“One thing I’ve noticed time and again in the prison system is how quickly people in the outside world forget you,” writes Damien Echols in his haunting new memoir, Life After Death (Blue Rider Press, $26.95). During his 18 and a half years on death row, Echols often felt invisible. Other times, he had company in the form of thousands of letters, many written by total strangers: “People going through divorces, people losing their children…they all write and tell me their personal business.”

Since 1994, Echols’s own business has been widely public. That year he, Jason Baldwin and Jessie Misskelley, then teenagers, were falsely convicted of murdering three boys in West Memphis, Arkansas. They became the subject of numerous news stories, books and documentaries, including HBO’s Paradise Lost trilogy, which brought considerable attention to their plight.

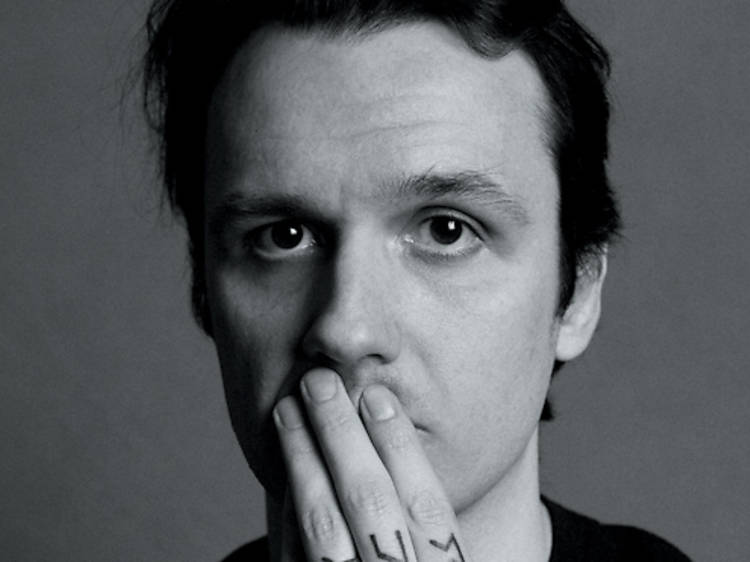

Strangers who wrote to the incarcerated Echols often treated him as a confidant or an oracle. “I think a lot of time when we write letters it’s almost like we’re writing to ourselves,” says the 37-year-old with a warm Delta drawl. Finally freed from supermax prison in August 2011, though not yet exonerated, Echols now lives with his wife, Lorri Davis, in Salem, Massachusetts. The unfinished saga of the West Memphis Three still resonates. “People come up to me and start crying, telling me [about] family members who were in prison for something they either did or didn’t do,” he says.

Life After Death—85 percent of which he wrote in prison; the other 15 percent after—preserves history in Echols’s own words. It also allows him some control over the conversation. He says many people want to tell stories about the case who weren’t closely involved but were “on the outer ring somewhere.” For instance, the forthcoming film Devil’s Knot (starring Colin Firth and Reese Witherspoon) makes a glaring omission. “Lorri did more work than the attorneys and private investigators put together,” Echols says. “I mean, we’re talking the key player in this case, and she’s not even in the movie!”

Echols’s memoir has been well-received and rightfully so. He renders the hardships of growing up poor in the South in stark detail—e.g., the miserable sharecropper’s shanty that, when his family moved in, was cluttered with junk: “Trash, sticks, broken tractor parts—it was all one big ocean of garbage, and the rats swam through it, delighted with their lot in life.” He bounces around in time, from death row to trailer park to mental institution, sometimes losing himself in fond remembrances of fall and winter. “It’s a prison writing style,” Echols says. There, you always keep your thoughts moving.

Now in the midst of a book tour, moving into a new house and getting the occasional matching tattoo with friend and supporter Johnny Depp, Echols has been going nonstop. The documentary West of Memphis, which he co-produced with Davis, Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh, is scheduled for a December 25 release. When he can finally slow down, he wants to open a meditation center.

Echols still writes. A recent tweet: “It’s cold outside! Not just cool, but outright cold! And there’s a bright orange pumpkin sitting on my porch. Life is pretty good.”

Life After Death is available now.