I’d like to put forth, in this article, the argument that this is Haymarket Books’ time. Despite consistently publishing provocative books from the left end of the political spectrum, the tiny Chicago press doesn’t have the largest profile in the local literary or publishing scene. That, though, speaks more to the left’s marginalization in American culture than it does the quality of the work coming out of the untidy Ravenswood offices.

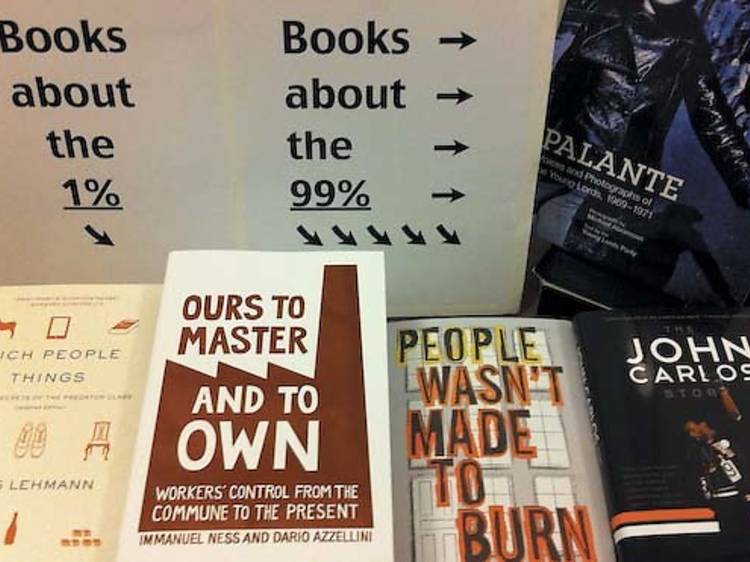

But that is now, obviously, changing. The Occupy protests have brought left-of-liberal concerns to the fore, changing the national conversation. And anyone interested in catching up on that conversation might want to stock up on the backlist of Haymarket, which for the past ten years has been building a lending library for just such a movement. In fact, Haymarket has set up shop in several of the towns where the movements have taken off.

“There’s kind of an appreciation for books and ideas in the movement that’s very encouraging to us,” says Anthony Arnove, one of Haymarket’s founding editors. “We’ve been going down to Occupy Wall Street and tabling, and selling a lot of books.”

It would have been difficult to see this success in the press’s early days. Arnove and managing director Julie Fain had worked together on the International Socialist Review and had begun to feel the itch to make the transition to book publishing. At first, they put out a couple of books without any distribution or real structure, selling them at events and with like-minded merchants. The first book was The Struggle for Palestine, a collection with contributions from heavyweights like Edward Said. And once momentum began building around that book, they decided they needed a name.

“The political legacy of the Haymarket martyrs, and the connection to Chicago history and politics, was perfect,” Arnove says. “There are books and movements from history that we can learn a lot from today.”

But the first big success story for Haymarket came in 2005. Little-known sports writer Dave Zirin got a call from Arnove, who had read columns Zirin was writing for Prince George’s Post, a small paper in Maryland with, as Zirin puts it, “a circulation that could fit into a small room.” Arnove was looking to do a sports book, and the two put together a collection of Zirin’s work investigating the intersection of sports and politics. That book became What’s My Name, Fool? and was instantly a huge success.

“I remember he went on Democracy Now! with Amy Goodman,” Fain says. “And after that, I looked at the sales numbers and said, ‘What is happening?’ ”

“Without Haymarket, I have no career,” says Zirin, who has now written for major newspapers and magazines, appeared on numerous news programs and notched several books since. “They see books as books, not books as units. And for a writer, that’s such a rarity in this business, it’s like finding gold.”

Zirin is out on tour with his new book, The John Carlos Story (Haymarket, $22.95), touring with the famed Olympian who raised a Black Power salute from the bronze medal podium at the 1968 Olympics. The two are on one of the most unusual book tours going, planning speaking events around visits and teach-ins at various Occupy protests.

And that is maybe what makes Haymarket the most exciting and relevant press right now: the sheer immediacy of its work. In the midst of a housing crisis, it published Joe Allen’s People Wasn’t Made to Burn. A couple of weeks before the global population ticked up to seven billion, it published Too Many People? And, says, Fain, the press is coming out with a short run of pamphlets, introducing some of its books and the ideas in those books to the protesters camped out across the country.

“We always knew there would be a time when—given how difficult things were getting—the ideas we were keeping alive would become extremely relevant in a very short period of time,” Fain says. “So over those ten years, we consistently published books that held to the idea that there is a chance for a better world. For all of us, this is just an amazing moment. It is what we’ve been publishing for.”