We’re consistently impressed by how broadly Loyola University Museum of Art (LUMA) interprets its mandate to exhibit “art illuminating the spirit.” Though LUMA’s affiliated with a Jesuit school, it’s embraced nonreligious art, showing Andy Warhol’s Silver Clouds in 2008 and an excellent retrospective of László Moholy-Nagy this spring.

“New Icon” continues this inclusiveness. Curated by Britton Bertran, whose Chicago gallery 40000 was a favorite before it closed in 2008, the show brings together nine local artists whose “icons” remain open to interpretation. Most of these artists, who include Pamela Fraser, Dan Gunn and Zachary Buchner, are up-and-coming if not established. We’re glad the Contemporary Arts Council, which promotes Chicago artists, provided the support for LUMA to showcase them. But, much as we like their work, we’re disappointed by how little of it achieves truly iconic status.

Sze Lin Pang frustrates the reverence we want to feel for one particular icon in her video installation the Place where there is no center and hence no Longing (2010). Visitors see footage of Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech playing on a loop. But when they put on the accompanying headphones, they hear a soft voice reciting something incomprehensible in a language Pang invented. The disconnect is jarring; stripped of King’s powerful words and voice, the grainy footage no longer moves us. While religious icons are meant to transcend linguistic boundaries, our awe of contemporary iconic individuals depends more on language and culture.

Kevin Wolff’s takes on the person-as-icon evoke a more visceral reaction. Two of the artist’s repulsive but incredible paintings spell out BOB in glistening peach-pink letters, thick and seemingly three-dimensional, as though Bob’s name is written in his own intestines. Wolff develops his work in part through molded-clay studies, as in his painting Bodybuilder (2008). While shirtless and well-muscled, its subject is also grotesque, with skin the color of Silly Putty and a melting face.

The unsettling way in which Wolff’s paintings evoke his sculpture reminds us that materials have their own language. Diana Guerrero-Maciá’s Devoured by Symbols (2008) and another hand-sewn fabric wall hanging convey a warmth at odds with their cerebral focus on semiotics. There’s gold leaf galore in LUMA’s Martin D’Arcy Collection of medieval, Renaissance and Baroque art, which Bertran cites as an inspiration in the broadside that serves as the “New Icon” catalog. In 2010, we get imitation gold leaf, and the small abstract sculptures by Buchner that it adorns recall mutant gold ingots rather than the glory of the divine. The pink and purple glitter that William J. O’Brien sprinkles over Corpse, an anthropomorphic figure made out of fabric, yarn and sticks, transforms what would otherwise be creepy into a strangely comforting, cheery piece.

Color and light, which make stained-glass windows so effective, also mesmerize in a few of Gunn’s installations. The electric-blue paint that covers a Lycra panel in Object of Interaction (2009) has an unearthly glow, as other small, mixed-media works come off as fetish objects. Fraser’s ethereal paintings inspired by color studies seem a little slight in comparison, their constellations of rainbow blobs swamped by the white canvases behind them.

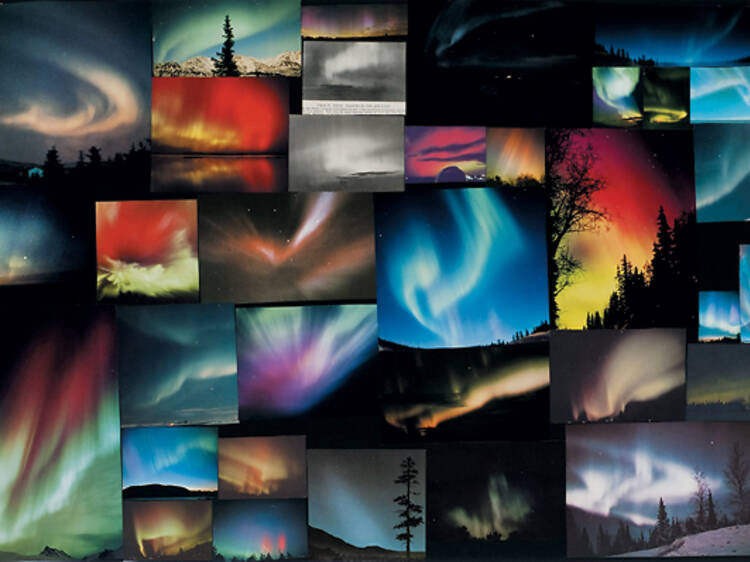

Carrie Gundersdorf tackles the worship of science in found-image collages of astronomical phenomena, which have an affinity for the homely patches and other ephemera Brennan McGaffey designs to commemorate his interventions into our technological environment. More information about McGaffey’s activities would be helpful; the exhibition offers only a vitrine of his cryptic objects.

Except for McGaffey’s and Wolff’s idiosyncratic projects, “New Icon” feels a little too familiar to anyone who’s visited Chicago galleries during the past two years. But these nine artists are bound to find a new audience at LUMA, and their work offers those visitors plenty to contemplate.