palace of Fine Arts, built with bricks to protect the art displayed there during the Exposition. Eventually, the vacant building was transformed into the Museum of Science and Industry, which opened in 1933. Builders replicated the Beaux Arts design with Indiana limestone, retaining the columns and ornamentation of the original structure. Stand on the museum's southern steps, look across the Columbia Basin and imagine the White City stretching out in front of you.