[title]

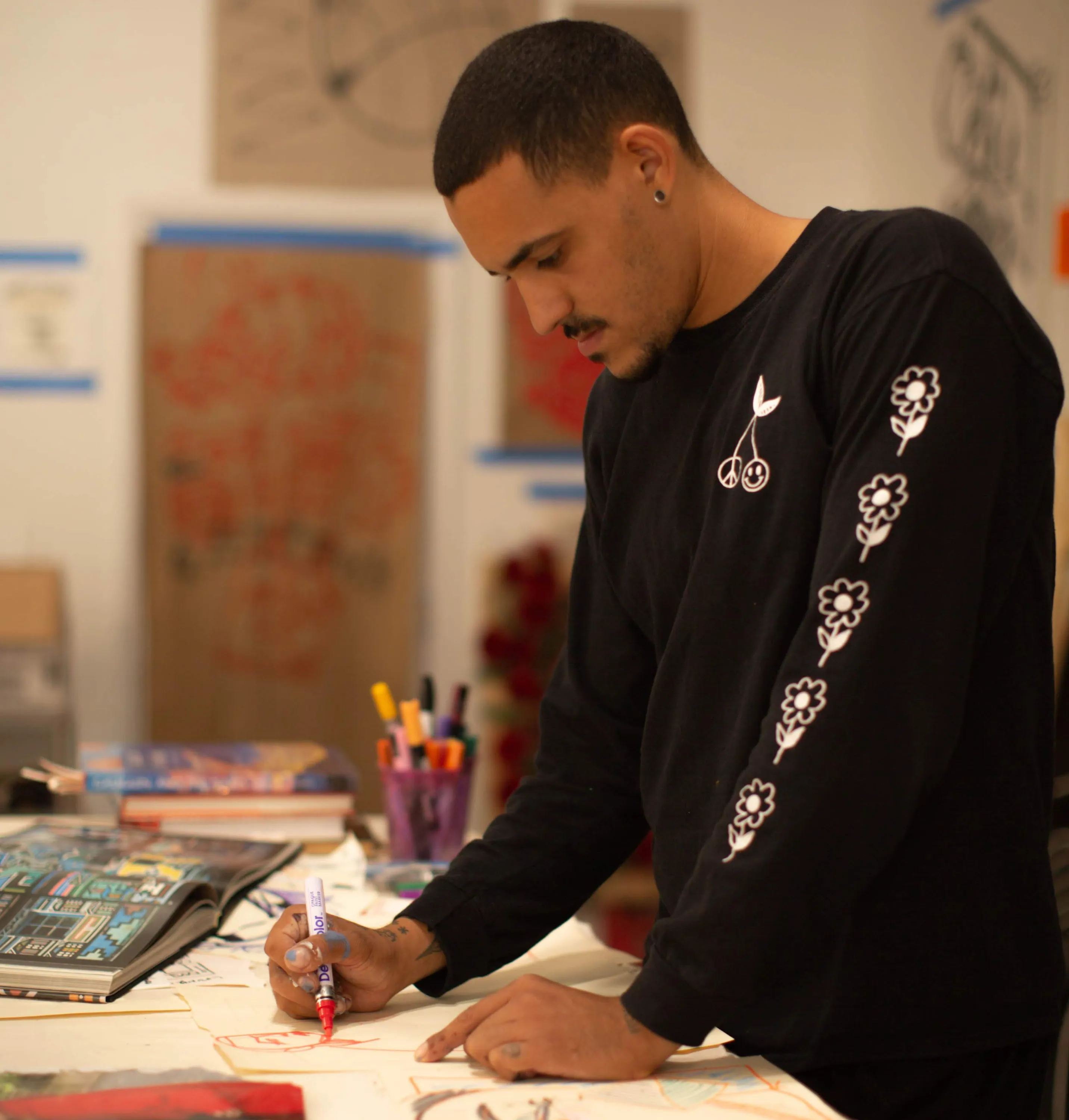

Last fall, the Chicago Bulls unveiled a mural dedicated to the Black Lives Matter movement prominently displayed on the side of the Advocate Center, the team's practice facility on Madison Street. Depicting a group of young Black people (one in a ’96 Bulls NBA Championship shirt) holding a sign and raising their fists, the stylized painting was just one of many public works that New Orleans-based artist Langston Allston completed during a long stint in Chicago last summer, putting his wide-eyed figures on everything from boarded-up windows to the side of the old Polish Triangle newsstand.

Allston has always felt a connection to Chicago, growing up a few hours south in Champaign—a city where there wasn't much of a graffiti scene to guide him when he was first getting started. “I just started painting and people saw it, liked it and didn’t think of it as vandalism,” Langston says, explaining how he got gigs painting the sides of garages and alleys as a young artist.

During the few years he spent enrolled in the painting program at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Allston would frequently travel to Chicago to visit friends and family, soaking in the more vibrant landscape of graffiti and other public art that the city hosts. After a few years of college, Allston decided to drop out ("I did not really enjoy going to actual school," he says) and travel the country for a few years as he continued to hone his craft and create art. His formative experiences in Chicago have brought Allston back to the city nearly every summer, where he's become involved in an art scene that continues to inspire him.

Over the past few years, Allston has hosted shows in local galleries and created a gigantic painting on the Logan Square permission wall (near Fullerton and Milwaukee Avenues), but his preference over the past year has been large-scale works that allow him to integrate his imagery with architecture. For Allston, painting a mural is both a mental and physical challenge, as he plans an image that makes sense for its real-world canvas and then maneuvers his body and tools to get the paint where it needs to be. “I love working on a large scale because I like to use my whole body when I paint,” Allston says, “It’s the thing that keeps me most focused and most engaged while I’m working.”

Last summer, Allston painted so many murals in Chicago that he lost count, taking advantage of the public canvases that were created when businesses across the city boarded up their windows in response to protests against the police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor. Paintings on boarded-up shops (such as the Exclusive streetwear store in Auburn Gresham) gave way to commissions from businesses like Dark Matter Coffee, Avondale Bowl and the Chicago Bulls.

I just started painting and people saw it, liked it and didn’t think of it as vandalism.

Allston is grateful for all the work he's been able to do over the past year, but he's also cognizant of the reasons why it was an especially busy year for him. Before 2020, Allston says that he had never received an offer to create artwork for a corporation, but as the Black Lives Matter movement became more visible over the summer, he and many other BIPOC artists started receiving design commissions from companies with deep pockets.

“It’s a little bit of a head-scratcher, because you’re like ‘What is making you excited about this work now?’,” Allston says. “Is that coming from a genuine place of reflection or is it ‘Oh, this is a popular thing that we have to tap into in order to improve our brand’?”

The murals and paintings that Allston created in Chicago over the summer were largely based around themes of love and empathy, emotions he felt were in short supply during an especially bleak time, and from his perspective, “felt like a radical gesture in that exact moment.” But looking back on the art he created over the past year, Allston is candid about his uncertainty that he was able to address the nation's continued racial inequality in a way that accentuates the severity of the situation.

“I do have a concern that sometimes my work is a participant in this—that even some of the displays of unity are, to a certain extent, erasure of the fact that we were pushed to the point of nationwide violence,” Allston says. “We were demanding immediate systemic change and we still didn’t get it.”

I’m ready to switch tack and make something different.

These feelings could manifest themselves in a new mural that Allston is returning to Chicago to paint in March, or via a show he's planning to present in the city when the weather warms up. Before he travels to Chicago this summer, he'll be completing the first residency of his career at the Joan Mitchell Center in New Orleans, where he's hoping to develop a new body of work that he'll eventually display. When Allston speaks about what he might produce, he seems unsure of what he wants to create but confident that it will mark a turning point.

“I’ve been spending so much time making, not the same work, but work that I think sings the same note,” Allston says. “I’m ready to switch tack and make something different.”

Most popular on Time Out

- Take a look inside Chicago’s ‘Immersive Van Gogh’ exhibition

- The best things to do in Chicago this weekend

- Believe it or not, Chicago is expected to get even more snow in the coming days

- 65 Chicago restaurants and bars that permanently closed

- The 39 best things to do in Chicago right now