It’s hard to imagine now, but when Boka restaurant opened nine years ago, co-owner Kevin Boehm had to beg for media coverage. “The only thing that was written about us before we opened was, like, three lines in Dish [Chicago magazine’s weekly e-newsletter],” Boehm, who’s also a partner in Girl & the Goat, GT Fish & Oyster and Balena, says. “And that was just about our cell-phone booth.”

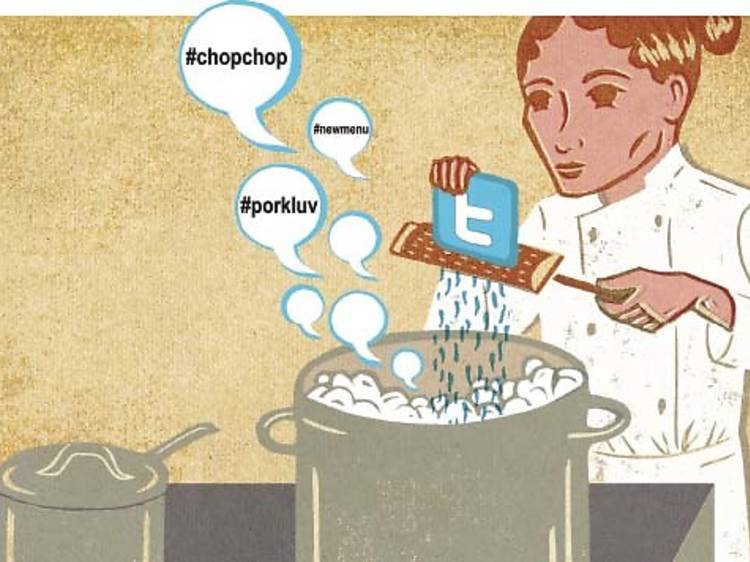

These days, between Twitter, Facebook and any number of food-centric blogs, it’s hard not to know every intimate detail about a new restaurant months—sometimes years—before it even serves its first customer.

I admit I can get caught up in all the pre-opening hype, too, beyond the fact that as a food writer for the last 12 years, it’s my job to stay current. Whether it’s the mysterious trailer for Next’s current Sicily menu, a video from soon-to-open Belly Q on the making of its handcrafted leather aprons or any number of behind-the-scenes construction photos, I—and in the case of Next, tens of thousands of others—can’t get enough. But I also can’t help but reminisce about the days when restaurants just, well, opened, and I wondered if chefs and restaurant owners do, too.

It’s fitting that when I speak with Bill Kim and Yvonne Cadiz-Kim, they’re on their way to a three-day photo shoot for Belly Q, the Randolph Street restaurant they’re opening with Cornerstone Restaurant Group and Michael Jordan in the one sixtyblue space. While the restaurant isn’t slated to open for several weeks, the couple, who also own Urbanbelly and Belly Shack, want to be sure that from day one the website will have plenty of food porn for their future customers to look at.

“You can’t let time pass. We don’t have that luxury anymore,” says Kim, adding that the first thing they did after they established the domain name was create Facebook and Twitter accounts for the restaurant. “The challenge now is how to stay ahead of the creative curve knowing that it will change instantaneously,” Cadiz-Kim says. While they both admit the speed at which social media operates “keeps us up at night,” they’ve accepted that it’s part of running a successful restaurant these days. “We are adapting,” Kim says. “I respect all the chefs I’ve worked for but some didn’t get the chance to re-create themselves and it’s sad. I’d rather just retire.”

When Matthias Merges was executive chef at Charlie Trotter’s, social media was never part of the equation. But he knew that wouldn’t be the case at his first restaurant, Yusho. Prior to opening the Avondale spot last December, Merges posted photos of the restaurant being built and, later, images of dishes and cocktails. And he continues to do so, because he reckons that 10 to 15 percent of his restaurant’s reservations can be attributed to things he posts. “If you’re not cutting fish or looking over accounting, then you have to be on social media,” Merges says. “If you miss that opportunity, it’s done.”

It is possible to be overzealous. In October 2011, brothers Michael and Patrick Sheerin, the chef-owners of Trenchermen, which just opened, released a video trailer and said the restaurant would debut in early 2012. They then fielded questions about their progress for the next nine months. “We were the most anticipated restaurant to open last winter, then spring and now summer,” Michael says. “Because there is so much exposure online, people want things to happen faster,” says Patrick.

“It’s a double-edged sword,” Boehm says. “You want to get out there and scream, Hey, we’re open! But at the same time, you don’t want to do 370 covers on the first night.”

That may be why not every chef is a Twitter and Facebook fiend. Over at Goosefoot, chef/owner Chris Nugent posts only once a week. It’s not that he doesn’t understand the importance of social media—he loves the number of inquiries he gets when guests, like wine guru Alpana Singh, tweet while dining there. But his 34-seat restaurant is booked months in advance, so the only thing social media leads diners to is a long wait list. “We’re focusing our energy right now on returning guests’ phone calls and getting back to their e-mails instead of creating more voice mails and e-mails,” Nugent says.

While Acadia chef/owner Ryan McCaskey did a pre-opening blog, he finds that he has to force himself to do much social media now that his South Loop restaurant is open. “I’m old school,” says McCaskey, who’s been in the business for 28 years—and who hasn’t had a cell phone since 1999. “I’d rather just put my head down and work and provide a great experience for my customers,” he says. “I don’t mind being in a bit of a bubble.”

Then there are the Phillip Fosses of social media: People who perhaps liked it too much. “I’ve learned to keep my mouth shut,” says Foss, the chef-owner of EL Ideas, whose putting-it-all-out-there tweets (including ones that compared cooking mussels to sex and made reference to bongs) got him into hot water with his former employer Lockwood. “I’m a lot more diplomatic.… I still try to be as honest as I can but without ostracizing anybody.”

Boehm agrees. “You have to be really careful. If you say or do the wrong thing at this point, there are so many eyes on you that people will pounce on it,” he says.

Which is why these days, many restaurants are leaving social media to the pros. Wagstaff Worldwide, an old-school PR firm, now takes care of 15–20 Twitter accounts for Chicago restaurants; meanwhile, over at newer firm Jamco, social media is the focus. So that chef you follow on Twitter who’s writing about his new shrimp burger? Probably not actually him. But one upside of a pro doing the tweeting is that, unlike everybody else on Twitter, he or she has rules. Like this one from Wagstaff’s Emilie Zanger: “If you don’t have something interesting to say, don’t post.”