The Museum of Science and Industry is a place devoted to understanding the world around you, whether you're exploring the forces of nature in "Science Storms" or walking around the massive German U-505 submarine. But when we're not caught up in the interactive exhibitions that fill this massive Hyde Park institution, we sometimes find ourselves thinking about the stories behind some of the museum's most famous displays and the historic building that houses them.

To uncover some secrets of the Museum of Science and Industry, we consulted with Dr. Voula Saridakis, who works as curator and describes herself as the "voice of the artifacts" that populate MSI's extensive collection. Thanks so years spent working in the building, she's also learned about MSI's history and was able to reveal some little-known facts about exhibits, the museum's origins and seldom-seen objects that are stored in its collection.

How the vortex in "Science Storms" works

Ever since it opened as a permanent exhibition in 2010, the 40-foot vortex in the "Science Storms" exhibition has become one of the museum's most iconic displays. But how did the museum manage to create a gigantic spinning column of visible air? According to Dr. Saridakis, it's accomplished by using two fans the size of Volkswagen Bugs that create the rotational airflow, with one positioned above and another below. "The visible part that people see is a fine water mist that’s created by 48 ultrasonic foggers that sit in a small pool of water under the floor grate," Dr. Saridakis says. A series of levers allow visitors to manipulate dampers that control the shape of the air column—and you can also walk through the vortex (don't worry, you won't be blown away).

The story behind the Art Deco decor in MSI's north entrance

The building that houses MSI was originally the Palace of Fine Art during the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. "Unlike all the other fair buildings that were made with temporary materials and plaster, the Palace of Fine Art was made with durable brick substructure, because the artists and sculptors did not want to risk damage to their art in case of a fire or other disaster," Dr. Saridakis says. When the building was repurposed as MSI in 1933, architects built a structure around the foundation of the original building, using limestone from Indiana to create an exterior that echoed its Beaux Arts design. MSI's north entrance was originally the museum's main entrance, outfitted with Art Deco elements that reference the institution's connection to science, technology and industry. That includes towering bronze doors outfitted with panels that represent scientific disciplines as well as interior plaques that depict Greek gods associated with science. While the portico no longer serves as the museum's entrance, you can peek through the glass doors on the main level and take in the vintage decor.

A rare radioactive toy in the museum's collection

With more than 35,000 items in it collection, MSI has a wide variety of rare artifacts—most of which aren't on display to the public. One of the most interesting pieces the museum has acquired is an Atomic Energy Lab manufactured by A.C. Gilbert—the same company that introduced Erector sets. Also known as "the world's most dangerous toy," the company produced about 5,000 units of the Atomic Energy Lab between 1950 and 1951, selling them for $50 (which is the equivalent of more than $500 today). The lab is stocked with equipment, including a cloud chamber that allows you to see alpha particle decay and a battery-powered Geiger counter. It also includes a selection of low-level radioactive sources and uranium-bearing ore samples, housed in jars and plastic disks. "There is a lab that did some experiments to find the level radiations coming from these samples," Dr. Saridakis says. "It's the equivalent to one day of UV radiation from the sun, providing that the samples are not opened."

How a Boeing 727 was moved into the museum

A Boeing 727 airplane suspended from MSI's third-floor balcony acts as the centerpiece of the museums recently-revamped "Take Flight" exhibit, allowing visitors to step inside the vintage airplane and observe some of its inner workings. Before it came to Chicago, the plane flew commercial flights for United Airlines between 1961 and 1991, carrying around 3 million passengers to their destinations. The decommissioned plane landed at Meigs Field in 1992 and was put on a barge to Indiana, where it was stored until it was floated back to a beach near MSI in 1993. Much like the U-505 submarine 40 years earlier, the plane has to be moved across Lakeshore Drive, but that wasn't the most difficult part of the 727's journey. "In order to get it into the museum they had to remove the wings and the tail as well as one of the 32-ton ionic columns on the west entrance," Dr. Saridakis says. Once the plane was in the building, it was reassembled and mounted in its currently position.

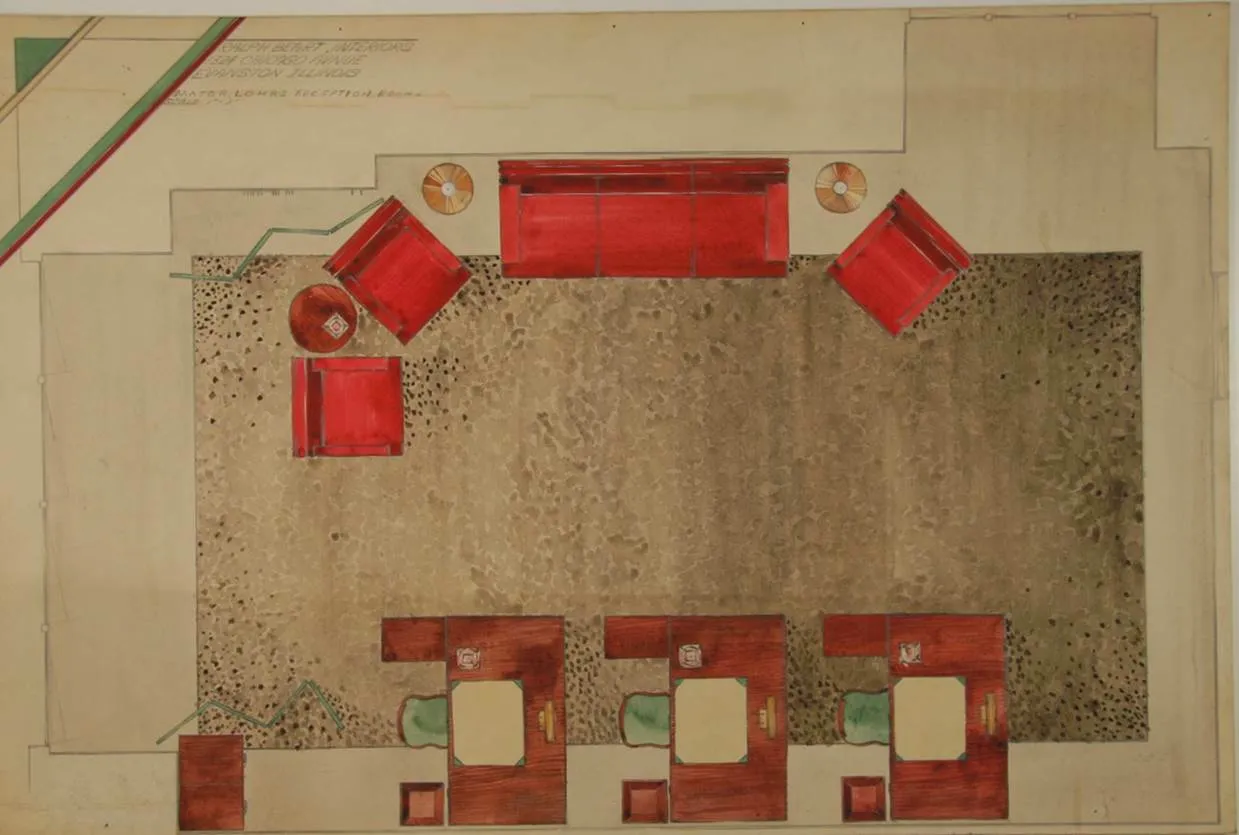

The secret location of a former MSI president's office

As president of MSI from 1940 to 1968, Lenox R. Lohr oversaw the launch of several cutting-edge exhibits that came to define the museum, including the U-505 submarine and the annual "Christmas Around the World" display. He worked out of an office located just inside the entrance of what is now the "Extreme Ice" exhibit, in a space that has been converted to a boardroom that is used by museum staff for private events and meetings. The space that the boardroom occupies functioned as Lohr's outer office, which Dr. Saridakis says is "demonstrated in [a] bird's eye rendering of the space, where you see several chairs for guests as well as three desks for the secretaries, along with three chairs and three ashtrays—because it was the 1960s after all." A door in the corner of the boardroom leads to a section of what used to be his inner-office—the other part of Lohr's former workspace now houses the Silver Elevator bank which takes guest from floor to floor of the museum.